General:

Beit El is an Israeli settlement in the Ramallah Governorate, the host of a prolonged legal and political battle between the Palestinians, Israeli settlers, and Israeli court system. Under the Fourth Geneva Convention and Hague Conventions, which prohibit the forced or supported population transfer of one country’s people to occupied territory, Beit El is illegal and illegitimate, although emblematic of the settlement expansion process and Israeli policy. Recent court developments and political reactions reveal a tension between the Israeli court system and the state on matters of settler expansion. As established by the precedent of the Civil Administration and military to anticipate legal controversy, retroactively legalize settlements, and circumvent the High Court of Justice (HCJ) rulings, as observed in Jabel Artis and the Cremisan valley, the likelihood of the occupational authorities to respect the court’s injunction to dismantle the Dreynoff structures in Beit El’s “Ulpana” extension by the July 30th deadline is relatively low and will surely be accompanied by demonstrable reactions and appeasements. In this brief essay, the writer will examine the history and recent developments of Beit El and explore what this analysis suggests about the relationship between the state and the court. All errors of fact and narrative, of course, are the writer’s.

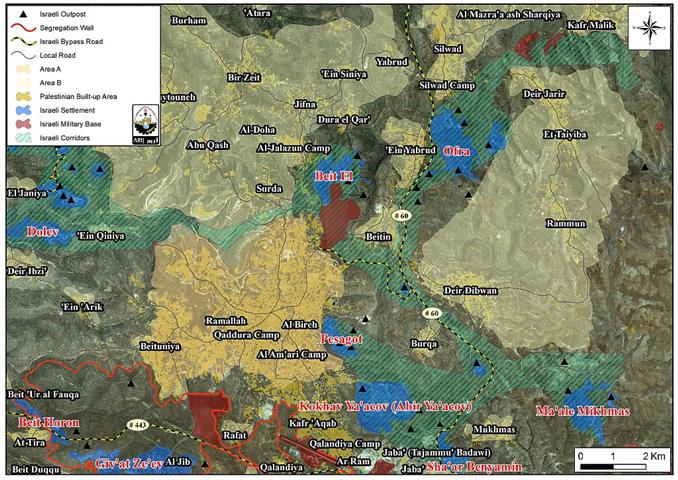

Map 1: Beit El settlement

Timeline:

- 1970 Private Palestinian land of al-Bireh and Dura al Qar was taken by military order for a military base.

- 1977 “IDF” transferred land to Israeli settlers for civilian development, divided into two residential religious communities, A and B, ostensibly out of security necessity to support the military base. The 70’s push to settle Beit El and others, like Elon Moreh and Pithev, was conducted at the height of the Gush Emimem Zionist movement to populate the occupied Palestinian territories, in Zionist terms “Judeah and Samaria.” Additionally, only a small neighborhood of Beit El (Maoz Tzur) was built on the “state land” of the military base, although the author finds the distinction between public domain and private land irrelevant in international law concerning one country’s territorial occupation of another.[1]

- 1978-79 The Israeli Supreme Court, acting in its capacity as the High Court of Justice (HCJ) in a series of rulings (606/78, 610/78, 390/79) approved, in principle, of the State’s establishment of settlements on private land as legal domestically and internationally, on the basis of temporary military necessity, the lease expiring with the military base’s expiration.[2]

- 1997 Beit El achieved local council status and the Beit El A and B along with the illegal structures and neighborhoods between them became one de facto body.

- 1999 Under Benjamin Netanyahu’s support, construction began on the Ulpana neighborhood, “never, ever be evacuated” according to the prime minister.[3] Israeli courts began continuous stop-work orders.

- 2001 After early attempts 90’s attempts to occupy the land by night raid, settlers took the nearby hill of Jabel Artis financed with trailers and infrastructure support from the Israeli Ministry of Housing and Construction and managed by the construction company Amana. Thus, the outpost “Pisgat Ya’acov” was established.

- 2003 To avoid land registration issued, the "IDF" retroactively seized the land of Jabel Artis by military order, ostensibly for another helipad site, still yet to be seen by residents.[4] [5] The Company for the Development of Beit El Yeshiva Complex and Amana began construction on the Ulpana extension.

- 2005 The Israeli government’s Sassoon report listed the Ulpana and Jabel Artis neighborhood as illegal and that the Israeli Housing Ministry provided over a million dollars for its construction.[6]

- 2008 Yesh Din petitioned the HCJ on the behalf of Palestinian landowners against the homes in Ulpana. Settlers continue to build and move on to Jabel Artis, taking advantage of the Civil Administration’s military order at the site.[7]

- 2009 Haaretz daily newspaper published a government database revealing Beit El was largely built on private Palestinian land.[8]

- 2010 Construction began on the “Dreynoff” buildings in the Ulpana neighborhood, despite stop-work injunctions from the court.

Recent Developments:

In the last five years, news has intensified and the issues of Beit El have drawn fierce attention. By October 2011, the High Court of Justice issued its final injunction on the legal proceedings on the Ulpana neighborhood; namely, that the buildings were built illegally and must be demolished by May 1st, 2012. The state admitted the Amana construction company responsible for building the 30 so housing units did not have the legal right to purchase the land,[9] finding the murky land deal to be based on forged documents of deceased owners. Amidst ubiquitous demonstrations, the Ministry of Housing announced tenders for 296 housing units in Beit El in March 2014 to agree for a peaceful eviction.[10] In January 2015, Netanyahu and Civil Administration promised to expand the master plan of Beit El and announcing to compensate the owners by building 300 more housing units in Beit El, spending 70 million NIS to uproot the settlement’s military base.[11]

After the Ulpana ruling, the HCJ three times confirmed the demolition of 24 illegal units in Ulpana constructed without building permits, a master plan, and on private Palestinian land.[12] As the Civil Administration tried to retroactively legalize the apartments, the Palestinian’s legal representative Yesh Din petitioned the High Court, which granted a temporary injunction forbidding the Beit El local council from retroactively authorizing the so-called “Draynoff” structures in the Ulpana neighborhood.[13] Such a petition only came at the price of several repeated litigations, appeals, and the government ignoring the injunctions and deadlines of the High Court.

Days before the scheduled demolition of the Ulpana’s “Draynoff” structures and after armed clashes and arrest of 200 demonstrators on July 27, Prime Minister Netanyahu publically stated his opposition to the demolition and promised to work to prevent the destruction, by “legal means,”[14] an example of which are the retroactive authorizations pushed through the Civil Administration and Beit El local council days before, in defiance of the High Court’s injunction. Such statements, in an effort to preserve Israel’s fragile coalition government and Netanyahu’s dwindling support, complement those issued by the “Defense Minister” M’oshe Ya’alon in charge of the “IDF” forces in Palestine, the Education Minister and legislator Naftali Bennett, (Jewish Home) the Yisrael Party head Avigdor Lieberman, and Agriculture Minister Uri Ariel on the situation of Beit El, always with the caveat that the Supreme Court’s decision must be respected.[15] However, after another HCJ rulings on July 30th against the Civil Administration and Beit El council’s appeal to retroactively legalize for the Dreynoff buildings,[16] Legislator MK Moti Yegev (Jewish Home) declared, “We should send a D9 [armored bulldozer] to level the High Court,”[17] and PM Netanyahu reacted to the July 30th ruling by announcing 300 more housing units in Beit El and 500 housing units in Jersualem.[18] Amidst violent protests, the two Dreynoff buildings were demolished on the 30th. Only a day later, building resumed on top of the ruins, anticipated by the Civil Administration and Netanyahu’s announcement, despite the HCJ’s ban on further construction at the site.[19]

Analysis:

Thus we see the issue of Beit El’s Ulpana neighborhood has grown far beyond its original context; it threatens to rip apart Netanyahu’s coalition and dwindling support, alienates an already-unpopular Supreme Court, and offers a grave, but emblematic instance of usurpation of the rule of law in favor of majority politics. We witness the de facto body of Ulpana existing continuously and in resistance to the de jure convictions of Israel’s highest legal authority. We observe Ulpana has not only been declared illegal in the eyes of international law—a body of precedent the Supreme Court has not yet admitted into its legal discussion despite its relevance—but also found in violation of the laws recognized within Israel itself. Can loopholes to the Supreme Court rulings be found that preserve the prospering settlement enterprise in Beit El? Netanyahu’s administration has done its best to find them. However the Israeli people must ask themselves, at what point does this relationship demise into law fare?

While there are those who view the struggle between the court system, the Beit El settlement community, and the government authorities as a healthy interplay in a political system of diffused and separated power, the author finds the audacious disregard and defiance of the state—the only enforcing body for the Supreme Court decisions—a grave symptom of the breakdown of the rule of law. In a country such as Israel, ostensibly based on principles of separation of powers, democracy, and common law, the separation of executive and judicial functions frees the justice process from political interests and assures a level of detachment necessary for the judging body to navigate arising legal complexities, establish a body of tradition and precedent, and ultimately serve justice. That is the ideal, although by observing the Israeli courts’ complicity in the occupational authorities’ systematic attempt to sabotage the Palestinian state-building enterprise and deny the Palestinian people their rights, one may safely say the Israeli Supreme is not impervious to the ideology and discrimination of the state. In the few cases in which the courts uphold a private Palestinian claim to land seized by settlers—their councils, construction companies, and bureaucratic manifestations—may observers reasonably expect for those rulings to be upheld not only in the hollow shells of their obligation (e.g. demolish these buildings by this date), but in the jurisprudential decision they embody (e.g. this land is private Palestinian land and deserves to be given back to its rightful owners)? By the patterns established to retroactively legalize Jabel Artis and circumvent the Supreme Court ruling in Beituniya, and the Cremisan valley,[20] [21] that expectation is low to nil. As onlookers, we must remain wary of projecting sensibilities of justice on an administrative court decision, nor overstate the implications of such a decision or the guiltlessness of the Israeli court system. However a stand for the rule of law and due process is a responsibility of any institution dedicated to the cause of justice.

A separated-powers system in which law adjudicated by one given political body—the court—is enforced by another—the state and military—has its risks: political leaders may disregard their own courts, and choose not to enforce the injunctions, or (in the words of Ya’alon) “reward hooligans”[22] for their crime, as seen in Beit El recently. When political leaders crown themselves the arbitrators of reparation and reward instigators of violence and injustice, the move is antithetical to the workings of a just and humane state; a policy of political appeasement and legal circumvention ultimately leads to the abuse and the deterioration of the rule of law. As the Beit El situation develops, we continue to be watchful and mindful of the important jurisprudential and human rights forces that are taking place. Let facts be submitted to a candid world.

[1] See Settlement Process: A Study in Illegality, Palestine-Israel Journal (PIJ), Vol.7 Nos. 3 & 4 (2000). See chapter “The High Court of Justice – The Judicial Approval for Israeli Settlement” www.pij.org/details.php?id=256 (accessed August 1, 2015).

[2] See HCJ 606/78 (Suleiman Taufiq Ayub et 11 al. v. Minister of Defense et 2 al), HCJ 610/78 (Jameel Arsam Matu’a et 12 al. v. Minister of Defense et 3 al), HCJ/390 (Izzat Muhammad Mustafa Duweikat et 16 al. vs. Government of Israel, et al) http://www.hamoked.org/files/2010/1670_eng.pdf

[3] Prince-Gibson, E. (2012, May 1). Battle lines in the West Bank’s Ulpana neighborhood with far reaching implications. Jewish Telegraph Agency. Retrieved from www.jta.org/

[4] Rudoren, J. (2012, April 24). Israel Retroactively Legalizes 3 West Bank Settlements. New York Times, p. A9. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/

[5] Levinson, C. (2012, June 22). Beit El land deal was based on forged documents, probe finds. Haaretz. Retrieved from www.haaretz.com/

[6] Yesh Din Petition, Order Nisi, High Court of Justice (9060/08) paragraphs 31-33. Retrieved from http://www.yesh-din.org/userfiles/file/Petitions/Jabel%20Artis/Jabel%20Artis%20-%20Petition%20Summary%20ENG.pdf

[7] Harel, A. and Issacharoff, A. (2008, Sept. 4). State admits outpost built on private Arab land. Retrieved from www.haaretz.com/

[8] Blau, U. (2009, Jan 1). Secret Israeli report reveals full extent of illegal settlements. Haaretz. Retrieved from www.haaretz.com/

[9] Prince-Gibson, E. (2012, May 1). Battle lines in West Bank Ulpana neighborhood with far reaching implications. Jewish Telegraph Agency. Retrieved from www.jta.org/

[10] Applied Research Institute-Jerusalem. (2014, April 1). Is Israel Seeking Peace with the Palestinians? New Israeli tenders targeting eight settlements in the occupied Palestinian territory. Poica, Eye on Palestine. Retrieved from www.poica.org/

[11] Times of Israel Staff. (2015, January 4). PM transfers NIS 70m to move "IDF" base, expand settlement. Times of Israel. Retrieved from www.timesofisrael.com/

[12] Lazaroff, T. (2015, July 26). High Court issues injunction against authorization of the Beit El homes. Jerusalem Post. Retrieved from www.jpost.com/

[13] Gurvitz, Y. (2015, July 29). For Palestinian land, the High Court contradicts itself. Isolated Incident, Yesh Din. Retrieved from http://blog.yesh-din.org/

[14] News Brief. (2015, July 28). In West Bank Settlement, Jewish protesters clash with police. Jewish Telegraph Agency. Retrieved from www.jta.org/

[15] Lazaroff, T. (2015, July 28). Netanyahu after settler clashes with police: ‘We oppose demolition of Beit El homes.’ Jerusalem Post Retrieved from www.jpost.com/

[16] JPost.com Staff. (2015, July 29). Israel’s High Court orders demolition of homes in West Bank settlement. Jerusalem Post. Retrieved from www.jpost.com/

[17] Tuchfeld, M. (2015, July 31). The demolition that sidelined Pollard. Israel Hayom. Retrieved from www.israelhayom.com/

[18] Ibid.

[19] Forsher, E. (2015, July 31). Beit El resumes atop ruins of razed structures. Israel Hayom. Retrieved from www.israelhayom.com/

[20] Land Research Center (LRC). (2014 Dec. 12). Extending the validity of a land grab in Ramallah. Poica, Eye on Palestine. Retrieved from www.poica.org/

[21] Laban, Rafat. (2015 July 8). The Israeli Supreme Court Gives the Green Light to Begin Building the Separation Wall in the Cremisan Valley. Society of St. Yves. Retrieved from www.saintyves.org/

[22] Verter, Y. (2015, July 31). After Beit El, settlers learn violent threats pay off. Haaretz. Retrieved from www.haaretz.com/

Prepared by:

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem