As the Israelis occupied the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), and the Gaza Strip (occupied Palestinian territory-oPt-) in June of 1967; the entire Mandate Palestine became one open space of movement. The Israelis aimed to display their absolute command of the territory but more so to charade geographical integration using economic tools to legitimize and fortify their presence in the face of the Palestinians aspirations for and independent state of their own.

Despite the fact that it was a military occupation, the oPt residents; the Palestinians enjoyed some sort of freedom when it came to movement; at least for the 20 years that followed the occupation. In 1987, the first Intifada broke out and it was not long when the occupation started to impose certain restrictions on movement, which started to shape with the magnetic card regime in 1989 for Gaza residents in particular and also to issue distinct identity cards for those who pose security threat to the occupation. During the 1991 Gulf war, Israel imposed full restriction on movement between the oPt and beyond the Green Line (Israel). In 1993, Israel initiated first restriction procedures on Palestinians’ travel to East Jerusalem.

For Israel, to implement the law was not a priority, however, the fact that restrictions on Palestinian movement was regulated that was the notch the Israelis used to initiate systematized restrictions on Palestinians’ movement, which also was paralleled by the Israeli instigation of the bypass road network (mainly for Israeli settlers) under the pretext of “response” to the first Intifada; with the purpose of bypassing Palestinian population centers. The bypass road system would be gradually be employed during the 1990s and fully comprehensive with the break of the Second Intifada in the fourth quarter of 2000.

The onset of the Israeli permit regime, the procedures were relatively accommodating; people received permits almost at well; even vehicles were provided with permits to travel on what started to identify as the Israeli road network. The permits were issued over various ranges of causes, of which: medical treatment, merchants, employment, and the VIPs (very important people). Unlike today, vehicles might be permitted, it was easier to acquire permits, and checkpoints could often be bypassed with relative ease.

Within the oPt, which was classified according to Oslo Accords to various levels of administrative control in order to facilitate transfer of areas from the Israeli Army control to the Palestinian Authority (PA) administration (Area A, representing 17.5% of the West Bank, where the PA exercises both civil and security control, Area B, representing 18.5% of the West Bank, where the PA exercises civil control and the Israeli Army exercises security control, Area C, representing 61% of the West Bank, where both civil and security control remain firmly under the control of Israel). Roughly 86% of the West Bank population resides in Areas “A” and “B”.

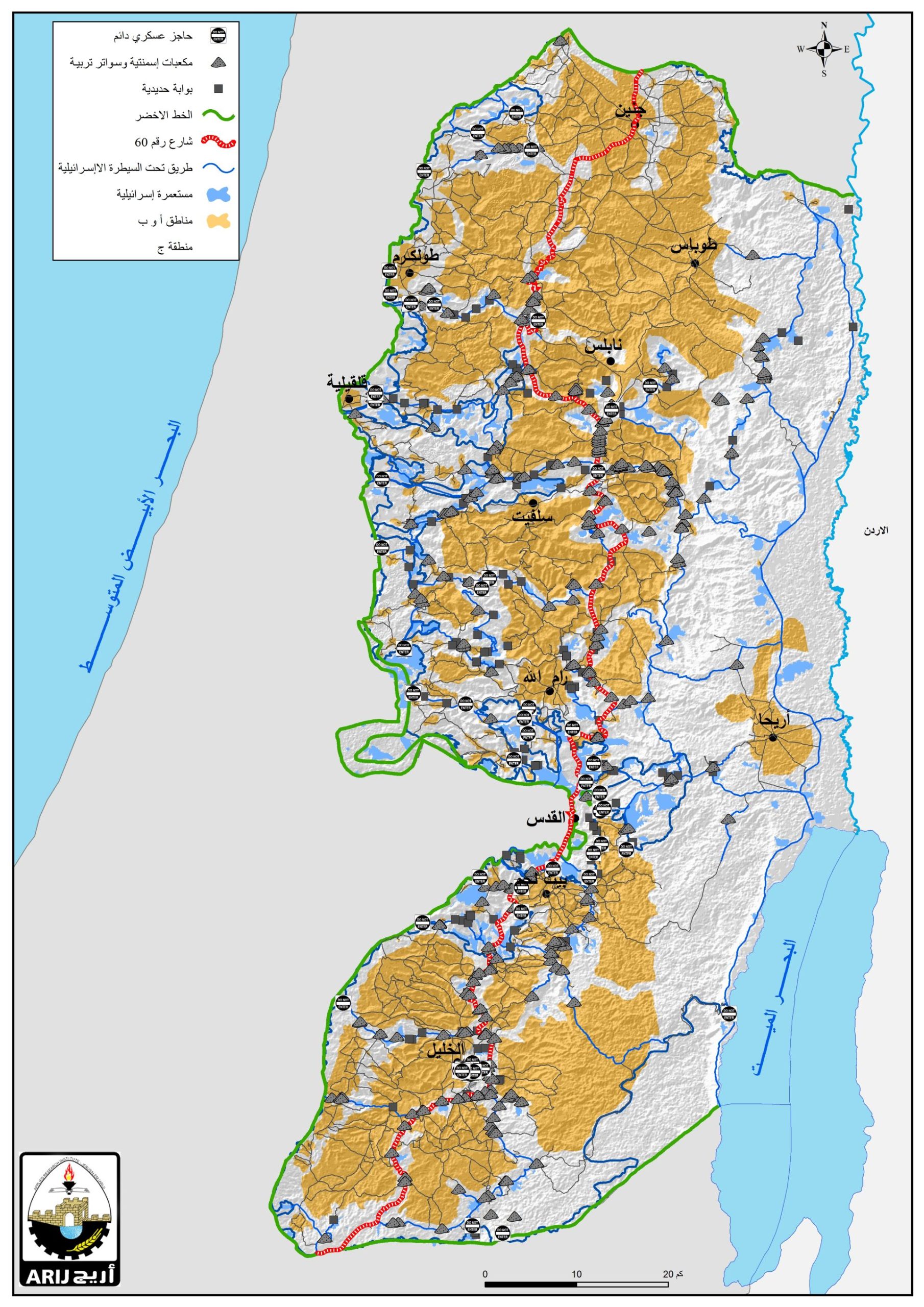

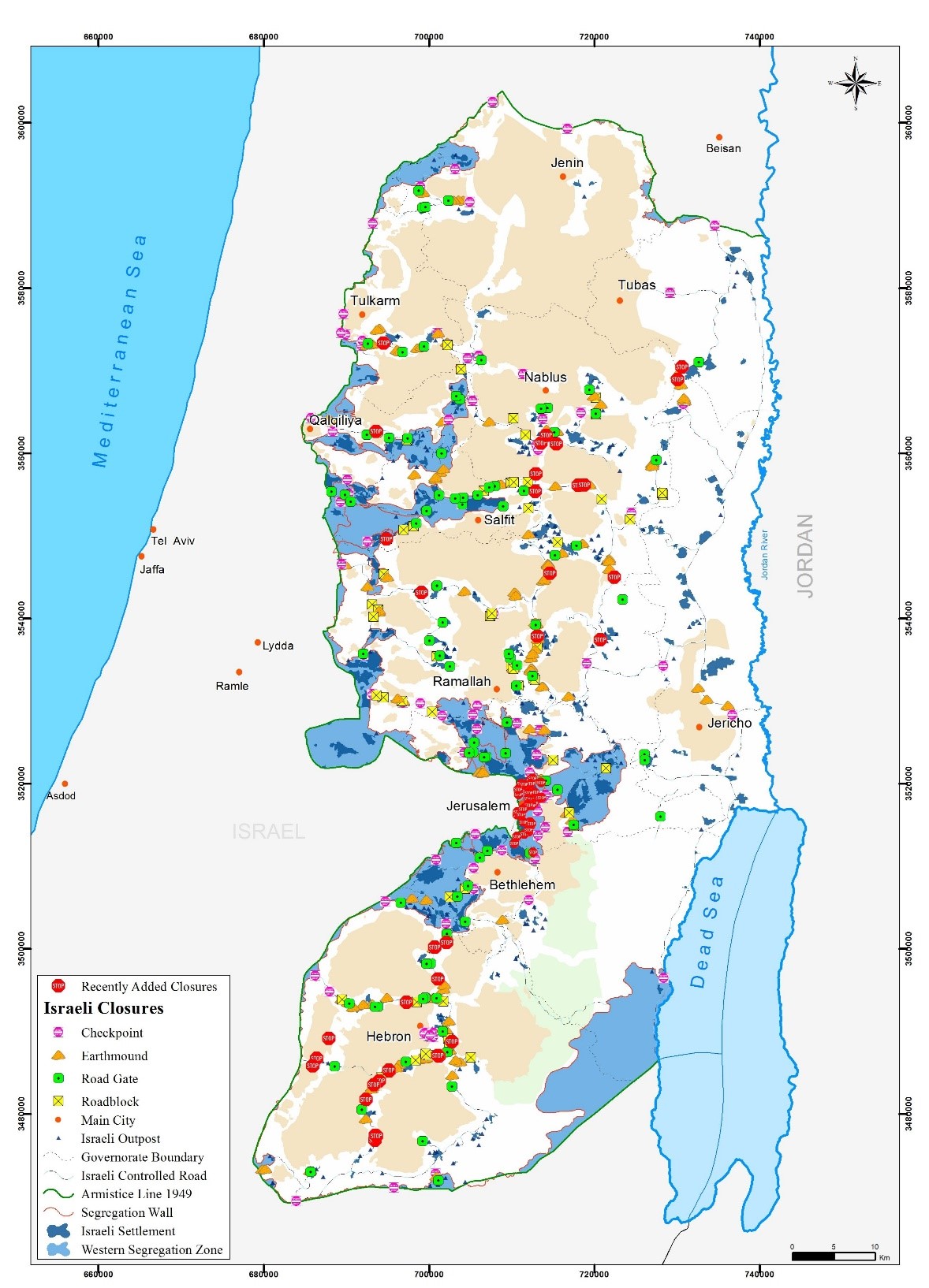

Even though Israel has control over area “C”; the permit system was not applied there; instead, Israel employed a matrix of control on the Palestinians’ movement within the West Bank that restricted Palestinians’ right to drive on certain roads or parts of it, while other roads were completely forbidden to use by Palestinians. Over all, Israel controlled the oPt through variety of obstacle; some 705 by the end of 2018, which included: permanent checkpoints, partial checkpoints, flying checkpoints, road barriers, roadblocks, road gates, wall gates, earth mounds, and trenches.

A permit regime to access certain areas; mainly the area beyond the segregation wall; known as western segregation zone (WSZ), which is the area isolated between the segregation wall and the 1949 Armistice line (the green line). The segregation wall that Israel started to construct back in 2002 under the pretext of security is set to stretch 771 km in length. As of June 2018, 63% of the barrier has been constructed, 3.5% is under construction, and 33.5% remains planned.

The total land area isolated in the WSZ is 705 km2, representing some 12.5% of the West Bank’s total land area of 5661 km2. Of the 705 km2 , 47% is agricultural land, 32% forests and open space, 4% Palestinian built-up areas, and 17% Israeli settlements and military bases.

Despite the security argument made by Israeli officials and militants on the purpose of the wall; testimony of relevant primary designer of the wall indicated otherwise, “the main thing the government told me in giving me the job was to include as many Israelis inside the fence and leave as many Palestinians outside,” adding that “the idea was to do it with balance.” Accordingly, the WSZ incorporates 107 Israeli settlements and some 664,000 settlers, representing over 85% of the West Bank settler population. As for Palestinians, the WSZ incorporates some 374,000 Palestinians and 90 localities. In total, 150 Palestinian communities have lands located in the WSZ.

The study highlights the Israeli matrix of control applied in the oPt and its economic and environmental impact. It also concluded that there were about 15 major Israeli checkpoints controlling the movement of Palestinian in the West Bank, and 11 major Israeli military checkpoints controlling Palestinian access to East Jerusalem and Israel.

Employing 70 vehicle with tracking devices for a period of 6 months (January – July 2018), more than 18 million records were registered and stored. The records showed total annual delays at checkpoints and ultimately Palestinian labor force time loss of almost 60 million hours, costing Palestinians approximately $410 million USD,

The environmental costs was no less horrifying when calculating along with the congestion and the average annual costs of delays to the Palestinian labor force, the annual emissions from additional fuel consumption were calculated at some 81 million liters of fuel, at a cost of nearly 135 million USD, producing additional 196,000 tons of CO2 emissions.

To read the Arabic abstract, click here

Prepared by:

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem