In a new escalation within a systematic Judaization campaign, Israeli municipality of Jerusalem issued mass demolition orders on July 30, 2025, targeting all homes in the village of Nu’man, located northeast of Bethlehem and southeast of occupied Jerusalem. The orders affect 35 homes comprising 45 inhabited residential units. The authorities claim these structures were built without permits. The demolition orders were delivered during a raid carried out by Israeli forces accompanied by personnel from the Jerusalem Municipality, who handed the notices directly to residents.

This marks the third such wave of demolition orders in 2025 alone, following previous rounds in January and June. For over 35 years, Israel has pursued a policy that prohibits construction in the village, leading to the displacement of more than 100 residents. The current population stands at around 150, according to the village council. These measures clearly aim to forcibly depopulate the village and annex it into the jurisdiction of the Israeli-controlled Jerusalem Municipality.

Simultaneously, for the past two years, Israeli authorities have imposed retroactive property taxes (Arnona) on homes in Nu’man. This residential and commercial property tax forced residents to pay between 30,000 and 60,000 shekels per home, despite the complete absence of municipal services. This contradictory approach, where the village is included within the municipality’s boundaries yet denied the rights of municipal residents, reflects the discriminatory and exclusionary nature of Israeli policy.

Historical Background and Ongoing Suffering

In June 1967, following Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, Nu’man village was administratively (but illegally under international law) annexed to Jerusalem. However, its residents were registered as West Bank inhabitants, creating a legally ambiguous status. While the immediate impact was minimal, the full ramifications emerged after Israel’s imposition of a general closure in 1993, following the Oslo Accords. At that point, residents began to be considered “illegally present” in Jerusalem, despite living within the city’s municipal boundaries.

Since then, entry into other areas of Jerusalem has required special permits from the Israeli Civil Administration, and even remaining in their own homes has become conditional on permit approval. Meanwhile, the Jerusalem Municipality has provided no services to the village, compelling residents to rely on service providers from the West Bank.

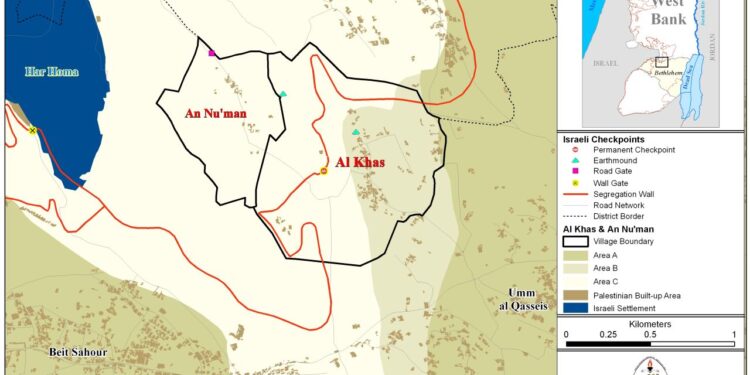

Restrictions intensified during the Second Intifada, particularly in January 2003, when Israel closed the only road connecting Nu’man to the rest of Jerusalem through Umm Tuba village. In the same year, construction of the segregation wall began east and south of the village, physically isolating it from nearby Palestinian communities such as Beit Sahour and al-Khas, and severing access to Bethlehem.

In addition, Israeli authorities confiscated agricultural lands owned by villagers to construct a settler road connecting Har Homa (Abu Ghneim) settlement with Nokdim and Tekoa settlements. The road, commonly referred to as “Lieberman Road,” is named after Avigdor Lieberman, a political figure and settler-resident of Nokdim.

In 2006, an Israeli security gate was erected at the southeastern entrance to the village, establishing a permanent checkpoint manned by Israeli Border Police. This crossing became the only access point between Nu’man and the rest of the West Bank. Only officially registered village residents and a limited number of service providers are permitted to pass; mostly on foot, while vehicular passage is restricted to those with Israeli IDs.

These cumulative restrictions have completely isolated the village, both geographically and socially. Nu’man once had sufficient economic and social ties to its surroundings in both Jerusalem and Bethlehem. These connections have weakened and eventually faded away under the weight of Israeli-imposed constraints. The village’s economy largely based on agriculture and livestock has collapsed due to Israeli restrictions.

Lack of Services and Basic Life Essentials

Nu’man lacks a health clinic or medical services. A mobile UNRWA clinic used to visit weekly before the wall was built, but Israeli authorities have since barred its entry. As a result, residents must walk approximately 1.5 kilometers to reach the checkpoint, and then travel by another vehicle to access medical care in Beit Sahour or Bethlehem hospitals.

The village also has no school. Children must walk about two kilometers through rough territory to attend schools in nearby al-Khas and al-Ubeidiya. Students are often subjected to searches on their way home by the Israeli soldiers at the checkpoint, thus imposing a daily psychological burden on them causing a number of them to call upon their parents change residency, which is what Israel ultimately wants.

These limitations extend beyond services to affect family and social structure. Visiting relatives face difficulty entering the village, even during religious holidays, weddings, or funerals, deepening the community’s isolation.

Legal Struggles and Israeli Evasion

In 2004, village residents petitioned the Israeli Supreme Court to either dismantle the segment of the segregation wall surrounding Nu’man or recognize them as official Jerusalem residents by granting them Israeli ID cards. An agreement was reached to maintain the wall while establishing a committee to review the villagers’ legal status. However, this committee was never formed, and no progress was made.

In 2006, the municipality demolished two homes housing 13 individuals, citing “unlicensed construction.” These demolitions occurred despite the municipality’s refusal to provide services, approve building plans, or collect taxes from the residents, exposing the demolition orders as a tool for systematic displacement.

After the failure of the initial agreement, residents submitted a new petition in 2007 requesting either the wall’s removal or legal residency status, along with the provision of basic services and freedom of movement. This petition remains unresolved in Israeli courts, while the suffering continues unchanged.

Conclusion: Nu’man as a Case Study in Displacement and Demographic Manipulation

The policies targeting Nu’man, including demolition, displacement, and economic suffocation, form part of a broader colonial expansion project aimed at annexing land and severing East Jerusalem from its Palestinian surroundings and natural environment. The situation in Nu’man illustrates a deliberate strategy of forced demographic and geographic transformation, executed in blatant disregard for international law and humanitarian standards.

This is occurring in parallel with aggressive efforts by the Israeli Municipality of Jerusalem to expand the nearby Har Homa (Abu Ghneim) settlement. These expansion plans include construction on land privately owned by Nu’man residents, underscoring the broader aim of territorial consolidation and Palestinian eradication.

Prepared by:

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem