1- ABSTRACT

The paper at hand briefly touches on the present-day and future influences and impacts of building the Separation Wall (hereinafter “Wall”) and its associated infrastructure (i.e. by-pass roads, physical obstructions, among others) on the social development of the Palestinian community in the West Bank territory.

The Paper will discuss notions of prosperity, sustainability, and viability of the Palestinian communities in the West Bank in light of the de-facto reality of the Wall. In addition, the paper will discuss the impacts on built environment, nature, and figure out its nexus with crucially needed social development of the Palestinian communities in the West Bank.

The adopted research methodology in this paper is built through deliberations on the available data sources in the forms of literature reviews, published reports, mapping interpretations and fieldwork investigations.

2- INTRODUCTION

In-depth research is hardly needed to prove the adverse influences and impacts meted out to the trapped Palestinian communities, between the Wall and the Green Line(AKA: Armistice Line) and to the whole Palestinian community in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, due to what became known later as the unilateral Israeli demarcation of borders with Palestinian communities, through the building of the Separation Wall (AKA: Segregation Wall and Apartheid Wall).

A walk on foot through the underdeveloped Palestinian streets besides the built parts of the Wall suffice to demonstrate the adverse implications of the Wall on Palestinians, who became abruptly detached from their farmlands, families and livelihoods on the other side of the Wall. Yet, while every facet of life in these Palestinian communities cries deliberate underdevelopment, things should be characterized in empirical proportion so as to arrive at a reasonable understanding of the dimensions of the Wall’s phenomenon.

On the Israeli side, the spoken reason for building the Wall is to secure the Israeli civilians from Palestinian’s attacks. However, on the Palestinian side, the adverse social underdevelopment of Palestinian communities in the West Bank finds expressions by the control mechanism of building the Wall on stolen Palestinian lands, aiming at demarcates “cantonize” the Palestinian’s living space by physical obstructions, as a mean of spatial re-distribution of demography and land and consequently delineating the political borders for the State of Israel. As the Israeli Justice Minister Tzipi Livni (Vice Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs now) declared in a conference in Caesarea: 'One does not have to be a genius to see that the fence (i.e. Wall) will have implications for the future border. This is not the reason it was built, but it could have political implications.' (Aljazeera Net, December 2005).

3- Statement of Arguments

The paper would argue that the spoken motive for building the Wall on behalf of the Israelis (i.e. purported for security reasons) is fallacious and entails other tacit dimensions of Jewish geo-demography dominance, which is considerably, affects the rightful social development of the Palestinian communities. However, first one has to thoroughly conceptualize the Israeli Separation Plan and its implications on the Palestinian built-environment.

4- THE ISRAELI SEPARATION PLAN

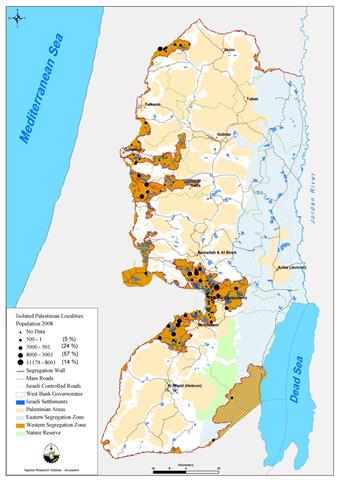

In June 2002, the Israeli Government embarked on its Separation Plan that expropriates about 40% of the total West Bank area (i.e. 5,661 km2). Almost one-third of expropriated area is located between the Wall and Green Line “Western Segregation Zone.” The other two-thirds of the confiscated area are the de-facto created “Eastern Segregation Zone” on the eastern side of the West Bank, which was created without walls or fences, but through its control of access points along the Jordan Valley and the shores of the Dead Sea (ARIJ GIS-Database, 2007), See map (1)

5- SPATIAL RE-DISTRIBUTION AND GEO-DEMOGRAPHY

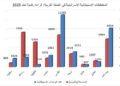

The mass area of the West Bank is 5,661 km2 and 2,517,047 Palestinians (PCBS, 2007) and around 500,000 Israeli settlers (ARIJ, 2007) inhabit it. However, since the Israeli Occupation of the West Bank territory back in 1967, about 8.5% (ARIJ GIS-Database, 2008) of the West Bank area was zoned as designated Israeli settlements and military bases and became off limits for the Palestinians, who were virtually capable of utilizing the remaining 5,179.8 km2, as the signed Oslo Agreement excluded more than 60% of the West Bank area and zoned it as area (C) that falls under full Israeli control. Relying on these numbers, the Palestinian gross population density calculated 486 capita/ km2 (i.e. 2,517,047/5,179.8). Now, after the Separation Plan has been introduced, the Palestinian gross population density tipped to 741 capita/ km2 (i.e. 2,517,047/3,396.6) (See figure (1)).

Figure (1): Palestinian Population Gross Density before & after the Wall

Thus, the gross population density has increased by approximately 50% during 5 years and this is interpreted due to the high rate of population growth and the limited access to open lands for future development. This is due to the land confiscation policies the Israeli government has implemented in the West Bank territory, epitomized by the Wall. This very high gross population densitywill probably results in urban sprawl and the misuse of valuable agricultural land. Other anticipated environmental problems such as congestion, pollution, the spread of slums and the rising numbers of urban poor will feature prominently as formidable challenges to the emerging Palestinian state in the coming years, unless dealt with them now.

6- MOBILITY OF PEOPLE AND GOOD

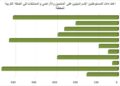

The Israeli adopted policy of physical domination through building the Wall on the Palestinian-Israeli borders, is manifested through a series of military terminals with the purpose of controlling the commercial flow of the Palestinian goods, merchants and workers from the OPT to Israel and, also, between the OPT area (See map (2)

This Israeli terminals' policy has served, according to human rights organizations, as a collective punishment strategy and as a source of impediments to Palestinians' movement along the snaky path of the Separation Wall. According to the World Bank's estimates, some 2–3 percentage points of the Palestinian Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per annum are lost due to the Wall (World Bank, 2006). This made the Quartet (during its Committee Meeting in December 2004) to advocate the dismantling of the Israeli closures' regime imposed on the OPT, including the Wall.

A thorough understanding of the locations of these military terminals reveals that these terminals are located in sensitive areas to block the usual routes that were used by the Palestinians until recently, creating a group of besieged Palestinian communities. These terminals are opened for Palestinians to access other adjacent Palestinian communities only at specific times and under ambiguous, harsh and inhuman Israeli procedures. Movement of people and flow of goods between towns and cities, farmlands and towns, and between the OPT and the world outside have been reduced to a trickle.

This politics of separation (Weizman, 2007, p.182) is similar to the Wall of the Panopticon (Myhawi, 2007, p.5) that separate the prisoners from the outside world; the Palestinians are enclosed in controlled areas, away from their livelihoods and families. Evidently, it became increasingly difficult for Palestinian public to commute easily across the Wall to access places of worship, families, education, institutions, and employment, thus, jeopardizing the social fabric “lifescape” of Palestinian communities. This could be flagrantly seen, as the majority of the expropriated lands due to the construction of the Wall are of a rural nature, where its residents depends extensively on the public services provided by the nearby urban centers, which were detached from the realm of its territorial contiguity.

7- Legitimacy of the Right for Social Development

The Palestinians argue the legitimacy of the Israeli military terminal policy by the virtue of international law, including the 'International Humanitarian Law (IHL)' that obligates Occupying Powers (i.e. Israel) to protect freedom of movement for the population of any Occupied Territory (i.e. Palestine), as well as their (Population under Occupation) political, economic, cultural and social rights. 'Everyone lawfully within the Territory of a State shall, within that Territory, have the right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose his residence.' (Article 12.1, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (OHCHR, 1966).

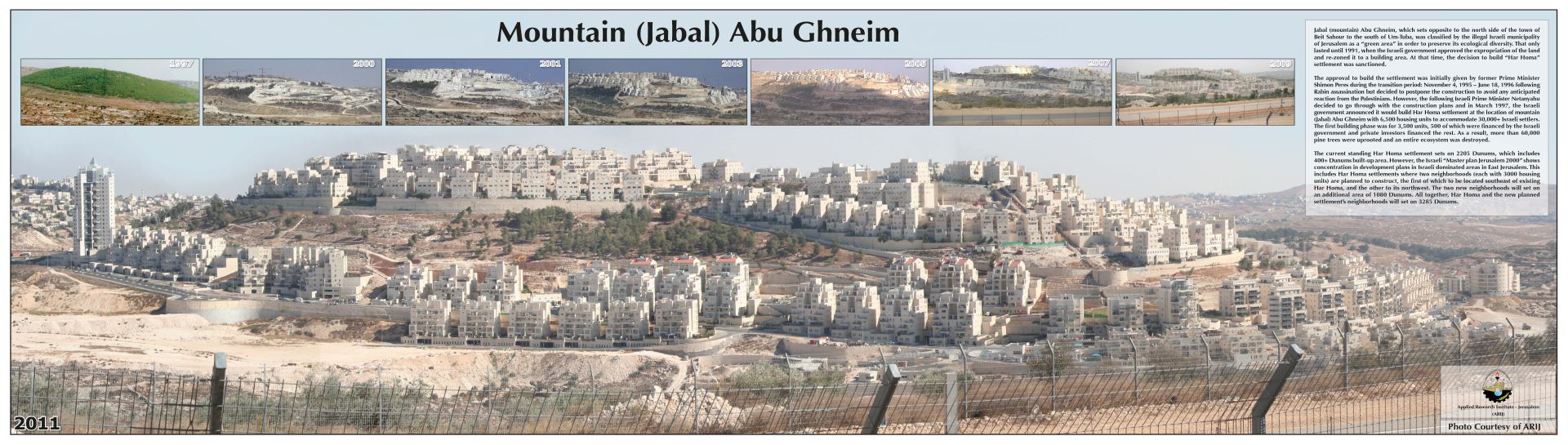

8- AGRICULTURAL BASE AT RISK

Land Use/Land Cover interpretation of the isolated Palestinian lands due to the building of the Wall shows that almost half of the area is of agricultural nature, plus other 11% of forests scenery (ARIJ GIS-Database, 2008). Anani (2007) called the former as “Agrarian Landscape,” which is characterized by a vivid change in its physique, due mainly to what he called rurbanization; the mix in the property (e.g. social and physical) of urban and rural areas to a degree that is regarded as interacting and inseparable.

To elaborate more, the perpetual and increasing migration from Palestinian rural areas to the urban ones, due to the Israeli oppressive practices, including the Wall, has its adverse effects on both sides. However, the borders between these urban areas and its rural hinterlands can be best described by the term used by Raja Shehadah (2006), “Vanished Landscape” due to the growth rates of urban sprawled areas and the uncontrolled expansion of villages in the direction of urban centers. Consequently, the organic relationship between Palestinian work force and agrarian landscape became more fragile, jeopardizing the agricultural production-consumption cycle of agri-economics.

Weber (1991) argues that those who are disconnected from their production-consumption relationship with the landscape tend to protest and resist. On the Palestinian arena, nucleus of civil protest and resistance, as in Ba’lian and Na’lin in the northern separated parts of the Wall, provide an aspiration and motivation for other Palestinians that something could be done to stop the crime of the Wall against Palestinian lands and people.

9- THE CASE OF BEIT HANINA – EAST JERUSALEM

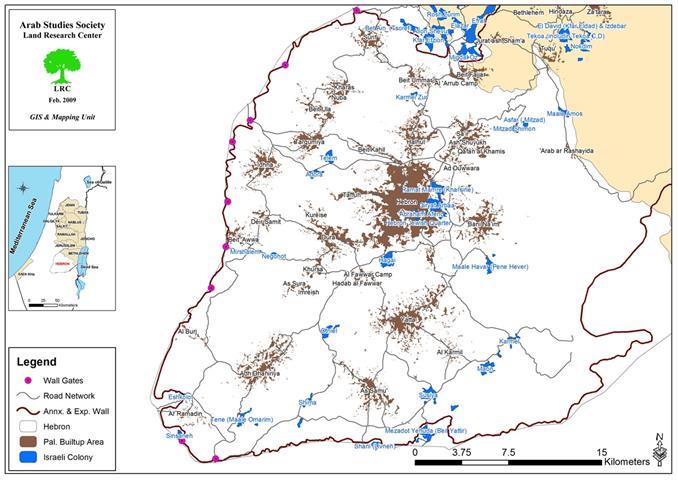

Beit Hanina; a Palestinian town located 5.5 km north of Jerusalem City. It is surrounded by Al-Ram & Dahiyat Al-Bareed from the north, Bir Nabala, Al Judera and An Nabi Samuel villages from the west, shu'fat town and a series of Israeli settlements from the south, and the settlements of Pisgat Ze'ev, Pisgat Amir and Neve Yacoov from the east (See map (3)

Beit Hanina's total land area is 16,284 dunums, out of which 588 dunums constitutes the built-up area, which is divided into two, Beit Hanina and Beit Hanina Al Balad. The population of Beit Hanina town totals about 3,000 inhabitants (PCBS 2006), other than that cultivation makes up a fair share of Beit Hanina's residents livelihood, in addition to being an olive trees basin.

According to the Oslo Agreement, the lands of Beit Hanina town were classified to areas, B and C that falls under Israeli control; but none of the town's area was classified as Area 'A'. A total of 588 dunums were classified as Area B (3.6 % of the total town area) where most of the built up area is concentrated; while the remaining area, a total of 15,696 dunums (96.4% of the total town's area) of Beit Hanina town lands were classified as Area C that contains all the agricultural lands, forests and open spaces.

The Wall runs at 8.2 Km on Beit Hanina lands, starting near Atarot Industrial zone in the north (See map (3) in annex). Upon Completion, the Wall will isolate 3,102 dunums of Beit Hanina's town total land area, which include the designated open spaces for future expansion and some agricultural lands that residents of Beit Hanina may tend to utilize after expectedly losing their jobs as workers in the construction sector inside Israel.

Upon completion also, the Wall will cause the indirect isolation of an additional portion of Beit Hanina's town lands, a total of 1738 dunums, at its western edge (See map 3 in annex), as land owners will not be able to access it, due to its location between the route of the Wall and the Israeli settlements of Ramot and Rekhes Shu'fat. This in turn may push people to sacrifice the remaining agricultural lands to accommodate population growth in the coming years, bearing in minds the high gross population density of Beit Hanina town that stands at 520 Capita/km2 (PCBS 2006) (See footnote no. 4).

The Separation Wall effectively cuts-off Beit Hanina Al Balad from the town’s main urban center. Palestinian residents living in Beit Hanina Al Balad are no longer able to access the town's urban center because the Wall entraps them along with Beir Nabala, Al Jib and Al Judera villages in one isolated enclave, where the only exit for them is through an alternative detour road to Ramallah City, which is 6.5 km away and consumes one and a half hour of time.

10- CONCLUDING NOTES

Changing the borders from green to gray-concreter, as expected didn’t and wouldn’t end the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians that was characterized by Edward Said (1998) as “two separate narratives converging on the same landscape.” On the contrary, the Israeli Occupation practices, epitomized by building the Wall have resulted in resource depletion, shortage in fresh-water supplies, degradation of the environment, increases in unemployment, increases in poverty rates, decreases in agricultural production, and in incapacitating the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) to adequately fund and develop social infrastructures for the Palestinian communities, as it (i.e. PNA) has lost control on land designated for present-day and future social development.

Coercing facts on the ground using the Wall as a tool was approached by employing the knowledge in architecture and planning. However, these disciplines could also be used, as a tool of resistance “Reality must be approved not accommodated to” (Said, 2000, p. 67). These ways of resistance need more concerted efforts from Palestinians to unfold its added value to their struggle against Israeli Occupation practices including, the Wall.

It is evident that all facets of Palestinian development including, the social facet was and is affected by the Wall, in a way that makes envisioning sustainability and viability of the Palestinian community a fairytale. However, these concluding notes are dictated by: “There is no sustainable social development for Palestinian communities, under Israeli Occupation practices, optimized by the Separation Wall.”

11- BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SOURCES

-

Aljazeera Net, December 2005. Israel May Turn Fence into Border. <http://english.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/E23DD66A-8797-4164-8711-45047ECF7128.htm>.

-

Anani, Yazid (2007), Palestinian Landscape Values in Turmoil.

-

Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem – ARIJ, GIS Database, 2007 & 2008

-

Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem – ARIJ, Status of Environment in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, 2007

-

Benvenisti, Meron (2000), Sacred Landscape: The Buried History of the Holy Land since 1948.

-

Foucault, M. (2000), Essential Works of Focault 1954-1984.

-

Muhawi, Farhat (2007), A Landscape of Surveillance and Control.

-

OHCHR – Office of the United Nations' High Commissioner for Human Rights. 1966. <http://www.ohchr.org/english/law/ccpr.htm>.

-

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics – PCBS, 2004 Seminar Day: population and Development – April, 2006 – In Arabic

-

Population Reference Bureau – PRB, 2005 World Population Data Sheet <http://www.prb.org/pdf06/06WorldDataSheet.pdf>

-

Said, Edward (1998), Palestine: memory, innovation and Space

-

Said, Edward (2000), The End of the Peace Process: Oslo and After.

-

Weber, Max (1991), MaxWebber: Essays in Sociology.

-

Weizman, Eyal (2007), Hollow Land – Israel’s Architecture of Occupation

-

World Bank: 'An Update on Palestinian Movement, Access, and Trade in the West Bank and Gaza' August 2006 <http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWESTBANKGAZA/Resources/M&ASummary+Main+MapAugust31.pdf>

:::::::::::::___

[1] The 'Green Line'—the internationally recognized boundary between Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT)—is the border Israel and neighboring Arab states agreed to in an armistice to end the War of 1948.

[2] Under international laws and United Nations Security Council resolutions, these settlements and military bases are deemed illegal.

[3] The figure 3,396.6 km2 stands for the remaining area of the West Bank after subtracting the Western and Eastern Segregation Zones that calculates 2,264.4 km2 (i.e. 40% of the West Bank area).

[4] This is considered very high when compared to the world average of 48.3 persons/km². In the less developed areas of the world the density is 63.7 persons/km² and the average in Asia which reached 45.2 persons/km² (PRB, 2005).

[5] Up to this moment, the Israeli governments, through a series of military orders, have declared the construction of 24 terminals, including 17 in the West Bank and 7 in the Gaza Strip (ARIJ GIS-Database, 2007).

[6] Even Danny Tirza the architect of the Wall characterized the continuously deflected and reoriented path of the Wall, during its construction, as “a political seismograph gone mad.” (Weizman, 2007, p.162).

[7] Panoptican is an architectural system presented by Jeremy Bentham’s. It consists of a ring shaped building that is divided into cells that face the interior, as well as, the exterior through big windows to “scan the greatest number of faces, bodies, attitudes, in the greatest possible number of cells” (Focault, 2000, p.72).

[8] The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), located in the OPT, estimated that 15-20% of Palestinians’ daily work time is lost on account of internal closures.

Prepared by:

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem