Introduction

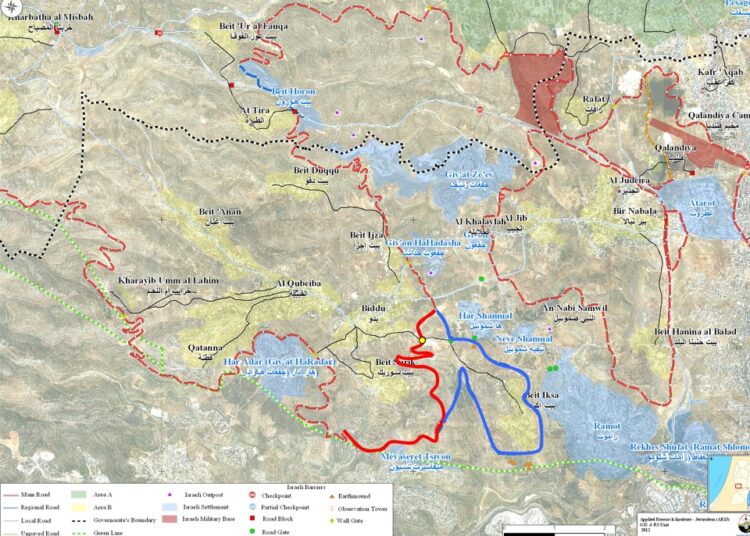

In a move that embodies Israel’s creeping annexation policy pursued for decades, three Palestinian villages located northwest of Jerusalem: Beit Iksa, Nabi Samuel, and Al-Khalaila, suddenly found themselves outside the Palestinian administrative registry and under direct Israeli control. This is no longer a matter of crossing permits or temporary security measures; it has turned into a redrawing of boundaries on the ground, reflecting the intersection of military orders with broader settlement policies aimed at reshaping the demographic and political landscape around Jerusalem. This measure is not an isolated step, but part of the “Greater Jerusalem” plan, which seeks to empty the city and its surroundings of their Palestinian population and consolidate a Jewish settler character.

Declaration of 20,000 Dunums as a “Seam Zone”

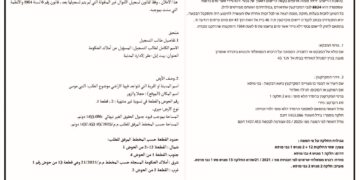

At the beginning of 2025, the Israeli military’s Central Command issued Military Closure Order No. (S/01/25), declaring approximately 20,000 Dunums (20 square kilometers) of Palestinian land north of Jerusalem, including the three villages, as a “Seam Zone.” The order enforces a strict military permit regime that severely restricts Palestinian entry and denies landowners the right to access or use their property.

This measure is part of a wider plan to link northwest Jerusalem with major settlements such as Giv’at Ze’ev, seen by Palestinians as a clear prelude to implementing the “Greater Jerusalem” project; amounting to “de facto annexation” of land and people.

The Concept of the “Seam Zone”: From Security to Control

The idea of the “Seam Zone” dates back to the early 2000s, when Israel began constructing the Segregation Wall inside West Bank territory. The wall, which cuts deep beyond the Green Line in most of its route, has trapped dozens of Palestinian villages and isolated vast areas of fertile agricultural land. While Israel claimed the move was for “security purposes,” the lands that ended up on the “Israeli” side of the wall were classified as Seam Zones, subjecting Palestinians to a complex permit system.

In practice, this regime did not “facilitate farmers’ access” as Israel claimed, but became an instrument to prevent them from reaching their land and gradually entrench its confiscation. Reports by human rights organizations such as B’Tselem and Human Rights Watch confirmed that Israel used this system to deepen control and dispossession, stripping farmers of their land and livelihoods.

Change from the Status Quo

In the Giv’at Ze’ev area, the wall was completed in 2010, enclosing some 20 square kilometers between the wall, Highway 443, and the Green Line. This left the villages of Beit Iksa, Nabi Samuel, and Al-Khalaila trapped on the “Israeli” side of the barrier, their residents subjected to strict checkpoint procedures at Al-Jib and Biddu checkpoints.

While residents were allowed to enter based on official lists, relatives, teachers, doctors, and service providers had to obtain special permits requiring complex security coordination. Farmers were forced to submit seasonal “individual” applications for permits to reach their land, an almost impossible process that crippled the villages’ economic and social life.

De Facto Annexation – Between Reality and International Law

The isolation of Beit Iksa, Nabi Samuel, and Al-Khalaila cannot be regarded as a mere administrative or security step; it represents a further stage of undeclared annexation. Subjecting these villages to Israeli civil administration instead of Palestinian records constitutes a grave violation of international humanitarian law, especially the Fourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits forced population transfers and demographic manipulation in occupied territories.

Israel treats these villages as if they fall under its sovereignty, despite being classified under the Oslo Accords as Areas “B” and “C,” and administratively managed by the Palestinian Authority. This contradiction reveals the silent annexation strategy; advancing gradually but steadily.

The Strategic Dimension: Greater Jerusalem and the Encirclement Belt

Turning 20,000 Dunums north of Jerusalem into a Seam Zone is not an isolated action, but part of a broader plan to establish a settlement belt encircling East Jerusalem from all sides. This belt stretches from Ma’ale Adumim in the east, through Giv’at Ze’ev in the north, to the settlement blocs in the south and west. The objective is clear: to completely sever East Jerusalem from the West Bank and consolidate it as Israel’s unified capital.

Humanitarian and Political Implications

- Deepening geographic and social isolation: The three villages have become isolated enclaves, cut off from their Palestinian surroundings.

- Restriction of daily rights: The permit regime has turned daily life into a maze of bureaucratic obstacles, pushing residents, especially younger generations towards displacement.

- Reshaping demographics: While Palestinians are suffocated by restrictions, surrounding settlements expand rapidly to reinforce Israeli dominance over Jerusalem’s perimeter.

- Closing the horizon for peace: Converting land into Seam Zones and annexing it de facto undermines the viability of a geographically contiguous Palestinian state.

Background on the Three Villages

- Beit Iksa: Located northwest of Jerusalem, covering 9000 Dunums with around 1400 residents. Since the wall’s construction in 2004, it has been isolated, accessible only through a military checkpoint. The village suffers from a ban on urban expansion and declining population growth.

- Nabi Samuel: A small village of 3500 Dunums, with only 1050 Dunums left after most of its land was confiscated and designated as an “Israeli national park.” It is home to about 400 Palestinians, living under harsh restrictions and frequent home demolitions.

- Al-Khalaila neighborhood: West of Jerusalem, covering 4000 Dunums, surrounded by four Israeli settlements threatening its existence. It has around 400 residents who face severe shortages in services and infrastructure.

Conclusion

The declaration of a Seam Zone north of Jerusalem reflects a broader battle over space, memory, and sovereignty. It is not a mere security measure but part of a long-term settlement project designed to empty the land of Palestinians through restrictions, confiscations, and pressures. This policy constitutes a form of slow, coercive displacement that redraws the demographic landscape around Jerusalem in Israel’s favor.

At a time when the international community continues to speak of a two-state solution, Israel is entrenching settlement facts on the ground that render such a solution unattainable, pushing instead toward an apartheid reality built on full Israeli control. In doing so, it buries any prospects for a just and lasting peace based on justice and the rights of peoples.

Prepared by:

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem