Prelude,

Through the various administrators and occupiers who ruled upon the Palestinian land, the Bedouins, largely those in the Naqab area, intensely collided with whatever ruling the administrator sought to apply on their way of life; particularly, for what concerned land ownership.

In 1858, the Ottoman Khilafah decreed a law for a land ownership regulating process before the lord of the land. It required any individual who claims property to a private land to officially register it to their names in the official records of the administrative government in charge. The Naqab Bedouins refused to deal with the Ottoman decree to authenticate their land holdings, as for it they would be subject to foreign rule and answer to an alien environment, different to what they are accustomed to in their nomadic way of life. The bulk of the Bedouins land in the Naqab were grazing pastures – categorized by the ruling Ottoman Khilafah as “Mawat”[1] – and they would be compelled to pay taxes for the land and send off their men to be in service of the Ottoman Khilafah army.

At the end of the Ottoman Khilafah ruling era, Palestine went under the British Mandate rule. In 1921, the British Mandate government asked Palestine mandate’s residents to register their claims of landownership, including the Naqab Bedouins. They refused to conform, thus their claim of land ownership remained officially unregistered. Still, whatever piece of “Mawat” land that was cultivated by any of the Bedouins was re-categorized to what was known as “Miri” land and was awarded a landownership certificate accordingly.

After the 1948 war and the founding of the State of Israel (May 15, 1948), the legal system of the newly created state deprived the Bedouin of any claim to the “Mawat” land. The Bedouin land was expropriated, mostly in accordance with the Land Acquisition Law of 1953, which basically deemed any land not claimed by the owner as of April 1952 likely to be registered as state land.

Indeed, most of the Bedouin population were either expelled or forced to flee or to the surrounding countries, as Jordan, Egypt, Gaza and the West Bank (hence, most of the West Bank (oPt) Bedouins originate from the Naqab), or pushed and confined to the northeastern corner of the Naqab area. Accordingly, the majority of the Bedouins were banned from returning to their land by the newly established Israeli state military ordinances.

The term “forced”, when used in reference to the crime of deportation, is not to be limited to physical force but includes the threat of force or coercion, such as that caused by fear of violence, duress, detention, psychological oppression or abuse of power, or by taking advantage of a coercive environment.[2]

The Israeli Land confiscation violates art. 46of The Hague Regulations (1907), which prohibits the confiscation of private land and property; hence, the occupying power must manage public property as a usufruct. The use of public lands by Israel is not consistent with the concept of usufruct. Nonetheless, Israel later on established two “developed Jewish towns”: Dimona (1953) and Arad (1962) both north of the Naqab area.

Cracking on the oPt- West Bank Bedouins

The Israeli government dismisses the unanimously concurred fact that its presence in oPt is indisputable occupation, but rather considers itself as the natural inheritor of the previous administrators of the land of Palestine (Jordan, British, and Ottoman). In the West Bank, Israel has rounded its Cumulative Land Grab on some 2300 km² (+/- 41%) of the West Bank area (5661 km²) under “State Land” claims that, through instrumental military orders that ensure its grip on the land, among which:

- State Land (Military Order No. 59/ 1967),

- Mined Area (Military Order No. 151/ 1967),

- Training & Closed Military Area (Military Order No. 271/ 1968 & No. 378/ 1970),

- Nature “Preservation” Reserve Area (Military Order No. 363/ 1969)

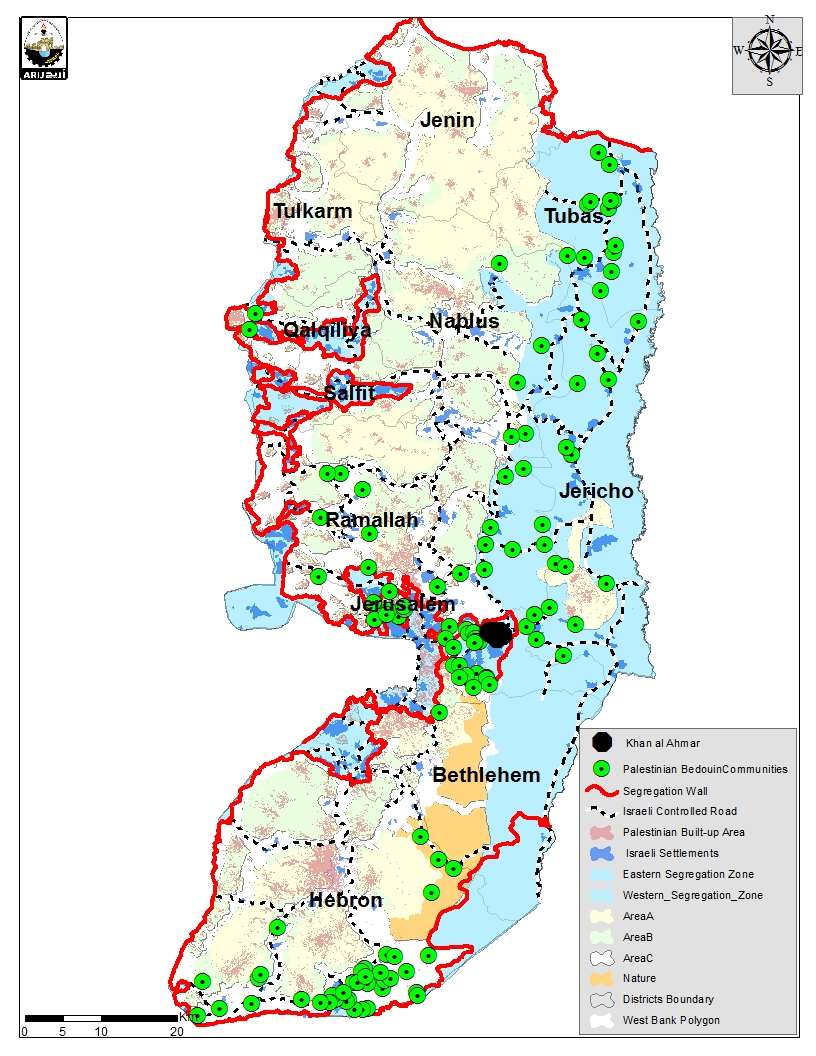

Map 1: the locations of training zones and closed military areas in the Occupied West Bank

Map 1: the locations of training zones and closed military areas in the Occupied West Bank

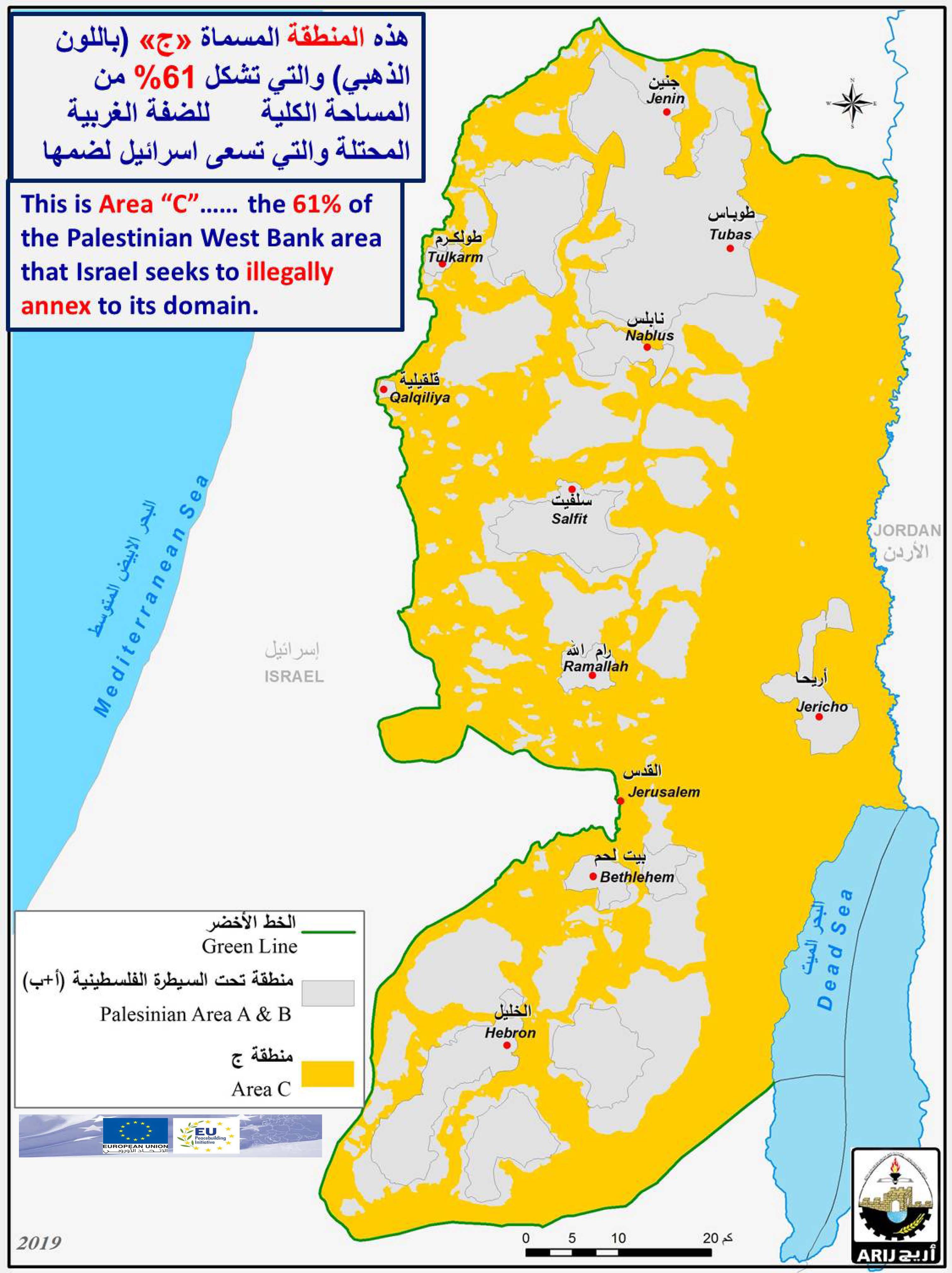

The Israeli “unilateral” claim over state land spread across the area, which came to be known as “Area C” under the Oslo II Accord classification[3], which amounts to 61% of the occupied West Bank territory.

Map 2: the “state land” areas in the West Bank according to the Israeli classification

However, prior to Oslo, Israel had tailored a legal system that allowed it to apply the Israeli laws exclusively and discriminately on one segment of the population (the Jews) who coercively inhabited the oPt and not to the other (the Palestinians). In doing so, the Israeli occupation was able to maneuver the imposition of foreign (Israeli) legal system in the oPt in order to protect Israeli settlers. On the other hand, Israel used its own military laws, in addition to bygone laws from the previous administrators of Palestine (the Jordanian, the British and the Ottoman) to govern the non-Jewish residents (the Palestinians; including the Bedouins).

The origin of the apartheid system stemmed from general acts, particularly the construction procedures for those inhabiting areas “C”, differentiating between Palestinians – including the Bedouins tribes and Israeli settlers.[4] The former are bound by limitations set by the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA)[5] , while the latter enjoy limitless support to every aspect of their illegal existence in the territory.

Bedouins in the West Bank fall under coercive conditions no less dehumanizing than those to the Bedouins in the Naqab area. The ICA regards and treats West Bank Bedouins as enemies of the State and denies them the basic services and rights as residents of the land, under the pretext that the area of their residency falls out of any town-planning scheme. Thus, their communities are deprived of basic public services: of electricity, water, roads, education, health services, etc. however, the ICA has no problem when it comes to facilitating the Israeli settlements services and the outposts, including providing security protection for the Israeli settlers.

Israel maintains full command over the planning and construction, and all what is related to the procedural steps, policies, and materializing on the ground. This situation constitutes a direct violation of the provisions of Article 43 of The Hague Regulations and Article 64 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, in which the enactment of new legislation or the amendment of legislation in force in the occupied territory is prohibited, unless they constitute a threat to its security or an obstacle in this matter.

About the applicability of the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 to the 1967 occupied Palestinian territory.

Israel adopted the Fourth Geneva Convention on the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War and signed it in 1951. However, when Israel occupied the 1967 territories it issued a series of military orders and proclamations for regulation purposes concerning lands and properties belonging to other standing countries (the Jordanians, the British and the Ottoman), which had fallen under its control.

Accordingly, Israel considered the land under its control as a result of the 1967 war an occupied territory to which international law applies, including the provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949.

This was reflected in the texts in three proclamations issued by the Israeli military commander, the third of which indicated under article 35 that the military courts will apply the provisions and rules of the Fourth Geneva Convention relating to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War of 1949 with regard to all matters on judicial procedures.

It was a straightforward acknowledgment that in the event of a contradiction between the military order and the Fourth Geneva Convention, the provisions of latter shall prevail.

Subsequently, in his representative capacity of Israel, the Israeli military commander of the occupied territory issued the second military proclamation, in which he assumed absolute control of all legislative, judicial and executive powers.

However, soon after that Israel revealed its intentions towards the occupied territories of 1967. Hence, Israel sought to revoke article 35 of the third proclamation, and give primacy to Israeli military law over the provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention. As Israel recanted adherence of international agreements concerning its status as an occupation force of the West Bank and Gaza, it consequently brushed-off the applicability of the Fourth Geneva Convention of August 1949, along with The Hague conventions of 1897 and 1907. Israel’s position was then and to this day widely criticized by states party that soon after, reaffirmed how international humanitarian law shall apply to the occupied Palestinian territory, including East Jerusalem.

However, the fact that the West Bank Bedouins fall under occupied territory puts them in a special category as they are protected persons in accordance to international humanitarian and human rights law, which also affirm their right to housing and the right to lead their own way of life.

The practices of oppression against the Palestinian Bedouins are incessant acts that evident in their strategies of dispossession. Israel systematically deny the indigenous rights to the land, it demolishes their houses (particularly targeting the Bedouins tribes in the Jordan valley, southern Hebron and the east prairies’ of East Jerusalem), and forced displacement (some 46 Palestinian Bedouin/herding communities are at risk of imminent displacement by ICA to newly set locations).

The number of Bedouin communities in the West Bank is of 126, 33 of which are within Jerusalem Governorate boundaries and 21 of which settled the eastern prairie in Jerusalem after they were displaced in the early 1950s from the Naqab desert area.

Map 3: The distribution of Bedouin communities in the occupied West Bank

The area where they settled (the eastern prairie of Jerusalem) was identified later on in the Israeli Municipality development plans as “E1”. The Bedouins there became a constant target of Israel, by demolishing their habitation to displace them again under the pretext of “lack of documented land claim”, one of many alleged reasons the Israeli occupation uses to hunt Palestinians out of their land. As the Palestinian Bedouins fought the Israeli plans every step of the way, Israel attempted to dodge the discrimination card and produced proposals to relocate them, none of which were consistent with the Bedouins nomadic practices.

Even more, a protection committee for Bedouin communities at the Jerusalem eastern prairie was formed to stand for the interests of the Bedouins based on a prioritized agenda. It revolved around three main objectives; (a) the right of Bedouins return to their original habitation in the Naqab area, (b) if they are not allowed to return, that they remain in their current inhabiting area, and (c) if their relocation plot became inevitable, that it would be to a location of their approval.

“Under international law, such as Article 13(2) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), all refugees are entitled to the right to return to their ancestral and tribal lands.”

The committee’s function was confined to political representation in order, to realize the basic rights they seek to fulfill on the ground. However, the impasses of their situation epitomize in: (a) the fact that Bedouins are not officially recognized as a cluster, (b) they have no official representation, not alone a spokesperson on their behalf. If every Bedouin tribe act independently, the Israeli side can exploit this weakness, (c) the tangling of consolations and consultations parties involved and the absence of the coordination efforts among the involved parties.

In any case, Israel made sure that the Bedouins were never capable to take a decision on their status in a collective manner, but rather in separate deals conducted each to their own interests and merits.

The following lines of this paper are meant to explore how the Bedouins (both living in Israel and the occupied territory) face an ethnic war of displacement with unhidden intention to favor one group (the Jewish population) over the other indigenous one– the Bedouins.

Israel as a neo-colonial ethnocentric state

Israel deems its existence in the West Bank as part of a power struggle with the Palestinians, particularly over ownership rights to the land, perceiving itself as the natural inheritor of what is labeled as “State” land property. On February 6, 2017, the Israeli Knesset passed a law for the regulation of settlements in Judea and Samaria (the West Bank), which is intended to define the land on which Israeli settlements were built in “good faith” or “with the consent of the state.” The law inscribes to register the land that has no ownership claim over it to the name of an Israeli government official.

Concurrently, the Israeli 2018 Basic Law (updated in 2021), views the Jewish settlements as a “national” value and entrenches the mentioned “regulation law”. It constitutionalizes the settlements and upholds them as national assets. Even more, the law extends the right to expropriate privately owned land (meaning Palestinian land) until a political arrangement is concluded. Meanwhile, people with proven land ownership claims affected by such expropriation will be financially compensated or if possible be presented with a substitute land.

Furthermore, as of the publication date of the law, all pending administrative orders related to evacuation or demolition of structures in Israeli settlements (particularly 16 of them) shall be suspended.

The law did not extended the suspension to Palestinian communities, a disturbing reality that really foil the myth that Israel stand to be the only democracy in the Middle East.

Nevertheless, Israel has long acted outside of the international law and the international consensus, particularly in relation to Israeli settlements, which have been condemned by dozens of United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) and United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolutions, the last of which was Resolution 2334.

The UNSC Resolution explicitly refuted any Israeli policy and procedure aiming at manipulating the demographic balance and geographic shape of the oPt, especially in East Jerusalem. In any case, that did not deter the Israeli occupation from constructing 199 Israeli settlements that accommodate more than 913 thousand Israeli settlers in violation of international law and in contradiction with UN resolutions[6].

As an occupying power, Israel is under the responsibility of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which declares in article 49, “the Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.”

Indeed, Israel surely did not act in accordance with international law and the Geneva Conventions, but rather actively promoted and nurtured its own “Jewish” population transfer to the occupied territory, ultimately not acting in good faith and validating the institution of “facts on the ground”.

In line of that, Israel demolished some 25,000 Palestinian houses and structures in the oPt area, more than 2,200 (of which 194 Donor funded) in the last decade, displacing in the process more than 3,800 Palestinians.

The Fourth Geneva Convention, in article 53, states, “Any destruction by the Occupying Power of real or personal property belonging individually or collectively to private persons, or to the State, or to other public authorities, or to social or cooperative organizations, is prohibited, except where such destruction is rendered absolutely necessary by military operations”.

The Bedouins in the West Bank are no different in status from the Bedouins with Israeli citizenship when land ownership and territorial claims in issue; Israel discriminates against them both just the same. While the Bedouins land in the West Bank are targeted by the Israeli tailored laws to deprive them from ownership, the Bedouins with Israeli citizenship are discriminated against by Israel’s ‘regularization’ policies, which are driven by the Israeli state ethnocratic policy that was emphasized and manifested in amendment (# 4) of the “Negev Development Authority law”. This law allows for legal tools for the allocation of “Jewish” families in the Negev in independent private settlements.[7] In such setting, the Israeli discrimination explicitly unfolds as “Jewish” citizens are allowed to live in single-family farms, kibbutz or communes, while Negev Bedouins are offered the sole option of relocating to failing government-approved townships.[8] To further illustrate the dispossessing ownership laws, it is necessary to mention the April 2017 Kaminitz Law, which was ratified to increase the demolitions of the Negev Bedouins properties without necessarily passing through a judicial review.[9] The ratification of this law demonstrates the same permit regime policy in both Israel and oPt, which advocates for demolition processes to vulnerable and marginalized communities.[10] The Kaminitz Law is part of the larger five-year economic development plan in the Negev known as the Prawer plan, approved in 2011. The Prawer plan aims to relocate a number between 30,000 to 40,000 Bedouins from their unrecognized villages to government townships. The plan has been designed to address the legal and citizenship status of Bedouins; however, it ratified a 50% transfer of Bedouin land to state land without compensation and by employing forced displacement through demolitions. The regularization is implemented by the “Yoav” Unit, a special police patrol created one year later to implement the Prawer plan. The “Yoav” Unit specifically targets the displacement of Bedouin unrecognized villages.[11] The state of Israel through bodies such as the Be’er el-Sebe (Naqab) Court or Bedouin Authority has used a systematic ´stick and carrot´ policy towards Bedouin ownership claims, one based on a permit regime.[12] The Prawer plan is criticized as a tool for the Judaization of the Negev. Those Bedouins who accept the relocation are then allowed building permits.

Israel violates terms of equality and human rights dignity

Israel’s democracy is a monopoly for Jews, not for the Palestinians and certainly not for the Bedouins, a fact that is exemplified in the existence and operating of two different legal systems in the oPt. The first is tailored to serve the Jewish population in every letter of the words it is inscribed in; while the other is meant to discriminate against the Palestinians, the Bedouins and any other non-Jewish in every possible way, which undoubtedly violates numerous international treaties concerned with the very basic principle of equality and ban of all forms of discrimination.

However, that did not stop Israel from taking part and become a signatory to the “International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1965)”, under which article 1 clearly states to the signatory parties that:

“In this Convention, the term ‘racial discrimination’ shall mean any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, color, descent, or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.”[13]

To that end, Israel signed and ratified the “International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights of (1966)”, even if it calls upon the signatory parties under article 2 to commit: “to respect and to ensure to all individuals within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction the rights recognized in the present Covenant, without distinction of any kind, such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”[14]

Yet, the State of Israel has managed to be at odds with the aforementioned principles every step of the way, as it insists to instrument the system of discrimination within its legal structure based on national-ethnic origin, which is distinctively distinguished when the application of the “Law of Return” is in question[15].

Case in point, the Israeli military legislator denies residency to in Israeli West Bank settlements for Israeli citizen and/or resident of Israel or holding permits to enter Israel, in a more specific manner for “none Jews” to whom the “law of return” do not apply. Hence, if the Bedouins residing within the East Jerusalem prairies are to remain in the current area, it will be difficult for Israel to remove them later on once the area is annexed to Israel’s proper under the “Greater Jerusalem” plan.

This shows why Israel is keen to eradicate the Bedouins in the eastern prairies of Jerusalem out before it executes the “Greater Jerusalem”[16] plan, which intended to incorporate the Ma’ale Adumim settlements bloc (73 km2 in area) including the Bedouins tribe who live there.

Again, such an act of discrimination against Palestinians and the Bedouins in particular is an evident breach of article 2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, no matter how deceitful Israel attempts to rebut it.

The outcomes of Israel’s acts and practices against non-Jewish residents are undeniable proof of its segregation system that stands nothing shorter than explicit grounds and evidence that Israel national-ethnic origin based system makes it discriminatory State.

Upon the coercive exodus of the Bedouin tribes from the Naqab dessert following the 1948 war, Al-Jahaleen tribe went to relocate to the West Bank at the eastern prairies of Jerusalem, the area where Ma’ale Adumim settlement would be constructed later on. Following the occupation of the West Bank after the 1967 war, the Israeli Army restricted land use for the Palestinians; including the Bedouin tribes in various locations, the Al-Jahaleen tribe was one of whom that was denied access to grazing grounds and later pushed to move to a spot along the road lane between Jerusalem and Jericho. In 1979, the Israeli settlement council officially recognized Ma’ale Adumim as a settlement; taking no account of the reality that Al-Jahaleen Bedouins resides the area.

The designated initial development area was set at 2930 Dunums out of a spread area in excess of 37,500 Dunums expropriated from surrounding Palestinian communities in 1975 and 1977 under Israeli Cabinet Resolution No.835 (HT/20, 23, 51)[17] and based on:

- “State Land” expropriation order No. 59/1967[18],

- “Absentee Property” order No. 58/1967[19],

- “Land Law Order (acquisition for public Purposes)” order No. 321/1969[20],

The abominate creation of Ma’ale Adumim had a destructive effect on Al-Jahaleen tribe, who faced various waves of demolitions committed against their community at the orders of Israeli authority.

In 1994, the Israeli Civil Administration forcibly relocated dozens of Al-Jahaleen families from a location that was allocated to them upon the construction of Ma’ale Adumim site to the outskirts of Abu Dis, which is also declared as “State Land” under order No. 59/1967. Two more expulsion waves were implemented against Al-Jahaleen tribe in 1997 and 1998 for the same purpose.

The “E1” Plan,

During the two decades to follow, Israel would confiscate an additional 12,733 Dunums under the pretext of “State land” (order concerning State Land No. 59/1967). This new area would come to be known as “E1” where Israel plans to build an additional neighborhood to link Ma’ale Adumim geographically with East Jerusalem.

Israel had a plan to make the Ma’ale Adumim settlement bloc (73 km2, an area roughly equivalent to East Jerusalem area) part of its so-called capital Jerusalem. Hence, the Israeli plan was to remove all non-Jewish elements out of the settlement bloc area, which Israel plans to enclose with the segregation wall, in order to pave the way to link the entire bloc with East Jerusalem. The 1991 “E1” plan, which covers across a spread of 12733 Dunums, was devised to such end, regardless of the threat it brings to the lives of the 21 Bedouin communities who were there at the time.

Map 4: The bedioun communities located within the Ma’ale Adumim Settlement Bloc and the E1 Plan

Case Study: Khan al-Ahmar,

The “ICA” plan was to relocate whoever remained of the Bedouins (Khan al-Ahmar) within the Ma’ale Adumim settlement bloc to alternative sites: the first on the outskirts of Abu Dis, next to the Jerusalem municipal garbage dumpsite on the side of the segregation wall that will not be part of the “greater Jerusalem” plan. The other alternative was suggested in north of Jericho, in An-Nueimeh area.

The Israeli discriminatory policy on land development and its impact on the displaced minorities (in Israel and the oPt alike) was highlighted by the independent UN Special Rapporteur on adequate housing, Professor Raquel Rolnik. She stated that Israel’s strategy to relocate the Bedouins in the Naqab (Negev) area while promoting for years exclusive “Jewish” settlements in the oPt (West Bank; including East Jerusalem) – “are the new frontiers of dispassion of traditional inhabitants, and the implementation of a strategy of Judaization and control of the territory.”[21]

Ultimately, it is evident that Israel has employed a series of instruments and tailored laws to displace the Palestinian Bedouins from their habitat on both sides of the Green Line. Some of the measures used by Israel included:

- Houses Demolitions, for various pretexts:

- a) Demolitions as a punitive (collective) punishment,[22]

- b) Administrative demolitions,[23]

- c) Military/ Security purposes,[24]

- Land Confiscation for claims of:

- a) Public needs (roads, infrastructure, etc.), under Israeli military order 321/1969[25]

- b) Nature Reserves & Forests, under Israeli military order 363/1969[26]

- c) Establish Parks areas under Israeli military order 373/1970[27]

- d) State Land: for expansion of settlements and outposts and other purposes, under Israeli military orders No. 58 & 59/1967[28]

- e) Establish Military related areas, under Israeli military order 151/1967[29]

- f) Antiquities areas under Israeli military order 1166/1986[30]

Concluding remarks,

Acts of forcible displacement underlying the crime of persecution punishable under Article 5(h) of the (Rome) Statute are not limited to displacements across a national border. The prohibition against forcible displacements aims at safeguarding the right and aspiration of individuals to live in their communities and homes without outside interference. The forced character of displacement and the forced uprooting of the inhabitants of a territory entails the criminal responsibility of the perpetrator, not the destination to which these inhabitants are sent.[31]

The International humanitarian law, in addition to art. 49 and art. 147 of the Fourth Geneva and its related Conventions, respectively, categorically prohibit the occupying power to transfer any part of its population to the occupied territory, except in rare cases when security and/or military situations (war) arise; and unlawful and unjustified destruction of their properties.

Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention states: “The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.” It also prohibits the “individual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory”.

The Fourth Geneva Convention, Article 147, stipulates that “extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly” is a “grave breach” of the Convention.

It should be underlined that the legal status of the Bedouins in Israel -the Naqab – differs from the Bedouins residing within the vicinity of Jerusalem and the West Bank. The latter are considered residents under occupation, and therefore they are protected according to international humanitarian law, its conventions and protocols, and the human rights conventions that emphasize the right to housing and the right to respect the privacy and way of life apply to them – the indigenous.

On the other hand, the Bedouins in the Naqab area (Israel)on the account they hold Israeli citizenship, are not considered protected citizens, Israeli law and human rights law still apply to them, but not international humanitarian law. Nonetheless, the Israeli law too prohibits infringement to housing rights and discrimination in that regard, as was confirmed by several committees of the United Nations when the issue of Bedouins in the Naqab was in discussion, affirming that the transfer of Bedouins from their traditional habitat has repercussions and impacts on their human rights.

Ultimately, it is safe to say that Israel sees the Bedouins on both sides of the Green Line from the same perspective: illegal residents that should be relocated and chased away from their natural habitat, regardless of their disparity and legal status. In fact, Israel uses the Bedouins on both sides to experiment different policies and tactics by means of its civilian laws beyond the Green Line or military laws in the oPt.

******************************************************************

[1] Land during the time of the Ottoman Khilafah were named in five categories:

- Mulk (land under private ownership),

- Miri (state-owned land that could be cultivated for a one-time fee),

- Mauqufa (land in a religious trust or Islamic endowment),

- Metruka (uncultivated land), also “communal” land, mainly reserved for public or communal use — such as pastures and roads use of the adjoining villages.

- Mawat (wasteland unsuitable for cultivation).

[2] International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of Former Yugoslavia since 1991: IN THE APPEALS CHAMBER: JUDGEMENT of 22 March 2006, PROSECUTOR v. MILOMIR STAKI, para. 281

[3] Under the Oslo II Accord of 1995, the West Bank was classified into three various levels of control:

- Area “A”, Palestinians have full control of territory-(security and administration)-(17.5%),

- Area “B”, Palestinians have administrative control of territory (health, education, etc.) but security wise it remains under Israeli control-(21.5%),

- Area “C”, Israel remain of full control of territory-(security and administration)-(61%),

[4] An Israeli settlement, are colonies built illegally under international law; exclusively for Israeli Jewish settlers after the 1967 war and the occupation of the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai Peninsula.

[5] In 1981, the Israeli cabinet established the “Israeli Civil Administration”- (ICA), as a governing body over the territory it occupied during the 1967 war in order to manage civilian activities on its behalf, in order to carry out bureaucratic functions such as planning, transportation, health, education, etc.

[6] • United Nations General Assembly Resolution No. 2851 of 1971: The resolution condemned the Israeli settlement in the occupied territories.

- Security Council Resolution No. 446 of 1979: The resolution affirmed that the host alternative to the Israeli government is illegitimate.

- Security Council Resolution No. 452 of 1979: The resolution stipulates halting settlements, even in Jerusalem, and not recognizing its annexation.

- Security Council Resolution No. 465 of 1980: The resolution called for dismantling.

[7] “Negev Individual Settlements” – Negev Development Authority Law – Amendment No. 4.” Adalah Database.

Accessible online at https://www.adalah.org/en/law/view/500

[8] Noach, H. (2010). “International Human Rights Day 2010: A Report on the Right to Housing; Housing

Demolitions of Bedouin Arabs in the Negev-Naqab,” Negev Coexistence Forum for Civic Equality in association

with the Recognition Forum

[9] “Adalah attorney at UN: Israel moves to evict dozens of Bedouin families to expand Israeli town of Dimona,”

Adalah. Accessible online at https://www.adalah.org/en/content/view/9822

[10] Berger, D. N. (ed.) “Middle East”, in The Indigenous World 2019, pp. 376-378

[11] Ibid., p. 382

[12] Al-Qadi, N. (2018) “The Israeli Permit Regime: Realities and Challenges,” The Applied Research Institute-

Jerusalem (ARIJ). Available from https://www.arij.org/files/arijadmin/2018/permits1.pdf

[13] It should be noted that according to Article 3 of the Convention, “States Parties particularly condemn racial segregation and apartheid and undertake to prevent, prohibit and eradicate all practices of this nature in territories under their jurisdiction.” There are those who claim that the dual legal system upheld by Israel in the West Bank also contravenes this obligation, because at least elements of apartheid and even of colonialism – which are prohibited under international law – can be identified in it. One notable example is the 2007 report of the United Nation’s Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967: John Dugard, Human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories, UN Human Rights Council, 29 January 2007, A/HRC/4/17, p. 3, 23: http://unispal.un.org/UNISPAL.NSF/0/B59FE224D4A4587D8525728B00697DAA.

The prohibition on apartheid is enshrined in the International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid (1973) and in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998), although the definition of “apartheid” is somewhat different in each of those documents. Israel is not party to those conventions, but the prohibition on apartheid is considered today customary international norm, binding on all states. This report will not address the question of if and to what extent the Israeli rule over the West Bank meets the legal definition of “apartheid,” because in our opinion, the debate over this question shifts the focus from the essence of the issue that is extensively discussed in this report.

[14] PART II Article 2 of the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,

[15] Article 6b(a) of the Defense (Emergency) Regulations (Judea and Samaria – Adjudication of Offenses and Legal Assistance), 5727-1967.

[16]Greater Jerusalem’ gained currency as a concept during the late 1970s/early 1980s, when the Israeli government expanded the area of settlement construction outside the Israeli defined Jerusalem municipal boundary in order to create settlement continuity around Jerusalem to cut the territorial continuity of East Jerusalem with the rest of the West Bank. This was to increase the Jewish population around Jerusalem and impose Jewish demographic supremacy that would strengthen the Israeli hold on the city. The new settlements were concentrated in three main blocs: the Giv’at Ze’ev bloc in northern Jerusalem, Ma’ale Adumim in eastern Jerusalem and Gush Etzion southwest of Jerusalem.

[17] Cabinet Resolutions:

835 (HT/20) ‐ 26 July 1977: Acknowledging Ma’ale Adumim as a permanent settlement. “We hereby decide: The cabinet and WZO joint settling committee is acknowledging the settlements of Elon More, Ofra, and Ma’ale Adumim as settlements for all intent and purpose, ordering the settling bodies to handle them as is customary.”

HT/23 ‐ 2 August 1977- Responsibility for Handling Ma’ale Adumim. “In consequence of Resolution HT/20 of the cabinet and WZO joint settling committee dated 26 July 1977, we hereby decide to assign: “1. The MCH with handling Ma’ale Adumim. “2. The WZO‐SD with handling Ofra.”

HT/51 ‐ 5 July 1978 “We hereby decide: “1. To approve the establishment of Ma’ale Adumim on the site suggested as Mark A of the Greater Jerusalem development plan, which will include the physical deployment of economic and social elements. “2. This resolution is reserved with the cabinet secretariat

[18] Order Concerning State Property (Judea & Samaria) (No. 59-1967)

The order establishes the Israeli Military-appointed position of ‘Custodian of Government Property’ to take control of land owned by the Jordanian Government. Also, allows the ‘Custodian of Absentee Property’ to appropriate land from individuals or groups by declaring it ‘Public Land’ or ‘State Land’, the latter defines as land that was owned or managed by, or had a partner who was an enemy body or citizen of an enemy country during or after the 1967 war (amended by M.O.1091).

[19] Order No. 58 Order on Abandoned Properties (Private Property) (1967) – gives control of absentee land to Israeli military. Defines absentee as someone who left Israel before, during, or after the 1967 war. Allows Israeli Military to keep property even if the property was taken by mistake due to a misjudgment (that it was abandoned for example).

[20] “Land Law Order (acquisition for public Purposes) (Judea & Samaria) (# 321[1]) 5729-1969– gave Israeli Military right to confiscate Palestinian land in name of ‘Public Service’ (left undefined), and without compensation. This acquisition procedure was adapted by the Israeli Army after a Jordanian law (law#2: Expropriation for public purposes of 1953) which entitled government Authority to appropriate land for public benefit only after a declaration of such intention is published in the official Gazette with specified details. The order does not change the essential provisions of the Jordanian expropriation law, but transfers the powers it granted to Jordanian governmental bodies to officials in the Israeli military government.

[21] https://news.un.org/en/story/2012/02/403062-un-human-rights-expert-calls-urgent-revision-israeli-housing-policies

[22] Houses demolished as retribution against any act of resistance. It directly affects other members of the family.

[23] Houses demolished for lack of authorized licensing from the Israeli Civil Administration (in Area “C”) and by the Israeli municipality of Jerusalem in East Jerusalem.

[24] Houses demolished for claimed security purposes by the Israeli Army for reasons that include but not limited to military operations.

[25] Israeli Military Order No. 321: Order Concerning the Land (Acquisition for a Public Purpose) Law (Judea and Samaria) (No. 321), 5729 – 1969. The order does not change the essential provisions of the Jordanian expropriation law, but transfers the powers it granted to Jordanian governmental bodies to officials in the Israeli military government.

[26] Israeli Military Order No. 363: Order Regarding Nature Protection (Judea and Samaria) (No. 363), 5730 – 1969: This military order entitles Israel to declare vast areas of the West Bank as “nature reserves” on which severe restrictions are imposed with regards to construction and grazing. Under the guise of the protection of the environment, the Israeli authorities make extensive use of this mechanism to seize additional lands from their Palestinian owners.

[27] Israeli Military Order No. 373: Order Concerning Parks (Judea and Samaria) 1970: states that once an area in the West Bank has been declared a park, it is the duty of the commander of the area to appoint an authority to manage its affairs (section 4). Such as determining rules of conduct in parks, carrying out various construction activities, setting entrance fees, and appointing inspectors (sections 5-7). Order 373 does not stipulate who can be appointed as a managing authority. On the basis of the military order 373 regarding national parks, residents were denied the right to plant olive trees and to carry out repairs and expansions of their agricultural terraces and residential homes without permission from the Nature and Parks Authority. Residents’ applications for permits were not approved.

[28] Israeli Military Order No. 59 of 1967 establishes the Israeli Military-appointed position of ‘Custodian of Government Property’ to take over land owned by the Jordanian Government. Also, allows the ‘Custodian of Government Property’ to appropriate land from individuals or groups by declaring it ‘Public Land’ or ‘State Land’, the latter which it defines as land that was owned or managed by, or had a partner who was an enemy body or citizen of an enemy country during the 1967 war (amended by M.O.1091).

Order No. 58 Order on Abandoned Properties (Private Property) (1967) – gives control of absentee land to Israeli military. Defines absentee as someone who left Israel before, during, or after the 1967 war. Allows Israeli Military to keep property even if the property was taken by mistake due to a misjudgment (that it was abandoned for example).

[29] Israeli Military Order No. 151 of 1 November 1967 Order Concerning Closed Areas (Jordan Valley): This is an example of a declaration of ‘closed areas’. MO 151 declares the Jordan Valley a ‘closed area’ and stipulates that anyone wishing to enter or exit the area must obtain a permit. As noted in Subsection 5.3.1 above, the Jordan Valley was targeted for colonisation and permanent retention under the Allon Plan. An amendment to this Military Order, MO 388 of 1 June 1970, provides a redrawn map of the ‘closed area’. Two other amendments to this Military Order were added later.

[30] Israeli Military Order No. 1166 of 1986: Order concerning antiquities in the West Bank. This order amended the Jordanian Temporary Law No. 51 on Antiquities of 1966 and authorized the Israeli antiquities staff officer for the West Bank to exercise most of the regulations contained in the Jordanian law.

[31] International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991: IN THE APPEALS CHAMBER: JUDGEMENT of 17 September 2003, PROSECUTOR v. MILORAD KRNOJELAC, para. 218.

Prepared by:

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem