1. Abstract

This brief provides scrupulous analyses of one of the latest chapters of the prolonged Israeli colonial project in the occupied city of Jerusalem. The analyses provide a critical view from a Palestinian planning perspective, using an in-depth mapping approach of Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Systems, as well as a thorough study of relevant archived research. The scene-setting prelude of this brief will cover the delineation of de facto Israeli administrative changes of the Jerusalem city boundaries from the 1947 “Corpus Seperatum” through the 1967 “new municipal boundaries” that 10 folded the original size of the city, ending with the 2005 “Jerusalem 2020 Master-plan” and the 2008 “Jerusalem District Master-plan”. The brief will, also shed light on the “shadow” or “silent” urban research in the Israeli’s colonial project that antitheses the sustainable development of civilian city of Jerusalem. The results of this brief-study show the negative impacts of favouring political tendencies over rational social, economical, and environmental ones that usually leads to sustainable solutions.

2. Background.

Following the 1967 war, the Israeli authorities declared Jerusalem city as its “eternal unified capital,” and succeeded since after in altering the geographic and demographic layout of the city and made tremendous strides in promoting their actions as a legitimate part of the democratic governing of the city. This has been achieved using a de jure policy of fluid city boundaries. The “artificially created” Green Line, Israel’s internationally recognized 1949 border, was deeply repressed, as the Jerusalem boundaries became fluid and elastic to insure a Jewish superiority, achieving the Zionist myth of “a land without people for a people without land.” This, in turn, blurred and gerrymandered the difference between “the political space of the state and the cultural space of the nation” a difference hidden by the hyphenated concept of “nation-state” (Kemp, 2000).

3. Chrono-logical Changing of Boundaries

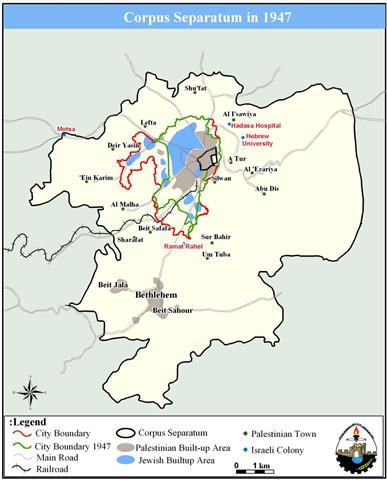

In the period 1948-1967, Jerusalem was to remain separate under international supervision, a 'Corpus Seperatum' in the words of the United Nations (UN) (See Map 1). In November, 1947, the United Nation General Assembly (UNGA), in its 128th plenary session, passed Resolution 181 partitioning Palestine into two states, one for Jewish and the other to Arab. The Arab-Palestinians rejected the plan as it confiscated 52.5% of what they owned from Mandate Palestine. The Jews who owned only 6% of the land were allocated 55.5% against 44.5% to the Arabs who owned 94% of the land. However, because of 1948 War, Israel conquest ran on 78% of Mandate Palestine, and destroyed 419 Palestinian villages in the process and created at the time the exodus of more than 900,000 Palestinian refugees (Issac et. al., 2008).

Map 1: Proposed Boundary for Jerusalem City according to Resolution 181 (II) of the UN General Assembly of 1947

Jerusalem as the sacred city for the three monotheistic religions kept drawing the attention of the world over the last forty-one years, since the Israelis occupied it after the 1967 war. Since after, the city was divided into two parts, the Jewish West Jerusalem and the occupied Arab East Jerusalem. In order to make Jerusalem the country's largest city, the Israelis redrew the administrative boundaries of the Palestinians Governorates, expanding the Jerusalem municipal boundaries from 6.5 km2 (including the old city) to 71 km2 (ARIJ-GIS Database, 2008) (See Map 2).

Map 2: The Unilateral Changes on Jerusalem Boundary Prior and After the Israel Occupation (1947-2005)

The new boundaries of the city were delineated for security reasons and demographic considerations; to create a geographic integrity and demographic superiority to Jews in Jerusalem. (Cohen 1993, p. 78) points out that the placement of the new boundary line: “was determined according to strategic-demographic policy and not according to pure planning considerations. The interest of this policy was to include within the city ridges and sites which provided strategic control of the city and the roads leading to it, along with large additional territories containing a minimum Arab population.”

For that, the expansion of the Jerusalem municipal boundary excluded the densely Palestinian communities (the residence but not the lands) in the North including Beit Iksa and Beir Nabala, where the sparsely populated communities’ lands in the south were included (Bethlehem and Beit Sahour)

However, the municipal planning deliberations were of secondary importance in setting the new boundaries.

In 2004, the Israeli Jerusalem Municipality disclosed Town Planning Scheme of 2000 that will serve till the year 2020. Accordingly, the boundary of the western part of the city is extended by 40% and the total area of the city is quadrille (i.e. 142 km2). According to the new master-plan, more than half of the eastern part of Jerusalem city is zoned as built-up areas and 24.4% is zoned as open “green natural” areas (ARIJ GIS-Database, 2008).

A new chapter of the Israeli colonial politics in Jerusalem city is the Jerusalem District Plan (30/1) that was disclosed in September 2008. The Plan accentuate on achieving the Zionist dream of a “unified” Jerusalem capital; as Jerusalem city is extracted from the milieu of the West Bank and consequently entrenching the land of Palestine in a state of “neither two states nor one,” framing a process coined by the Israeli geographer Oren Yiftachel by a “creeping apartheid” (Yiftachel, 2005). This Plan comes after five decades from the last regional plan for Jerusalem that was prepared by the British planner Kendel and named after him. The plan is also known under the name RJ5 (Coon, 1992). However, this plan was not finalized and was lost during the 1948 war.

4. Research Methodology

The adopted research methodology in this brief-study is built through deliberations on the available data sources in the forms of literature reviews, published reports, and mapping interpretations using the state-art-technology of Remote Sensing & Geographic Information Systems (GIS).

Acknowledging discrepancies is very important when planning in an occupied territory like the OPT. The contemporary architecture and urban theories developed many interesting approaches to the problem of coping with such conditions. Increasingly, one could notice a shift on interest from complexity and contradiction (Venturi, 1966), to interests in accumulation of elements (Rowe and Koetter, 1978).

In our case, using the GIS as an analytical planning tool provided the researchers with the needed flexibility to embark on an in-depth research, where different geographic layers are considered to set the base for research that generated pejorative experiencing of landscape.

Map 3: Jerusalem District Plan (2008)

5. Definition of the Master PlanThe plan is 655,526 dunums in area (ARIJ, GIS-Database, 2009). About 55% of this area is zoned of green scenery (See Table 1 & Map 4); this includes mountain reserves, agricultural areas, nature reserves, public parks, and forests. In natural circumstances, this will present a balance to the exponential population growth in a metropolitan or megacity, as in the case of Jerusalem. The proposed boundary for Jerusalem district encompasses more than 1,200,000 inhabitants (84% Jews and 16% Arabs) (PCBS 2009; ICBS 2007). According to the current population growth and the ways in which the Israeli and the Palestinian neighborhood are expanding, it is expected that the population projection within the proposed boundary of the Jerusalem district plan will climb to 2,000,000 by 2020, assuming a population growth of 3.5% per annum.

|

Table (1): Land Use Analysis of the Proposed Jerusalem District Plan |

|

|

Type |

Area (Dunums) |

|

Industrial Zone |

59 |

|

Organization / Association / Society |

361 |

|

Facilities Engineering |

603 |

|

Rural Residential Area |

670 |

|

Mountain Reserve |

1,200 |

|

1,742

|

|

|

Quarries |

3,139 |

|

Rural Residential Area at Municipal Developmental Area |

4,478 |

|

Forests for Other Purposes |

6,453 |

|

7,641

|

|

|

Joint Industrial Zone |

7,669 |

|

8,445

|

|

|

Residential Area |

11,020 |

|

Developmental Area – Residential site |

22,334 |

|

23,971

|

|

|

Agricultural Area – Rural Mountain |

27,918 |

|

Mountainous Agricultural Area |

33,218 |

|

Nature Reserve |

56,652 |

|

Developmental Area – City Center |

92,780 |

|

Developmental Areas |

145,903 |

|

Forests |

199,269 |

|

Total |

655,526 |

|

Source: ARIJ GIS-Database, 2009 |

|

Map 4: Land-Use & Land Cover of the Jerusalem District Plan

6. State Borders and Right of Return

The plan set its border as a consolidation to the unilateral and illegal Israeli Jerusalem municipal boundary of 1967. However, the plan extends to the western parts ending with a non-symmetric figure.

Israel after 1948 acquired control over the Arab properties in West Jerusalem that calculates about 40 percent of the city’s total area (Halper, 2000) by virtue of the Absentee’s Property Law of the year 1950, where the Arabs were banned from their properties after being driven out in 1948. Paradoxically, the Jews who “lost” their properties after 1948 in East Jerusalem were permitted under Israeli law after 1967 to take back their properties or receive an appropriate compensation. In the meanwhile, the Israeli occupation authorities after 1967 activated the British Mandate Land Ordinance to expropriate around 85% of the lands included within the illegally expanded East Jerusalem area (Issac et. al., 2007), leaving no space for needed future natural expansion and for the indigenous Palestinian communities to cope with their natural population growth.

Map 5: Sprawl of Jewish Settlements in Western Suburbsof Jerusalem before and after the 1948 War

To close this argument, the plan entails the consolidation to the illegal confiscation of the Arab properties and land rights by the Israeli authorities in the western suburbs of Jerusalem. Thus, the plan put an end to the Palestinian aspirations of the right to return to their home lands. By, refuting the right to return of Palestinians to their homelands and confiscated properties inside today-Israel, the plan contribute to what Mick Dumper (2008) call the “Constructive Ambiguity” that framed the Israeli de facto policies since its occupation of the OPT. Therefore, the Plan simply proposes tacitly to refute the international humanitarian law and the pertinent United Nations General Assembly Resolution (UNGA) 194 of 1949, as the base for reconciliation between the Israelis and Palestinians.

7. Geo-demography: Israeli Settlements

The Israeli policy in Jerusalem area through the prolonged 41 years of occupation aimed at keeping the demographic supremacy to their favour. However, this supremacy “anthropogenic population growth” represents only the fake face of reality, simply because it encourages Jewish growth while confining Palestinian growth within the city and beyond its hinterlands. The Israeli physical domination in Jerusalem was implemented through thoroughly enacted policies to establish irreversible and exclusive control over land and its resources by confiscating and razing lands, erecting and expanding illegal Israeli settlements, paving bypass roads, destroying Palestinian houses, and now building the Separation Wall in and around East Jerusalem. This part will briefly discuss the “geo-demographical outlook” (Issac et. al., 2008) of the Jerusalem District Plan, which is invoked in the building of the illegal Israeli settlements east of the Green Line (1949 Armistice Line).

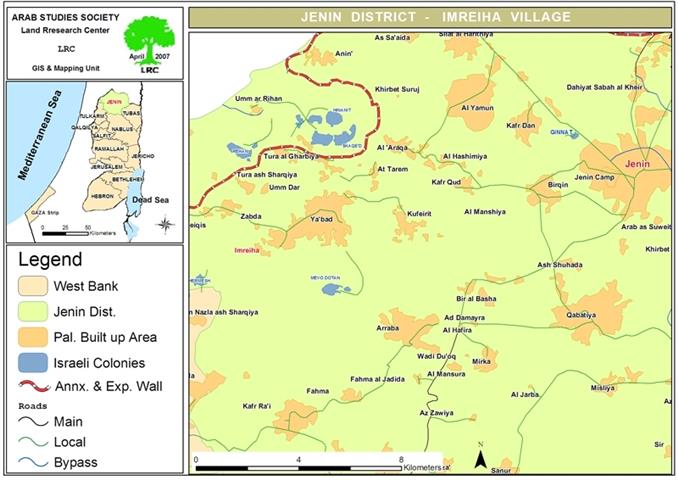

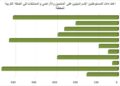

The first Israeli settlement in Jerusalem was inside the Old City immediately following the 1967 War, when the Israeli Army destroyed more than 700 buildings to expand the Jewish quarter. Throughout the years of occupation, Israeli colonies mushroomed inside the Israeli defined municipal boundary of Jerusalem and the surrounding area. The settlements in Jerusalem may be classified by administrative association as settlements inside the municipal boundary (in J1 area), and settlements within Jerusalem Governorate (J2 area), and they count 18 settlements. Additionally, Israeli settler organizations are infiltrating and initiating settlement cores in the hearts of Palestinian neighborhoods, such as the settlement in Al- Sheikh Jarrah around Shimon Ha Zadik and the settlement core in Silwan, Al -Tur and Ras Al-Ammoud (ARIJ, 2007).

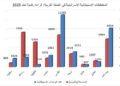

Israel hasn’t desisted from its colonial expansion program anytime since the signing of the Oslo Accords. In fact, Israel has adopted a more intense approach to developing settlements in Jerusalem. This has resulted in an increase of settlements areas between 1996 (25,069 Dunums) and 2005 (44,684 Dunums) of 78% (i.e. 19615 Dunums), which reflects Israeli plans to maintain dominance over Jerusalem by means of creating facts on the ground that will make the Jewish presence in occupied East Jerusalem an irrefutable fact. Plans are also prepared for large annexations to existing settlements. These may be considered new settlements of their own and are located near Har Homa (1,080 Dunums) and near Ma’ale Adumim; this is known as the E1 plan and will confiscate 12,500 Dunums from nearby Palestinian villages.

As the plan, secure the de facto annexation of the Israeli settlements east of the green line it desists with its colonial demographic engineering, in order to remain Jewish supremacy. That is, the settlements that percolate east of the green line and inside the Jerusalem District Plan occupy an area of 21, 026 dunums (21.026 Km²) with an estimated settler’s population of 195,000 (ARIJ GIS-Database, 2009).

Map 6: Population Distribution within the proposed Jerusalem District Plan

8. Ecological Landscape

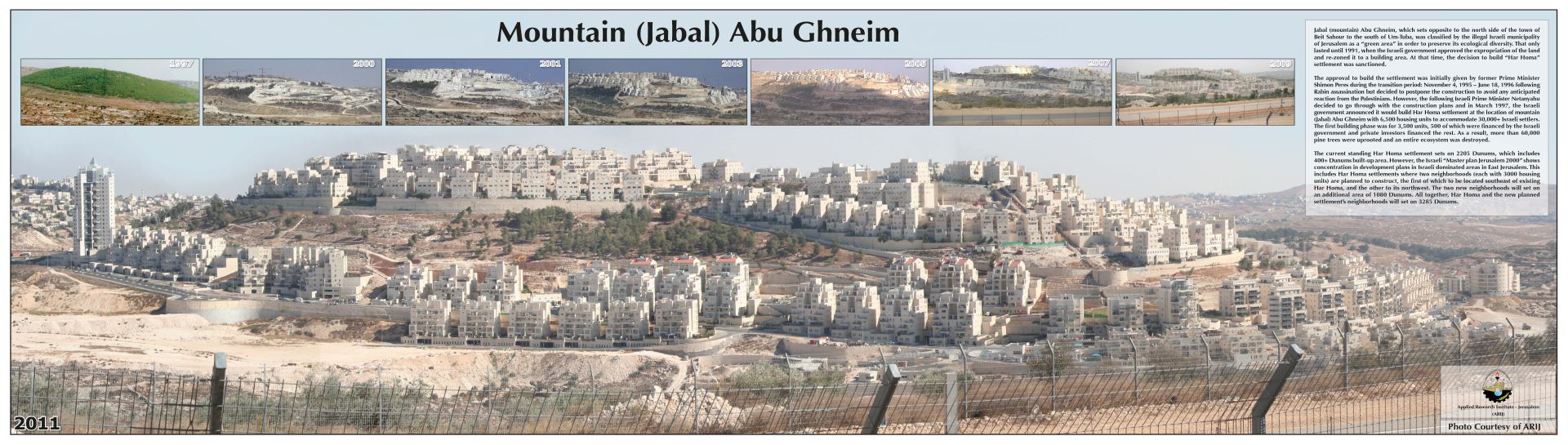

The new plan defines more than 50% of its area as of green scenery. The empirical evidences have proved that the Israeli authorities appropriate such areas for colonial purposes rather than for sustainable solutions. This manipulation of land-use within the plan contributes to the developed theory of “agoraphobia; the fear of space” (Salmon, 2002) that was articulated by Christian Salmon, where he outlines that the crux of the Israeli colonial politics relays not only on the division of territory but its abolition. The Israeli Jerusalem Municipality as-though legal maneuver of designating Palestinian lands into “green natural” zones only help them to gain time to strategically abolish the landscape by its concretization with illegal exclusive Jewish settlements, such as Har Homa Settlement that was built on Jabel Abu Ghneim south of Bethlehem (See Photo 1).

Photo 1: Concretization of Jabal Abu Ghneim

9. Infrastructure Warfar

Israeli authority utilized both social and physical engineering policies to de-develop the Palestinian communities in the city of Jerusalem. The social policies are epitomized, but not limited to the adopted policy of demographic engineering in the city and its environs. However, a loud aspect of warfare in the city is the physical destruction and construction of infrastructure and its inadequate supply. Infrastructural networks – because of the ways in which they connect, bind, and enable life and movement – become essential targets and potential instruments of Israeli war (e.g., Graham 2002, 2004). They can bypass and exclude (and thus cut off and destroy) as well as provide opportunities for connection and choice (Salamanca, 2007). The city of Jerusalem provides a powerful case in this context, especially because it is ruled according to municipal regulations rather than military ordinances like the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The construction of infrastructural networks here seems to serve not only as a source of connection, but also as a means of nationalist division, discrimination and control (see e.g., Falah and Newman, 1995; Yiftachel 1996; Halper 2000). At the same time, state-led infrastructural destruction by military means has led some scholars to identify Israeli policy as “de-development” (Roy, 1987), “forced de-modernization” (Graham, 2002), or “politics of creative destruction” (Salamanca, 2007).

As an example of the Israeli discrimination in infrastructure supply, the plan at hand provide one kilometer of paved road for every 3,474 persons west of the Green Line and within the proposed boundary, compared to one kilometer paved road for every 3,818 persons east of the Green Line and within the proposed boundary, this include the Israeli settlers in the eastern parts of the City, who calculate around 195,000. Furthermore, the plan provides 7,641 dunums of public garden west of the green line, where the eastern parts are totally ignored. It is worthy to notice that the Jerusalem 2020 Master-plan provided one public garden for every 447 persons in West Jerusalem compared to a garden for every 7,362 persons in the Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem. (ARIJ, GIS-Database, 2009).

10. Concluding Notes

From a Palestinian planning perspective, the Jerusalem District Plan is seen as a new chapter of the prolonged Israeli colonial project in the Jerusalem area. Since its establishment is a state, Israel has heavily relied on coercing facts on the ground, through “as though” planning procedures. Knowledge in planning was used to serve the Zionist dreams of the state of Israeli at the expenses of the indigenous population of the OPT in general, and Jerusalem in particular. Nowadays, in-depth research is hardly needed to prove the adverse impacts of the Israeli “business-as-usual” approach of planning in and around Jerusalem. The Israeli “as though” planning procedures (including the Segregation Wall, Israel settlements and Outposts, Israeli controlled roads, among others), have stifle the urban development of the Palestinian communities in Jerusalem, with the aim to facilitate the “voluntary transfer” from the occupied city. This comes in contradictions with the 'International Humanitarian Law' that obligates Occupying Powers (i.e. Israel) to protect freedom of movement for the population of any Occupied Territory (i.e. Palestine), as well as their (Population under Occupation) political, economic, cultural and social rights.

-

'Everyone lawfully within the Territory of a State shall, within that Territory, have the right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose his residence.' (Article 12.1, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (OHCHR, 1966).

To end, the Palestinian planners have to employ knowledge in planning to use it as a mean of resistance to the Israeli colonial project. Inevitably, the Palestinian concerted efforts will end with fruitful outcomes and concrete results.

11. Sources and BibliographyApplied Research Institute – Jerusalem (ARIJ), GIS Database, (2007-09).

-

Cohen, S.E. (1993), “The Politics of Planting: Israeli–Palestinian Competition for Control of Land in the Jerusalem Periphery,” pp. 78. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

-

Coon A. (1992) “Town Planning under Military Occupation”. Aldershot, UK: Dartmouth Publishing Company Limited.

-

Dumper M. (2008). “Constructive Ambiguities? Jerusalem, International Law and the Peace process.” Jerusalem Quarterly.

-

Falah, G. & Newman, D. (1995) “The spatial manifestation of threat: Israelis and Palestinians seek a ‘good’ border, Political Geography”, 14, pp. 689 – 706.

-

Graham, S. (2002) “Bulldozers and bombs: the latest Palestinian-Israeli conflict as asymmetric urbicide”, Antipode 34(4) pp. 642-49.

-

(2004) Cities, war, and terrorism; towards an urban geopolitics (Oxford: Blackwell)

-

Halper, J. (2000) “The 94 Percent Solution: A Matrix of Control”. Middle East Report, 216, pp. 14-19.

-

Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics- ICBS (2007).<http://www.cbs.gov.il/ishuvim/ishuv2006/bycode.xls>.

-

Issac J. et. al. (2007) “De-palestinization of Jerusalem”. (Unpublished).

-

(2008) “Geo-demographical outlook for Jerusalem”. First International Conference on Urban Planning in Palestine, pp. 217-242.

-

Jabary-Salamanca O. (2007), Infrastructural violence in the West Bank and Gaza Strip: the politics of creative destruction. PhD research proposal (Unpublished): Durham University.

-

Kemp, A. (2000) ‘‘Border space and national identity in Israel.’’ In Y. Shenhav (ed.) Theory and Criticism: Space, Land, Home. Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: Van Leer Jerusalem Institute and Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House (Hebrew).

-

OHCHR – Office of the United Nations' High Commissioner for Human Rights. 1966. <http://www.ohchr.org/english/law/ccpr.htm>.>.

-

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics- PCBS (2009). .

-

Rowe C., Koetter F. (1978). “Collage City.” Cambridge, the MIT Press.

-

Roy, S. (1987) “The Gaza Strip: A Case of Economic De-development”. Journal of Palestine Studies, XVII, (1), pp 56-88.

-

Salmon C. (2002) “The Bulldozer War.” <http://www.counterpunch.org/salmon0520.html>

-

Venturi R. (1966). “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture.” New York, Museum of Modern Art.

-

Yiftachel O. (1996) “The Internal Frontier: the Territorial Control of Ethnic Minorities”. Regio Studies 30(5): 493–508.

-

Yiftachel O. 2005. “Neither Two States nor One: The Disengagement and “Creeping Apartheid” in Israel/Palestine”. The Arab World Geographer, Toronto, Canada.

::::::::::::::::__

[1][1] The land confiscated due to the Israeli Jerusalem Municipality’s decision of the expansion of the Jerusalem municipal boundaries, are parts of the British division of the middle and northern parts of Palestinian villages and cities, which is larger and therefore totally different than the existing administrative boundaries.

Prepared by:

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem