The construction of the Wall and its associated regime impede the exercise by the persons concerned of the right to work, to health, to education and to an adequate standard of living. This excerpt, from the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) concerning the legal consequences of the construction of a Wall in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt), shows the impact of the restriction on movement in the oPt on health. This paper aims at documenting the consequences of the restriction on movements in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip on the health of Palestinians and the development of the health sector in the Occupied Palestinian territories. Because of a greater availability of sources, this paper tends to concentrate more on the consequences on Health of the restrictions in the West Bank than in the Gaza Strip. I decided to focus on the consequences of the Wall on the health sector in the West Bank and in the Gaza Strip, and therefore not to examine the reasons and the background behind the construction of the Wall.

Health was defined, in the 1948 constitution of the World Health organization (WHO), as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. The restriction of movements in the oPt must also be defined, and distinguished: in the Gaza Strip, a severe blockade affects the flow of goods and people since June 2007. Unless they have a special permit, Gazans cannot get out of the Gaza Strip; conversely, West Bankers are not allowed to enter Gaza. In the West Bank, a Segregation Wall (also referred to as the Segregation Barrier) and an associated regime of checkpoints and closures prevents the free movement of people within the West Bank. The construction of the Segregation Wall was approved (and started) in 2002 by the Israeli government, following an outbreak of the second Palestinian Intifada in their struggle for freedom and liberation of the Israeli occupation and the settlements built illegally in the oPt following the 1967 war and Israeli occupation. It is still not completed, as the route for some sections of the Wall is highly contested.

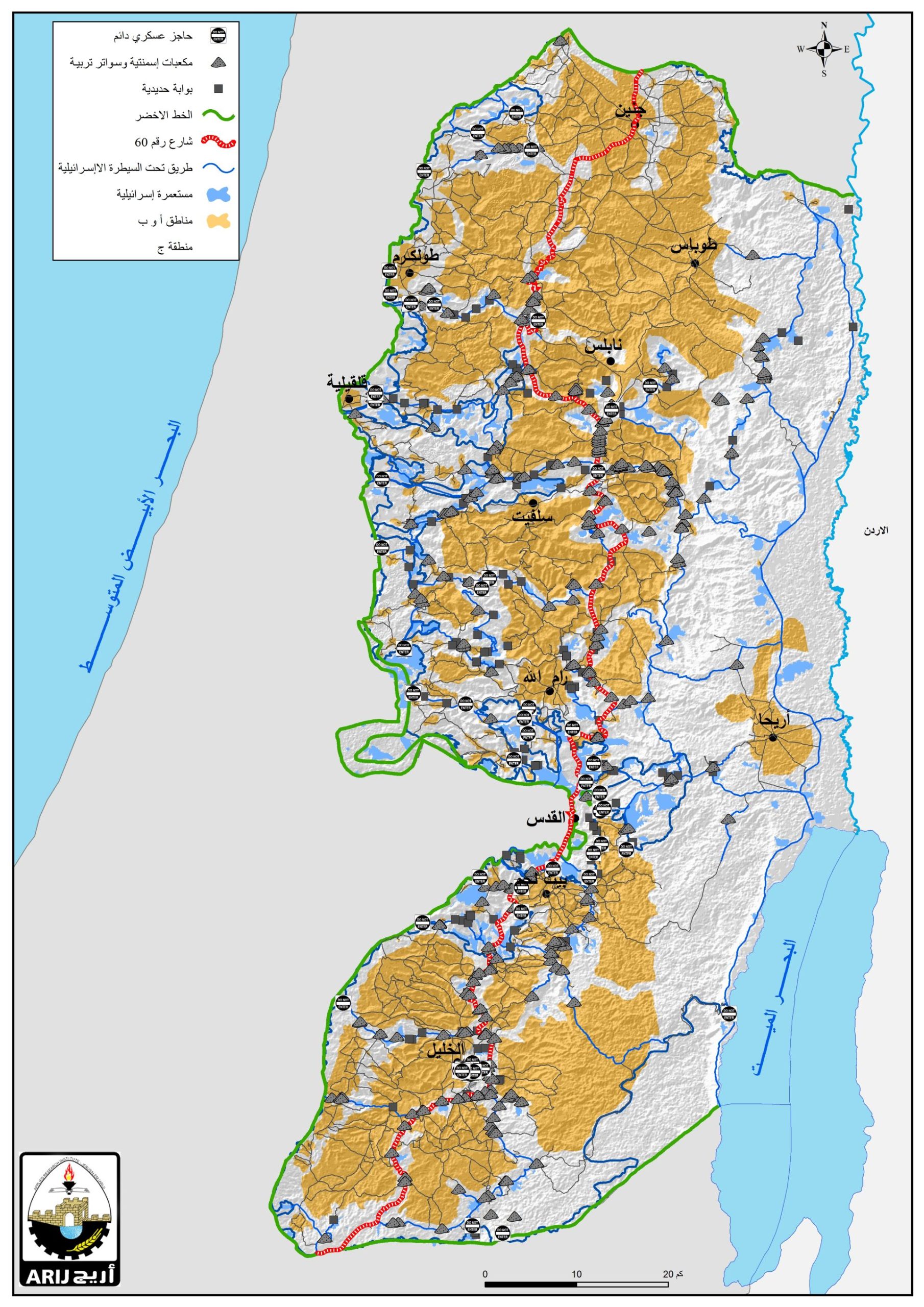

In the West Bank, in 2008, more than 630 blockades, checkpoints, road blocks, earth mounds and other various types of obstacles, affected the freedom of movement within the West Bank. These obstacles contribute to the large increase of travel time needed to reach the closest available hospital for Palestinians in the West Bank. Checkpoints can be permanent and partial, but also temporary (the flying checkpoints); this last type of checkpoint, because of their unpredictability, may be a bigger problem than the usual ones, as they can block a road anywhere, anytime. The other kinds of blockades (earth mounds, road blocks, etc) are fixed and intend to block a road, in order to oblige people to take a road controlled by a checkpoint. These various blockades severely hamper the freedom of movement of the Palestinian people. Map 1 shows the locations of the main blockades in the West Bank.

Map 1: The different Israeli physical obstructions in the West Bank (ARIJ database)

The restrictions on movement lead to the inaccessibility for the Palestinians of different places, including medical facilities. The inaccessibility is not measured in terms of distances, but in terms of time needed to travel from one place to another. Distance here is not a relevant factor, as restrictions on movements do not increase the distance between two locations, but significantly modify the travel time between them. We may therefore wonder how the restriction on movements in the oPt affect health conditions and undermine the Palestinian Health sector.

I) A long Journey to access Healthcare: the dramatic increase of travel times to healthcare facilities

The total length of the Israeli Segregation Wall currently under construction since 2002 will be 774 kilometers once its completed, according to the last version of the route, while the 1967 the 1949 armistice Line (also called the Green Line) is less than half this size (350 kilometers

). The Wall encircles the major Israeli settlements in the West Bank, including their potential future developments, their natural growth. In 2010, 85% of the settler population (of 600+ thousands) in the West Bank was located west of the Israeli Wall.

Almost 13% of the territory of the West Bank is located between the Green line and the Segregation Wall. 94% of the Segregation Wall, is inside the West Bank, while it should run along the 1949 Armistice Line.

There are currently more than 630 blockades in the West Bank, in a territory of around 5661 square kilometers, which implies that blockades of various types are extremely frequent in the West Bank. All these blockades do not present the same obstacles for West Bankers: earth mounds for example are physical obstacles, usually impossible to cross, which force people to take detours, but do not require, like the checkpoints, to wait in a line to be checked, in order to get through.

As for the Gaza Strip, a blockade is imposed by Israel since June 2007, which very severely restricts the freedom of movement and the trade of goods between the Gaza Strip and the rest of the world, especially the West Bank . Every day, Palestinians have to deal with these blockades, which increase significantly the travel times from one city to another and from the houses of the patients to the nearest medical facility.

The city of Qalqilyah, totally isolated from the rest of the West Bank, provides a very good example of the Segregation of some Palestinians cities and villages, from Israel, but also from the rest of the West Bank; the city is totally encircled by the Wall; the road which leads to Qalqilyah is controlled by an Israeli checkpoint. The only way out of the city (and the only way in, as well), the only connection of the town to the rest of the world is this checkpoint. To exit the city requires going through this checkpoint, which may take some time (the delay being extremely variable and could range anywhere from 5 minutes to 3 hours) and endanger the life of a patient who would need to access rapidly a medical facility out of the city. Indeed, Qalqilyah lacks specialized health care services; available only in neighboring cities, but the access to these medical facilities is made difficult and long by the Wall and diverse blockades. Qalqilyah also benefits from rather good primary healthcare services; but while patients from neighboring communities used to come to Qalqilyah, they have stopped because of the inability to enter the city. Qalqilyah is not the only enclave in the West Bank, and examples of cities surrounded by the Wall on three or the four sides include the Palestinian communitties in the Gush Etzion settlement block area (like Battir), the village, or the village of Azzun Atma for example.

15% only of households in the West Bank have access to a private car; the others have to use public transportation to move from one place to another. Generally, the fact not to be able to rely on a private car does increase the time needed to reach medical facilities. Indeed, the reliance on public transportation reduces the possibility of reaching a medical facility in a short period of time.

In 2010, it is estimated that around 25000 people in the West Bank (approximately 1% of the population) did not have any access to a medical facility whatsoever, and 285 000 people (11% of the population) had to go through one checkpoint or more to get to the closest hospital.

Knowing that delays at checkpoints may be extremely long in some cases (the delays are extremely variable, but can reach 3 hours), this shows the risks checkpoints involve for health.

Usually, ambulances benefit from a priority right to cross the checkpoint, but this right is not always respected, which lead to potentially life-threatening delays.

|

Table 4.1: Values for estimated delay at checkpoints

|

|

Average longest

|

194

|

|

Average Shortest

|

15

|

|

Mode Longest

|

120

|

|

Mode Shortest

|

5

|

Source: EKLUND L., Accessibility to Health Services in the West Bank, Occupied Palestinian Territory, 2010

Affected population by the estimated accessibility

Source: EKLUND L.,

Accessibility to Health Services in the West Bank, Occupied Palestinian Territory, 2010.

-

Good accessibility < 15 minutes

-

Intermediate accessibility: 15-30 minutes

-

Bad accessibility > 30 minutes

As an illustration, the table above shows the impact of delays at checkpoints on the accessibility to healthcare facilities. In the cases of a 15-minute delay at checkpoints, more than 200,000 Palestinians would be considered to have a bad accessibility to healthcare facilities, i.e. requiring more than 30 minutes to reach the closest hospital or clinic, potentially endangering the life of patients. If delays at checkpoints reach two hours, which remains quite rare, 321000 West Bankers would be considered to have a bad accessibility to a medical facility. These various figures eloquently show the extent of the restriction on movements, but also the potential risks for the health of Palestinians in the West Bank. In other words, since June 2002, the construction of the Wall has steadily added another layer of obstacles isolating, fragmenting and thus deteriorating the Palestinian healthcare system

], the NGO Médecins du monde notes.

In the village of Abu Dis, the journey to the nearest hospital skyrocketed, from 10 minutes before the construction of the Wall to almost 2 hours (1h50 minutes)

. In these conditions where the restriction on movements is particularly obvious, we can see that the Wall endangers the life of Palestinians in case of emergency. The impossibility to access a medical facility in less than 110 minutes, contributes to deteriorate health conditions in Palestine and sometimes to the death of Palestinians. The case of Abu Dis however is just an example of the consequences of the restriction of movements on the access to healthcare facilities.

The study led by the Health, development, Information and Policy institute in 2004 highlighted that the construction of the second phase of the Wall, would create 22 vulnerable pockets, isolated from the rest of the West Bank, accounting from nearly half a million people.

Medical cases such as heart attack, or asthma crisis, require medical care as early as possible, the first hour being of the utmost importance to save the patients life. Similarly, pregnant women, after the water broke and who have gone into labor, need to reach a medical facility as soon as possible; however, the Palestinian ministry of Health and several NGOs have reported cases where women about to deliver were stopped at checkpoints. The Palestinian Ministry of Health reported that since 2000, at least 68 Palestinian women gave birth at Israeli checkpoints, because of delays; the lack of medical help and the conditions of hygiene at checkpoints led to 35 miscarriages and the death of 5 mothers at these checkpoints. As we can see, the increase in travel times does severely jeopardize the patients life in cases of emergency.

The United Nations humanitarian report on the oPt in 2007 stated that a rising number of Palestinians died because of the delays, or the denial of access at Israeli checkpoints. The Monitor, a monthly report of data and field information gathered by United Nations agencies, highlights that between 2000 and 2007, 48 people died at checkpoints, because of the inaccessibility of medical attention.

.

All in all, the Segregation Wall severely infringes upon the right of Palestinians of the West Bank, Gaza, and to a smaller extent of East-Jerusalem to rapid medical treatment; the restrictions on movements, both of the medical staff and of the patients themselves, provoke the worsening of the situation of numerous sick people in need of treatment. This violates the right to health, written in the preamble of the World Health Organizations constitution, whose Israel is a member of.

II) The dramatic reduction of the availability of medical services

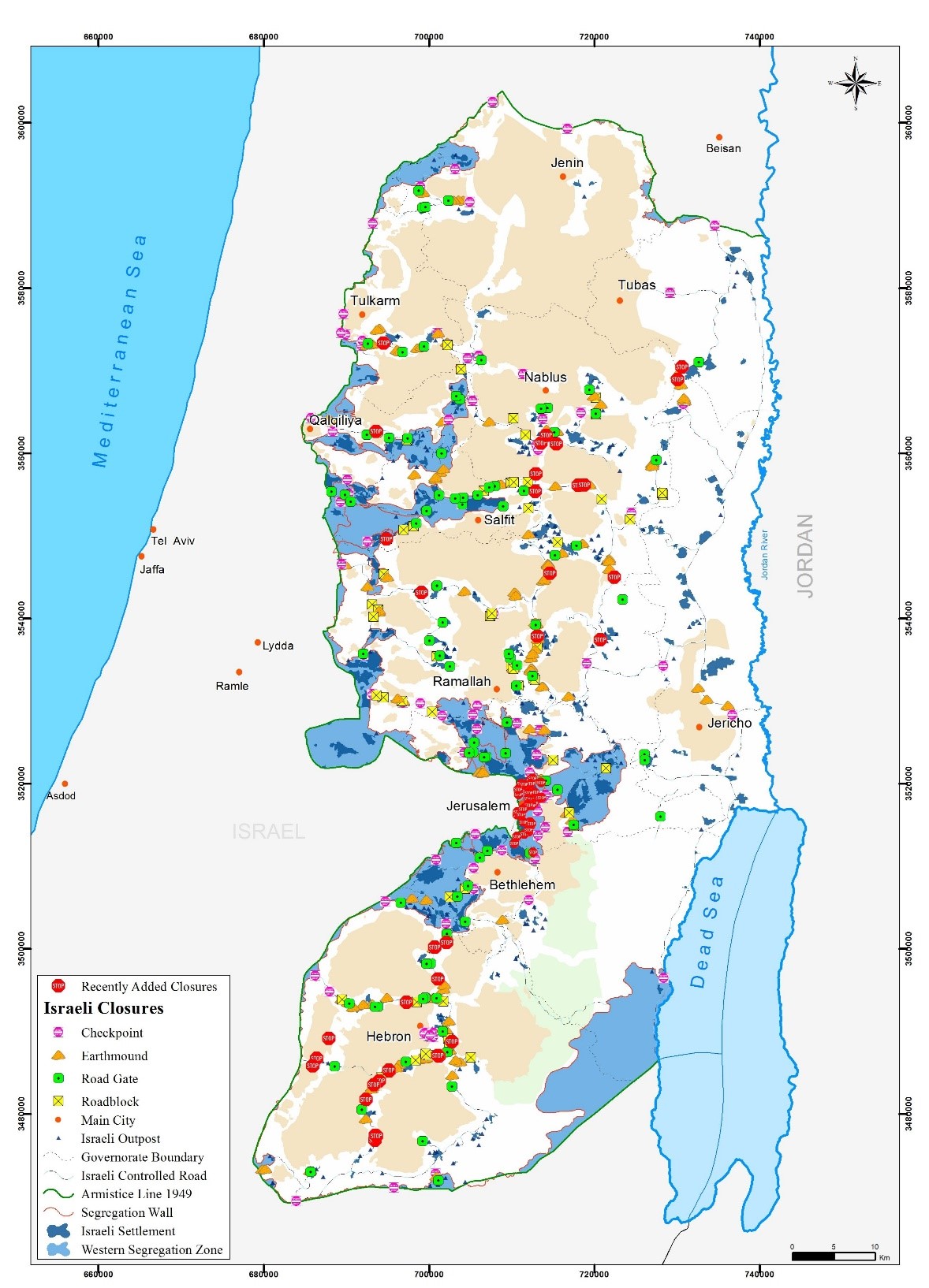

In the West Bank in 2006, there are 452 clinics running, according to the ARIJ GIS database, located as follows on map 2.

Map 2: Hospitals and clinics in the West Bank. Source: ARIJ, 2009

As a consequence of the construction of the Wall, inhabitants of the oPt will no longer have the same variety of choices (if they have any choice) for the medical facilities they want to go to, as many of these medical units, which used to be easily accessible, became remote because of the Wall and other blockades. Because of the Wall and the resulting restriction on movements, many people are able to access only a primary healthcare center (a basic level of health care that includes programs directed at the promotion of health, early diagnosis of disease or disability, and prevention of disease, according to Mosbys medical dictionary); to reach secondary healthcare (still according to Mosbys medical dictionary, an intermediate level of health care that includes diagnosis and treatment, performed in a hospital having specialized equipment and laboratory facilities) but the Wall makes it much longer to reach an adapted healthcare facility, which can provide more advanced, technical diagnosis and treatment than small clinics in rural areas. Therefore, when one inhabitant of a rural, remote area, needs specialized health care, he/ she has to move to a town where the service he/she needs is available. This need, however essential, is subject to the restriction on movements; cities where these services are available can be reached only after going through one or several Israeli checkpoints. For villagers encircled by the Wall, the availability of choices for a rapid treatment will often be reduced to primary healthcare centers, without the advanced means of bigger facilities.

The isolation created by the Segregation Wall implies other challenges, notably the dispersion of the medical care supply; the lack of skilled staff poses a great problem to medical units in the West Bank, notably because of the dispersion of such units.Particularly vulnerable are the inhabitants of the Seam Zone, for who health services are generally poor; in this sense, the Wall will contribute to the worsening of the health of the inhabitants of the oPt and the problems that its health system has to cope with. The distribution of health care facilities is affected by the Wall, since it tends to isolate some areas and some facilities from the rest of the West Bank (particularly in the seam Zone). But on a broader scale, the restriction on movements makes the clinics harder to reach.

In this sense that it reduces the possibility of choice of service and the general availability of some essential services (such as lab tests or medicine availability, see infra), the Wall as well as the blockade in the Gaza Strip do severely undermine the development and the quality of the Palestinian health services.

Furthermore, the Wall also severely restricts access to East-Jerusalem, where 12% of available hospitals beds are located; some specialized medical services are not available anywhere in the West Bank except East-Jerusalem. Every Palestinian who does not have Israeli citizenship or a residency permit in East-Jerusalem has to apply for a permit to enter Jerusalem

]; to enter for medical reasons, a patient has to undertake a long process; the permits are not automatically granted, far from it; in cases of general closures, for Jewish holydays or security alerts, the Wall may be closed and prevent the patients from having access to the specialized medical treatment they need.

For specialized health care in some fields, such as dialysis or cancer radiations, access to East Jerusalem is necessary, as this kind of medical procedure is available only in the East Jerusalem hospitals; yet, the Wall makes it hard to reach, with the necessity to obtain a permit from the Israeli authorities. Patients requiring dialysis need extremely frequent visit to the hospital, to proceed to the dialysis (everyday for severe cases). Pediatric dialysis or radiations against cancer are performed at only one hospital for the oPt, in the Augusta Victoria hospital in East Jerusalem. Even if a patient gets a permit, which is always for a limited period of time, free passage at checkpoints is not guaranteed, and the Israeli Army can suspend or cancel a permit for security reasons. The amount of time spent waiting at checkpoints for patients who do not live in East Jerusalem is enormous and hampers the regular follow-up and treatment these patients need.

In case of emergency, it is possible to get a permit to East-Jerusalem in one day, with the help of the Palestinian Red Crescent Society, and with the agreement of the Israeli authorities; however, even ambulances are sometimes stopped and searched at the checkpoint, which significantly increases the travel time to the hospital and may therefore endanger the life of the patient. Moreover, in case of Jewish holydays or in cases of security alerts, some checkpoints are purely and simply closed. In such cases, the permits to go to East Jerusalem are no longer valid; if a medical operation was planned this day, it is canceled and postponed until the reopening of the checkpoints.

In Gaza, the blockade has had severe consequences on the health of the inhabitants; in the absence of some specialized health services, many patients are redirected to East-Jerusalem when the local infrastructures are unable to provide a good treatment, causing delays of treatment and a potential worsening of their health. These redirections have to be approved by the Israeli authorities, which can refuse or delay it. In 2010, a bit less than 20% of these applications were either delayed or refused

; it may be referred to as a denial of an appropriate medical treatment which can severely endanger the life of the patient. The blockade on Gaza has severe consequences on the health of Palestinians, as Gaza does not have the specialized infrastructures needed to treat all patients; many of them have to be transferred to East Jerusalem to be treated, causing delays of treatment and a potential worsening of their health.

III) Blockades and other obstacles, a hindrance to the well-functioning of medical facilities

The restriction on movements in the oPt acts on the two sides of health services: the medical staff from the one hand, the patient from the other hand.

To run properly, a hospital requires various qualified health professionals, such as doctors, but also nurses, auxiliary nurses, qualified technicians to run the medical equipment, etc. This medical staff is also affected by the presence of checkpoints; they also have to go through the blockades and the Wall of the West Bank.

Because of the restriction on movements, frequent delays of the medical staff are observed. The checkpoints cause doctors, nurses and other health professionals to be often late, or unable to reach their place of work, although their presence is obviously necessary to run the hospital. According to Physicians for Human Rights Israel, around 70% of the medical staff operating in the Palestinian hospitals of East Jerusalem lived in the West Bank or in the Gaza Strip.

The recurrent absence of doctors in medical facilities, because of the delay that doctors often have to endure, or because of the simple denial of access of some doctors to some remote communities, is one of the most important factors of the difficulties encountered by Palestinians regarding health. The absence of these professionals causes either delays of treatments, or the pure and simple unavailability of some essential services for patients.

Doctors have theoretically an easier access through the checkpoints; the other medical staff of the hospitals is supposedly also not delayed at the checkpoints, but this system has numerous flaws, and there are daily cases of either delay or denial of access to East-Jerusalem of doctors, nurses, or auxiliary nurses. For the rest of the West Bank, doctors do generally have a special access through checkpoints, but cases of denials of access or long delays are extremely frequent. The chronic lateness of staff sometimes questions the well functioning of the hospital, and the development of an efficient and trustworthy health sector in the West Bank. An example perfectly illustrates this consequence of the Segregation Wall: according to CARE, 75 to 80% of medical facilities who experienced the suspension of the availability of some services argued that the main reason for the suspension was the inability of skilled members of the staff to reach the medical unit, because of the closure of some checkpoints or because of a curfew imposed by the Israeli administration.

The Physicians for Human Rights and the Health, Development, Information and Policy Institute (HDPI) reported cases where ambulances which were carrying a patient to a hospital in East Jerusalem were denied access at the checkpoint and asked to go back. The OCHA reported that in the month of July, 2007, 40 ambulances were not allowed to go though the checkpoints to access patients in the West Bank.

The Palestinian Red Crescent society reported 440 cases of ambulances either delayed or denied access in the oPt in 2009, with almost 70% of these cases concerning checkpoints to East Jerusalem. This figure shows that denials of access are not exceptions and occur quite frequently in the oPt.

Similarly, the training of medical students is another matter; some medical specialties are only available in East-Jerusalem; thus, they need a permit to access these hospitals; some students were reported to have to stop their medical training because of the refusal of the Israeli authorities to grant or renew the permit of these medical students. Although quite rare, this denial of access severely infringes upon their rights to a proper training and career choices.

The problem of denial of access or delays is experienced by both the medical staff and the patients. In 2005, a representative of the Palestinian Red Crescent Society said that 200,000 Palestinians were already being denied free and open access to healthcare because of the Wall.

Mdecins du Monde, a non-governmental humanitarian aid association, which runs clinics in the West Bank, reported that in 2003, 28.7% of women in Mdecins du monde and Health Work Committee (HWC) clinics have been prevented from going to hospital for delivery by closures and curfews.

[ Therefore, some Palestinians women have resorted to midwives, to deliver at home, although it cannot provide the same level of safety than an equipped hospital in case of medical complications.

The restriction on movement also plays on a different, more indirect level: as the travel times to reach medical facilities increased significantly with the construction of the Wall, patients requiring medical consultations or treatments may be totally discouraged to go to the hospital, and cancel or delay the visit. In this period, their health condition may deteriorate, and the treatment may not be as effective. Similarly, the restriction on movements and the great amount of time needed to reach an adapted medical facility also encourages self-medication, with potentially severe consequences on health if the drugs taken are not appropriate, either in type or in quantity.

Palestinians from the West Bank also complain not to have access to regular medical check-ups and therefore to the early detection of infectious disease, cancer or other types of affections, for which an early detection often leads to a rapid recovery. If patients want to reach a hospital in East Jerusalem, they can rarely do so in case of emergency. Getting a permit to be treated in Jerusalem is possible, but only after long procedures; the permits delivered to be treated in hospitals in East Jerusalem are often planned in advance. According to Mdecins du Monde, in 2003, 56,755 permits were issued in the West Bank for a population of about 2,313,609.

As we have seen, the restriction on movement has disastrous consequences over the health of Palestinian patients, but it has also severe significant consequences for hospitals. To access a hospital in East Jerusalem for an inhabitant of the West Bank and Gaza, a special permit is necessary; to get it requires long administrative steps. Therefore, East Jerusalem hospitals, which used to receive many patients from the rest of the West Bank and Gaza, have suffered from a strong decrease in the number of patients they treated. Economically, they have suffered heavily; from 2002 to 2003, the number of outpatients from the West Bank and Gaza Strip in East Jerusalem hospitals dropped by almost 50%. The occupancy rates of beds in these hospitals (11% of total hospital beds for the West Bank and Gaza Strip) declined because of the construction of the Wall.

IV) The dramatic case of the Seam Zone, an eloquent illustration of the dangerous consequences of isolation

The Seam Zone (between the Green line and the Israeli Wall), has few health infrastructures. According to the United Nations office for the coordination of humanitarian affairs (OCHA), approximately 33,000 Palestinians holding West Bank ID cards in 36 communities will be located between the Wall and the Green Line, once the Wall is completed.

The Seam Zone is considered by Israeli authorities as a closed military area; visitors who wish to go there do need to apply for a permit, before being allowed to enter. The official military order stipulates that no one will enter the Seam Zone, and no one will remain there. Similarly, inhabitants aged 16 or above have to apply to get a permanent resident permit from the Israeli authorities, to keep on living on the land they own. For others, such as visitors, a specific reason is required to apply for a temporary permit. To exit these areas, Palestinians have to go through a checkpoint, controlled by Israeli soldiers, and they are usually allowed to go through only at a specific checkpoint. 78 Palestinian villages are located behind the Wall, therefore isolated from the rest of the West Bank.

Map 3: The Segregation Wall in the West Bank

On map 3, we can see the areas isolated between the Wall and the Green line, in the West Bank.

In the absence of sufficient and adapted health infrastructures in the Seam Zone, going through a checkpoint or a Wall is necessary to get a medical treatment; however, only two of the 13 checkpoints which controlled the Seam Zone in 2004 were open continuously; the eleven others being open several times (usually only two or three times) during the day

. In case of emergency, farmers in the Seam Zone may be trapped within the Zone and not have access to health care. In case of work accidents in the Seam Zone, or another event requiring immediate medical intervention, the situation remains the same, except if a military patrol notices the accident.

Moreover, the restriction of vehicles inside the Seam Zone prevents farmers from transporting the person requiring medical care in a motorized vehicle; donkeys, horses or tractors are often used, which may enhance the danger on the patients life. Similarly, doctors and ambulances from the outside cannot access the Seam Zone and provide emergency medical care even in cases of serious injuries.

The security Wall, as it physically separates the inhabitants of the Seam Zone from medical centers, violates the right to health of residents of the Seam Zone, as the access to adapted medical units when needed is compromised except when the checkpoint is open. On the same level, the fact that doctors and ambulances cannot enter the Seam Zone without permit leaves the inhabitants of the Zone completely devoid of adapted medical care. When the checkpoints are closed, at night, inhabitants of the Seam Zone cannot access emergency care at all and have sometimes to wait for hours before any treatment is possible, which very severely endangers the life of patients who need such rapid medical treatment.

Therefore, in case of emergency, sick people may see their life threatened by the lack of appropriate medical infrastructures. Some checkpoints in the Seam Zone are entirely closed at night: it was notably the case of the Azzun Atma checkpoint, which was closed, until March 2010, from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m., thus preventing any people from leaving the area for night hours. In the village itself, there was only one medical unit, i.e. a primary health care unit, which was open four hours a week; It encouraged pregnant women, who lived there, to pass the checkpoints days, sometimes weeks, before the expected date of birth, in order not to be blocked at the checkpoint in case of early delivery. This imposes a kind of curfew to the population and denies the right to be treated in case of emergency, effectively endangering the lives of the inhabitants. This example eloquently shows the risks posed by the security Wall on the health of inhabitants of the West Bank (or at least in some regions of it).

V) The difficult distribution of medical facilities in the oPt

The shortage of basic medicine supplies is another example of the way the Israeli closures undermine the development of the Palestinian health sector. The restriction of the movement of goods leads to recurrent shortages of certain drugs in pharmacies of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The distribution from the drug manufacturers to the pharmacies is restricted by the Israeli closures and goes at a much slower pace than it would without restrictions. The areas suffering the most from Israeli closures have to cope with frequent shortage of drugs.

For example, the regional office of WHO for the Easter Mediterranean region (WHO EMRO) reports that in the Ministry of Healths Gaza Central Drug Store (CDS), which supplies the ministry of health hospitals and clinics in the Gaza Strip, of the 480 medications on the essential drug list, 178 (37%) were reported at zero stock levels at the end of May 2011.

These shortages have detrimental consequences on the health of Palestinians: in the absence of the needed medication, their health condition may deteriorate and provoke medical complications which could have been avoided. These shortages encourage people to try new stores and pharmacies, which may provide inappropriate treatment or doses. Patients with chronic diseases do have greater risks. As for them, hospitals had to reschedule operations which could not be performed because of the lack of the appropriate drug or a shortage of necessary disposables. The gravest cases, even if they normally could have been treated in Gaza, had to be transferred outside of the Gaza Strip, because shortages made the necessary operations impossible. The WHO office for the Eastern Mediterranean also reports that shortages of essential drugs are chronic in Gaza since January 2011.

The blockade of Gaza also led to a grave deterioration of health conditions in the Gaza Strip; while in 2006, 382 cases were referred to East Jerusalem from the Gaza strip, this number was multiplied more than eight times in 2008, to reach 3118 patients.

The transportation of drugs from the drug manufacturer or distributor to the medical facilities is often a major problem and results in an unavailability of some drugs in some pharmacies, often in small villages. This contributes to hamper the development of the health system in the oPt.

In the refugee camps, doctors are extremely rare; in the Dheisheh refugee camp, south of Bethlehem, where 13000 persons live; there is only one part-time doctor. This gives a glimpse of the health situation in the West Bank, and how restrictions on movements have contributed to slow the development of the health sector.

Generally, Palestinians of the oPt show a great concern regarding the need for emergency treatments. Indeed, there are not ambulances in every village; to reach some villages, ambulances, even if they usually (but not always) benefit from a priority access through checkpoints, need a long time (sometimes several hours), because of the detours they have to make and because the 630 blockades in the West Bank greatly increase the average transportation time. Critical cases, which would need medical care as early as possible, sometimes have to wait hours before the ambulance can reach first the village, then the hospital.

The World Bank denounces the deterioration of the primary healthcare network in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The restriction on movements, both of goods and of people, takes a significant share of responsibility in this deterioration; shortages of medical supplies are quite common, and sometimes concern elementary pills.

Another problem concerns the availability of laboratory tests in the clinics isolated by the Wall (26 of them were identified in 2004), in the West Bank. Basic tests, such as blood glucose, or urine analysis, were possible in only half of the clinics isolated by the Wall, while this is a necessary element for a trustworthy diagnosis. More advanced laboratory tests were available in only two clinics, meaning that 24 clinics were deprived of the possibility to run complex tests.

Lab tests have become a necessary tool to be able to provide a tailored treatment to the patient. In the absence of such tests, the treatment might not be adapted to patients.

VI) Indirect consequences of the restriction of movements: isolation, economic slowdown & their outcomes

As a corollary of the blockade, the economic situation in Gaza over the past few years has deteriorated; yet, economic growth and enrichment of the population often leads to the development of the health sector. The restriction on movement, which damaged economic growth, has therefore an indirect effect on development of the health sector. The restriction on movements limits the potential growth of the oPt, and the Gaza strip in particular has to face severe economic hardships. As the WHO specialized Health Mission in Gaza reported, because of the blockade, The economic and social conditions for the civilian population have deteriorated, with increasing poverty and almost total dependency on external aid, leading to a worsening of the health conditions of the population.

The gross domestic product per capita in 2007 represented only 60% of what it was in 1999, which shows the scale of the Palestinian economic recession. Because of this recession, the tax revenues decrease which limits the room for maneuver for the government and the potential development of the health sector.

Many people do not have health insurance and have to pay all their health expenditures in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. 22% of people are not insured at all, 19% are entitled to free health insurance, provided by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency. 40% of total Health expenditures in oPt are out-of-pocket expenditures, which contribute to the impoverishment of the population; according to World Bank data of 2005, 13,7% of households are considered poor before payments of healthcare expenditures, 25% are considered poor after these payments.

Therefore, some patients try to avoid medical consultations as often as possible. This contributes to the deterioration of the health of Palestinians.

The deep poverty level in Gaza, caused, among others, by the Israeli blockade, reached 35% of the population in 2007; as the health of the population is partially dependent on the wealth of its inhabitants, this deep poverty contributes to the deterioration of the health system. The impoverishment of the population tends to be detrimental to the overall health situation in the oPt.

In 2004, half a million Palestinians were completely dependent on food aid; 60% of the Palestinian population lived with less than US$ 2.1 a day.

High levels of poverty and dependency to humanitarian aid represent a threat to the national systems of health.

Because of the closure, the consumption of water between Israelis and Palestinians differs greatly: on average, an Israeli consumes five times more water than a Palestinian. Palestinians have a water supply of approximately 75 liters/per capita/per day.

In 2004, 15% of clinics isolated by the Wall had no running water, which eloquently shows the consequences of the building of the Wall and the resulting restriction on the state of the health sector in the West Bank. Electricity is another problem: in clinics isolated by the Wall, electricity very often worked only for working hours. The lack of a trustworthy, permanent electricity supply is a tragedy for hospitals, especially concerning pills and vaccines which have to maintain the cold chain.

The lack of electricity supply also prevents the use of medical equipment.

Similarly, frequent electricity cuts, may endanger the life of patients or prevent effective and appropriate medical care to patients. In Gaza in particular, there are often shortages of elementary drugs, which are absolutely essential to treat patients correctly. Finally, the medical equipment lacks regular maintenance and tends therefore to deteriorate. These various challenges contribute to undermine the development of the health sector in the oPt.

Mental health is also severely affected by the blockade in Gaza and by the checkpoints. The blockade in Gaza, which lasts since June 2007, created what John Holmes, United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, an open-air prison, resulting in numerous mental disorders.

A study from the Palestinian counseling center in 2004 presented extremely worrying figures among Palestinians in the oPt: 52% of those questioned reported having thought of ending their life, 92% felt no hope for the future, 100% reported feeling stressed, and 84% expressed feelings of constant anger because of circumstances beyond their control.

VII) Conclusion: severe violations of the right to health

In spite of these difficulties, the health system in the West Bank and Gaza remains in a correct situation; it functions relatively well and provides generally good treatments to the population. The oPt health system performs better than the health systems of most Arab countries of the region, but the standards remain far from Israeli ones.

The quality of service used to be high a few years ago; even if the situation today has not become disastrous, the construction of the Wall and the restriction on movements, both in the West Bank and in the Gaza Strip, has undoubtedly led to the deterioration of the health care system. Most Palestinians still have an access to health care, although sometimes difficult and in any case much harder than before the construction of the Wall.

These policies of restrictions on movements violate several texts of International Law. The preamble of the Constitution of the World Health Organization in 1948 affirmed that the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of Health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being, without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition. Furthermore, the universal declaration of human rights of 1948, affirmed in its article 25, that everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services

Moreover, in 1966, the International Covenant on economic, social and cultural rights of 1966, ratified by Israel in 1991, went further, as it specified in the article 12.2 that the steps to be taken by the States Parties to the present Covenant to achieve the full realization of this right shall include those necessary for: (d) the creation of conditions which would assure to all medical service and medical attention in the event of sickness. This covenant was deemed applicable by the ICJ in its advisory opinion of July 2004. As we can see, Israel infringes upon the right to health of Palestinian people in the oPt. The ICJ also called for the dismantlement of the Wall in its advisory opinion of 2004. The United Nations General Assembly issued a resolution the 20th of July 2004, calling on Israel to comply with its legal obligations as identified in the advisory opinionâ. i.e. tear down the Wall and pay reparations to Palestinians for the damages provoked by the construction of the Wall, among others.

The violations of the right to Health have been repeatedly recognized by the World Health Organization; last May, the World Health Assembly expressed its deep concern at the grave implication of the Wall on the accessibility and quality of medical services received by the Palestinian population in the occupied Palestinian territory, including East Jerusalem.

The Israelis claim that they built the Wall for security reasons, to protect Israeli citizens from what they call terrorist attacks. But the Palestinian see the Israeli Wall construction to be another procedure to grab more of the Palestinian land; especially that the Wall is routed inside the West Bank and not on the 1949 Armistice Line (the Green Line), which defines the West Bank borders. Hence, reference to security is a double-edged sword: indeed, security for Palestinians has been severely undermined by the restriction on movement, which poses a threat to Palestinians health; and their existence on the land for that matter. The Israelis has undoubtedly the right to protect its citizens but the settlements and the settlers in the West Bank stand in violation of the international law and to the UN resolution and the ICJ ruling; thus Israel has the obligation to respect international Law and the Health of the population of the lands it occupies.

Bibliography

-

Health, Development, Information and Policy Institute (HDIP), Health and Segregation:

the impact of the Israeli Segregation Wall on access to health care services, Ramallah, 2004

-

-

-

EKLUND L., Accessibility to Health Services in the West Bank, Occupied Palestinian Territory, (ARIJ, 2010).

-

-

-

-

-

-

Health Nutrition and population, World Bank,

Who pays ? Out-of-pocket health spending and equity

implications in the Middle East and North Africa, November 2010.

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/HEALTHNUTRITIONANDPOPULATION/Resources/281627-1095698140167/WhoPays.pdf

-

-

-

INTEGRATED REGIONAL INFORMATION NETWORK (IRIN),

OPT: Cut off from healthcare, 2 May 2011.

http://unispal.un.org/UNISPAL.NSF/0/2D2FAB12783AED0085257884004D45CE

-

-

-

-

-

Definitions: Mosby Medical dictionary, online version

[1] EKLUND L., Accessibility to Health Services in the West Bank,

Occupied Palestinian Territory, 2010

[3] Office for the coordination of humanitarian affairs occupied Palestinian territories

and World Health Organization, the impact of the Barrier on Health, July 2010

[4] EKLUND L., Accessibility to Health Services in the West Bank,

Occupied Palestinian Territory, 2010.

[5] EKLUND L., Accessibility to Health Services in the West Bank,

Occupied Palestinian Territory, 2010

[6] Médecins du monde, The Ultimate Barrier:Impact of the Wall on the

Palestinian health care system, February 2005

[7] COHEN D, Barrier in West Bank threatens residents’ health care, says report,

British Medical journal, 19th February 2005

[8] Health, Development, Information and Policy Institute (HDIP), Health and Segregation:

the impact of the Israeli separation Wall on access to health care services, 2004

[9] Médecins du monde, The Ultimate Barrier:Impact of the Wall on the

Palestinian health care system, February 2005.

[10] United Nations news center, More Palestinians die after being denied access through

Israeli checkpoints, UN reports, 28 September 2007

[11] Office for the coordination of humanitarian affairs occupied Palestinian territories and

World Health Organization, the impact of the Barrier on Health, July 2010

[12] WHO, The occupied Palestinian territory: providing health care despite

the lack of a stable environment, Monthly Highlights, February 2011

[13] Habib I., A Wall in the Heart, Physicians for Human Rights Israel, 2005.

[14] Health, Development, Information and Policy Institute (HDIP), Health and Segregation:

the impact of the Israeli separation Wall on access to health care services, 2004

[15] Matari A.a, Khatib R., Donaldson C. et alii, The health-care system: an assessment and

reform agenda, Lancet 2009

[16] BBC News, Middle East, Barrier ‘harms West Bank health’, February 15th, 2005.

[17] Médecins du monde, The Ultimate Barrier:Impact of the Wall on the

Palestinian health care system, February 2005.

[18] Health, Development, Information and Policy Institute (HDIP), Health and Segregation:

the impact of the Israeli separation Wall on access to health care services, 2004

[19] Regional office for the Eastern Mediterranean, WHO, Shortages of Drugs and

Medical Disposables in MoH Gaza, June 2011

[20] IRIN, OPT: Cut off from healthcare, 2 May 2011

[21] Health, Development, Information and Policy Institute (HDIP), Health and Segregation:

the impact of the Israeli separation Wall on access to health care services, 2004

[22] WHO Specialized Health Mission to the Gaza strip, Extended report, Ge,neva 21 May 2009

[23] Health Nutrition and population, World Bank, Who pays ? Out-of-pocket health spending

and equity implications in the Middle East and North Africa, November 2010

[24] Health Nutrition and population, World Bank, Who pays ? Out-of-pocket

health spending and equity implications in the Middle East and North Africa, November 2010

[25] Health, Development, Information and Policy Institute (HDIP), Health and Segregation:

the impact of the Israeli separation Wall on access to health care services, 2004

[26] Health, Development, Information and Policy Institute (HDIP), Health and Segregation:

the impact of the Israeli separation Wall on access to health care services, 2004

[27] WHO, Country Cooperation Strategy for WHO and the occupied

Palestinian territory 2006-2008, November 2005

[28] Giacaman R, Khatib R, Shabaneh L, et al.

Health status and healthservices in

the occupied Palestinian territory, Lancet2009;

[29] WHO, Sixty-fourth World Health Assembly,

Health conditions in the occupied

Palestinian territory, including east Jerusalem, and in the

occupied Syrian Golan, 20th May 2011.

Prepared by: