Introduction

The policy of changing place names represents one of the most profound and dangerous tools in the Israeli colonial project. It extends beyond administrative or technical concerns to the very core of Palestinian identity, memory, and collective consciousness. Renaming streets, cities, and historic landmarks, especially in Jerusalem, is part of a long-term strategy aimed at erasing Arab, Islamic, and Christian symbolism, and replacing it with a Torah-based colonial narrative that reshapes space in line with the Zionist project.

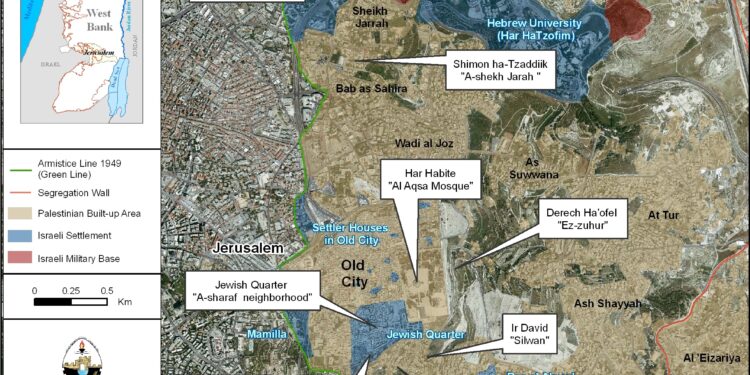

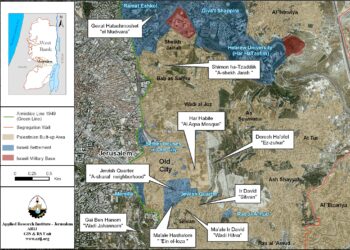

Jerusalem, with its profound religious and civilizational symbolism, lies at the heart of this conflict. It is not only a site for military and settlement practices but also a battleground for symbolic warfare targeting its demographic structure, public space, language, and names. Thus, the “colonial map of Jerusalem” emerges as the result of systematic policies that go beyond spatial control to attempt to redefine the city’s identity and erase its authentic Arab character.

Within this framework, the plan to replace Arabic names with Hebrew ones, stands as a central tool for reproducing the colonial narrative. This process is not limited to changing street signs or modifying maps; it constitutes a deliberate effort to erase collective memory, marginalize the presence of the indigenous population in public consciousness, and present Jerusalem to the world as an exclusively “Hebrew city.” Language becomes a weapon, and naming becomes a colonial tool to exclude Palestinians and strip the city of its history and culture in favor of an alternative colonial narrative.

Historical Roots of the Renaming Policy

Since the Nakba of 1948, Israel has pursued a systematic plan to reshape Palestinian geography through renaming policies. The “Government Names Committee” was established to such end and has renamed over 9000 sites; including villages, towns, valleys, and mountains, drawing on Torah texts and mythical narratives to justify these new names. The goal has been to replace original Arabic names with Hebrew ones and construct a colonial narrative based on the forged claim of a “land without people for a people without a land.”

These policies intensified in Jerusalem, especially after the occupation of East Jerusalem in 1967, when historic streets and neighborhoods were renamed, replacing Palestinian memory with new meanings. For example, the historic “Al-Sharaf neighborhood” was completely demolished and reconstituted as the “Jewish Quarter,” as part of a broader project to redraw the city’s spatial memory and impose a colonial narrative.

Symbolic and Political Dimensions of Renaming

In September 2025, Jerusalem witnessed a new and dangerous development: the occupation authorities decided to officially rename the route on public buses circulating throughout the city from Al- Buraq Wall to the Western Wall (AKA the “Wailing Wall”).

While this may initially appear as a minor administrative adjustment by the Israeli municipal authorities, its political and cultural implications are far deeper. It is not an isolated event but part of a comprehensive Judaization strategy targeting Al-Aqsa Mosque, its surroundings, and the holy city as a whole.

This policy accompanies several practices that collectively define an integrated approach, including:

- Daily intensified incursions into Al-Aqsa Mosque by Jewish settlers and Temple groups to establish a permanent presence.

- Renaming religious and historic landmarks in and around Jerusalem, extending beyond mere labeling to reshaping status and environment identity.

- Embedding a Torah-based narrative in public consciousness through media, education curricula, and public spaces.

The danger goes beyond symbolism: it institutionalizes a policy of “Judaizing public space.” Torah-related terms are no longer confined to books or political and media discourse; they have become part of the everyday landscape, visible on streets and public transport, shaping the consciousness of new generations of Israelis, and presented to international visitors-tourists as the “natural-native and historical name” of the whereabouts.

In this sense, renaming transforms from a municipal decision into a political strategic tool to reshape spatial and historical consciousness, reducing Palestinian visibility in the city and replacing it with a Torah narrative presented as the sole “historical truth.”

Naming as a Colonial Tool

Historically, renaming policies have not been mere administrative measures or cosmetic details; they have always served as essential tools in colonial projects to reshape space and memory according to the colonizer’s vision. Names carry symbolic meaning, embody collective memory, and consolidate identity.

Globally, similar practices have occurred. In Algeria, French colonizers replaced local town and mountain names with French ones, attempting to uproot local memory and impose a colonial identity. After independence, the original Arab names were restored, and renaming became a symbol of liberation and regained national sovereignty. In North America and Australia, European colonial powers rewrote maps with European names, erasing indigenous names to marginalize or obliterate the presence of native populations, both physically and symbolically.

The Israeli case, however, presents a more complex situation as it intertwine colonial and religious dimensions. Hebrew renaming policies do not merely attempt to erase Palestinian presence; they also attempt to confer a contrived Torah-based legitimacy to settlement. Assigning biblical names to Palestinian towns, villages, and mountains seeks to create an alternative narrative that justifies colonial existence as a supposed “historical and religious” prolongation. Renaming thus becomes an ideological discourse that legitimizes occupation while erasing the Palestinian narrative from geography and history alike.

Jerusalem in Focus

Arabic names in Jerusalem hold profound civilizational and spiritual memory, such as Bab al-Amud, Silwan, Jabal al-Mukabbir, and Al- Buraq Wall. Replacing them with Hebrew names; e.g., “Sha’ar HaHadashot” (Bab al-Amud), “Shiloh” (Silwan), “Har Hatzofim” (Jabal al-Mukabbir), and “Kotel/ Western/ Wailing Wall (Al- Buraq Wall); is not merely a linguistic change. It attempts to write a new history, erase Palestinian memory, and reshape the consciousness of future generations.

This trajectory reveals three interlinked dimensions:

- Symbolic and memorial dimension: Targeting names strikes at centuries of cultural memory, transforming Palestinian landmarks into colonial symbols.

- Political dimension: Judaization aligns with Israeli legislation, such as the 2018 Nation-State Law, which declared Hebrew the sole official language, marginalizing Arabic’s historical status.

- Colonial dimension: Names serve to consolidate control over both physical and symbolic space, reshaping collective imagination for locals and international visitors to align with the Zionist narrative.

The uniqueness of the Israeli case lies in this overlap of the sacred and political, religion and colonialism. Renaming becomes a tool for reshaping spatial and historical consciousness, representing one of the most dangerous aspects of the colonial project in Palestine, particularly in Jerusalem.

Options for Resistance: Where Symbolism meets Practice

Judaization and renaming policies go beyond spatial control, aiming to reshape Palestinian collective memory. Resistance strategies therefore extend from theory to practical tools in the battle over identity, including cultural, legal, and grassroots measures.

- Cultural and linguistic preservation: Using Palestinian names in daily discourse, media, and research/ academic works is a symbolic act of resistance, reaffirming Palestinian narratives in public space.

- Documentation and archiving: Digital initiatives like “Palestine in Memory” preserve original names and document renaming policies, creating historical databases to safeguard Palestinian memory.

- Legal and political avenues: Litigation, heritage protection, and UNESCO decisions reinforce cultural and historical rights.

- Popular and grassroots action: Community initiatives to post alternative street signs, teach Palestinian names to younger generations, and maintain awareness of historical heritage constitute active cultural resistance.

Resistance to Judaization is thus not merely a cultural choice but a comprehensive national project grounded in culture, language, law, and daily practice, affirming that names are living witnesses to Palestinian presence and historical rights.

Implications for Future Settlements and Conclusion

Israel’s systematic replacement of Arabic names with Hebrew ones across Jerusalem, stretching from Silwan to Bab al-Amud, Jabal al-Mukabbir, and Al-Buraq Wall and across Palestine, from Umm al-Rashrash to Tel al-Rabi’a, constitutes far more than a symbolic gesture: it is a cornerstone of the broader settler-colonial project. This policy of linguistic and cultural erasure not only seeks to normalize Judaization but also to render the restoration of Jerusalem as a Palestinian capital politically and symbolically “impossible.”

By eliminating indigenous place names, Israel undermines the memory of place and detaches Palestinians from their historical and cultural rights, thereby foreclosing the possibility of any equitable settlement that acknowledges Palestinian identity in Jerusalem. What appears, as a marginal battle over language is, in reality, a struggle over memory, belonging, and sovereignty; dimensions as decisive as land and borders.

In this context, resisting the renaming of places is not merely a cultural act but a national and political obligation, essential to safeguarding Palestinian historical continuity and ensuring that future settlements remain tied to the authentic symbols and narratives of the land.

Prepared by:

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem