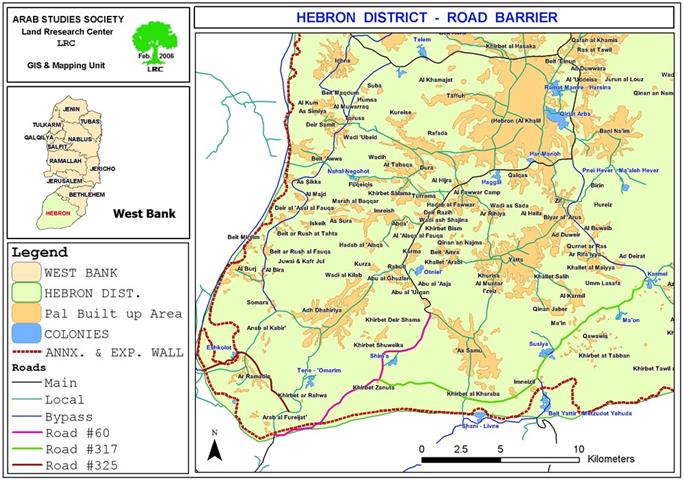

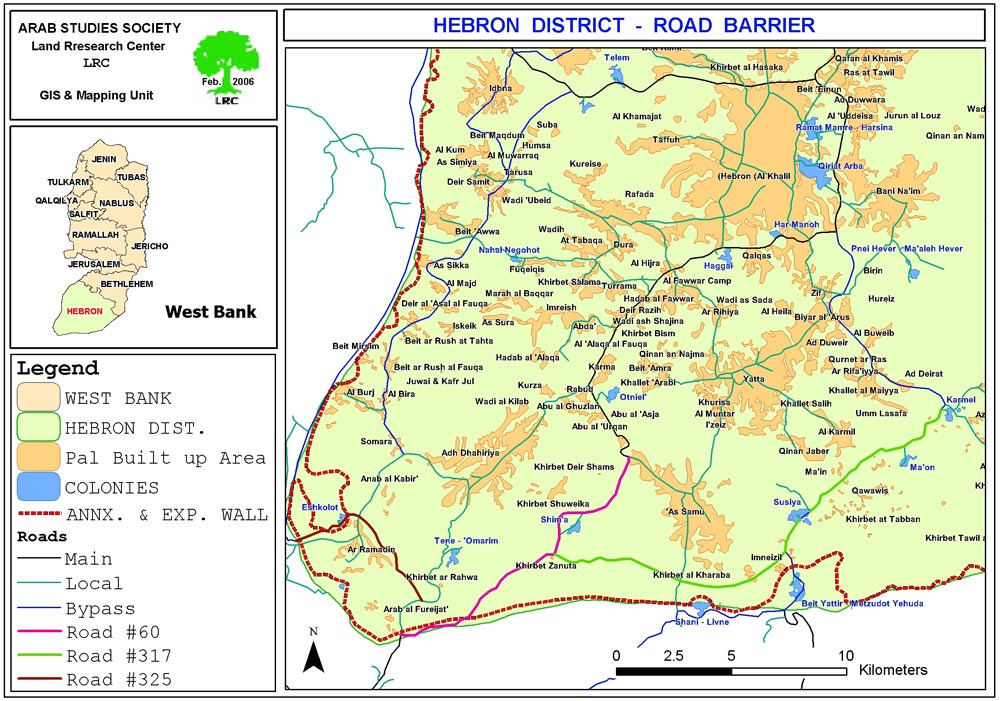

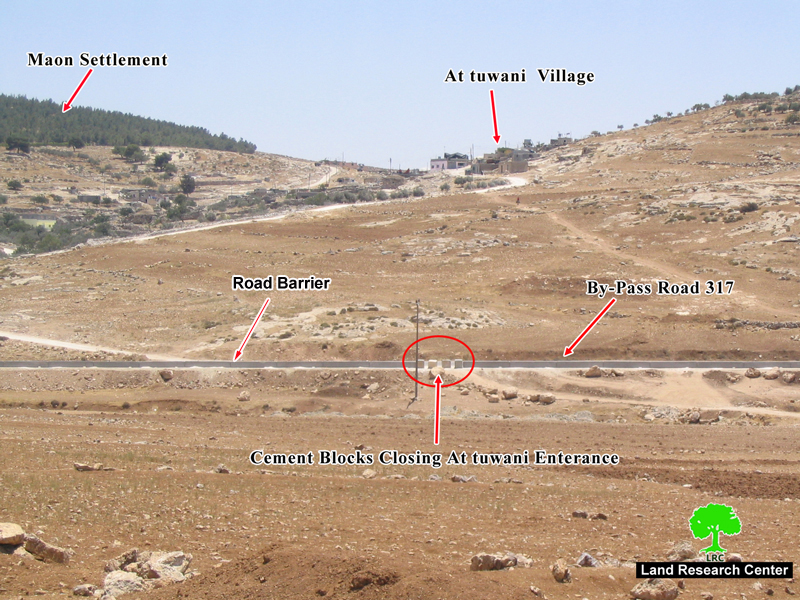

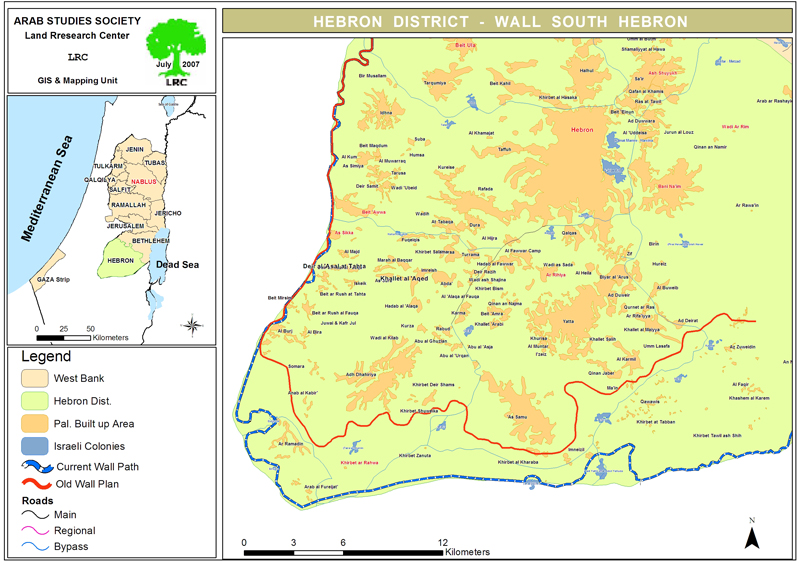

For the second time in 7 months, the Israeli supreme court issued a binding order asking the Israeli army to dismantle the road barrier that was set up along bypass roads number 60, 317 and 325 in southern Hebron in the year 2005. The barrier which was erected on security pretexts is about 41 km long by 82 cm high extending from the colony of Karmel in south east Hebron until the colony of Tene in south west Hebron, separating behind about 22 Palestinian communities in which more than 3000 live. The court took this decision in response to an appeal presented by the Israeli citizens rights movement on behalf of six Palestinian village and town councils in the affected area. The court, also, ordered the Israeli army to pay the amount of 30000 NIS as fees for the lawsuit. See Map 1

Last December, the Israeli supreme court issued its first decision on this issue giving the Israeli army a six month ultimatum to find suitable alternatives for the road barrier. But, the six months elapsed without the army proposing any alternatives for the barrier, which prompted the court's judge to rule that ' the army refused to dismantle the barrier or present any alternatives during the given period which is considered an act of carelessness, and, accordingly, I order the army to dismantle the barrier within 14 days'.

No security value

At a request by the supreme court, the Israeli council for peace and security presented a professional opinion about the security usefulness of the road barrier in which it confirmed that the barrier had no security value whatsoever. On the contrary, it increases the security risk on passengers traveling on these roads in south Hebron, according the verdict.

( Photo 1: the cement road barrier at the northen edge of bypass road No. 317)

Violation of supreme court's decision

In related event, the Israeli Ha'artz newspaper mentioned that an internal letter was prepared by the former Israeli defense minister, Haqai Allon – a copy of which was presented to the latest court's session – in which he confirmed that the security level violated the previous supreme court's decision. This act , according to the letter, is an insult to the court itself. The letter accuses the army of violating and belittling the court's decision for the purpose of achieving political gains which have nothing to do with security. He went on to say that it was obvious from the beginning that the road barrier had political objectives rather than security ones because it was built in areas that are in-crossable by vehicles, donkeys, cattle or even human beings.

In the Israeli doctrine, another Wall is possible ?!

In October, 2003, the Israeli army published plans for the route of the Segregation Wall in south Hebron which kept the belt of seven Israeli colonies on the southern side of the Wall, served by roads 60, 317 and 325, safely connecting them to Israel. The Wall would have trapped Palestinian communities living between it and the Green Line in an area of around 170,000 dunum, nearly 16 % of the land of the Governorate and the largest “seam zone” of the West Bank.

( Photo 2: the cement barrier flanking the northern edge of road No. 317)

This plan was ratified by the former Israeli premier Ariel Sharon. However, and due to the fear that the then proposed Wall path would not succeed in getting the supreme court's ratification, it was revised and put back near the green line. As an alternative, in December, 2005, the Israeli occupation army (IOA) released three military orders to requisite a corridor of land alongside roads 317, 60 and 325 which run from the colonies of Karmel to that of Tene in south Hebron. These military orders involved the construction of a continuous barrier of concrete running along the northern side of the three bypass roads and built within three to four meters of the edge of the road at the height of 82cm to prevent vehicles, donkeys and cattle from crossing onto the main road.

(Map 2: the old and current paths of the Segregation Wall in south Hebron)

The route of the 'road barrier' roughly follows the same direction of the 2003 plan for the Wall entrenching further the disconnection already evident on the ground and leading to complete isolation and the likelihood of displacement and loss of land.

Bypass Roads number 317 and 60 break up the transportation contiguity between Palestinian controlled areas in south Hebron ('area A', under Oslo II agreement), force Palestinians onto internal secondary roads, and fragment the territorial contiguity of the Governorate. The result is particularly dramatic in south Hebron where communities do not have the option of moving on internal secondary roads and have to cross bypass roads to access services and markets.

Israeli colonies in the area

The following is a list of Israeli colonies located on the aforementioned three roads (see map above) :

|

Colony name |

Date of establishment |

Population in 2005 |

Municipal area Dunum |

Built up area Dunum |

|

Karmel |

1981 |

330 |

1758 |

177 |

|

Ma'on |

1981 |

347 |

393 |

173 |

|

Susiya |

1983 |

700 |

1546 |

352 |

|

Mezadot Yehuda ( Beit Yattir) |

1980 |

431 |

2817 |

170 |

|

Shani |

1989 |

438 |

195 |

30 |

|

Shim'a |

1985 |

349 |

10597 |

212 |

|

Tene (Ma'ale Omarim) |

1983 |

532 |

8269 |

272 |

|

Eshkolot |

1982 |

225 |

6997 |

133 |

|

Total |

|

3033 |

21975 |

1307 |

Source: Foundation for Middle East Peace

Access and closure in south Hebron

Since October 2000, the IOA has progressively sealed off south Hebron, managing to disconnect resident Palestinians from urban areas further north through a combination of physical obstacles (road blocks, earth mounds and checkpoints) and the imposition of movement restrictions along roads 317 and 60 to Palestinian travel. Today, all exits to Palestinian villages along these two roads are blocked: no direct paved access is available to towns such as Ad Dhahiriya, Yatta and As Samu’.

Impact of the road barrier on Palestinians

According to LRC estimates, the 'road barrier' directly affects access to nearly 170000 dunum of agricultural land: 22 communities and over 3000 Palestinians are enclosed between the road barrier and the Wall which was built along the Green Line. The numbers grow during the spring and summer, when seasonal migration increases population figures by one third.

The livelihood of these communities is based on a combination of shepherdinginvolving the rearing of animals for sale as meat, and the sale of dairy products like cheese and yogurt. These products were traditionally transported and sold in Yatta and the Old Suq of Hebron. In addition, dry-land farming – entailing the rain-fed cultivation of grains, pulses, fodder and olives – and smaller scale cultivation of vegetables and tobacco for community consumption are central to livelihoods.

Access to land

Many of the shepherds living south of roads 317 and 60 own land on its northern sides and currently simply walk across them to reach grazing areas. The road Barrier causes in the best case a long detour for the shepherds who will have to find the nearest gate, hoping for it to be open. In the worst case represents an obstacle impossible for the animals to cross. It is estimated that there are about 24,730 heads of livestock in south Hebron, a percentage of needs to cross the road to access grazing areas on the other side. In addition, another 8,500 heads travel south every year during the seasonal migration to the area.

Palestinian owners of land who do not reside in the area stand out as another group potentially affected by the establishment of the “road barrier”. According to the records of the Land Registration Authority in the municipalities of Yatta, As Samu’ and Adh Dhahiriya, there are almost 3,500 families whose land holdings in the area are affected. However, as land registration was carried out by clan ('Hamula') under Jordanian rule, the numbers do not reflect current levels of ownership as plots of land have been divided among subsequent generations. The Municipality of Yatta recommends multiplying the overall figure by 20 to get a closer approximation to the current number of Palestinian owners.

Access to services

South Hebron has been largely overlooked and under-prioritized by the PNA Ministries providing basic services. Tasked with reaching more than half a million people in the Governorate, the local directorates of Health, Education and Social Affairs have struggled to extend the reach of the PNA to these area. The decentralization of institutions implemented to cope with the fragmentation of the West Bank that followed the imposition of closures was unsuccessful in south Hebron. More problematically, the designation of most of the land as “area C” under the Oslo Accords has prevented the PNA from developing any infrastructure at the local level to support these communities; the structures that have been built have all received demolition orders and some have already been demolished.

Currently, available basic services are minimal and most are out of the area, to be reached only by crossing roads 317 and 60. Secondary level education institutions are present in Al Karmil, Yatta, and As Samu’. The majority of teachers serving in the two schools south of road 317 (located in At Tuwani and Imneizel) are non-resident and are often prevented from reaching the institutions by IOA permanent and flying checkpoints along the bypass road. Already in 2004, the Directorate of Education in Hebron stated that the poor conditions in the area have resulted in lower attendance records and high drop out rates since the beginning of the intifada compared with the rest of the Governorate. See Photo 3

None of the existing health facilities are operational. The clinics in At Tuwani and Imneizel have received several demolition orders by the IOA Civil Administration. The Ministry of Health relies on international funding and NGOs to reach these communities with primary healthcare mobile clinics. Ambulances cannot reach patients in the south of Hebron without a detour of several kilometers. Families of patients prefer instead to reach the nearest earth mound or gate the emergency services can reach and transfer the patient across (back-to-back).

Access to markets

Residents of the communities south of 317 and 60 are dependent on the markets of Adh Dhahiriya, As Samu’, Al Karmil and Yatta. In the past, shepherds used to sell dairy and meat products to the Old Suq in Hebron, but the restrictions on movement and the difficulty in reaching the Governorate capital shifted the hub of trade and commerce to the south. Today, even reaching these local markets is problematic as crossing road 317 and 60 is not permitted by the IOF, especially after erecting the road barrier. To cope with this, merchants from the north have started to travel to these communities to overcome the unpredictable supply. Overall, however, the connection between the producers in rural areas and the sellers on the markets is deteriorating.

Markets to the north of road 317 provide many of the goods required by the communities in south Hebron, such as fodder for the animals, as well as water, clothes and food for their families. Traveling to the markets becomes crucial when fodder and water for the livestock run out; by the end of spring the land becomes arid again and there isn’t much grass to graze on for the animals while the rain-fed cisterns dry up by July. Clearly, with additional restrictions imposed on movement to the north, the ability to secure vital inputs and to derive an income to sustain their livelihood will reduce further.

Access to water

In addition to suffering from district-wide capacity and allocation constraints, the south of Hebron is poorly served by existing water networks. The Palestinian Water Authority plans to extend the regional network to the area south of As Samu’ and Yatta but the implementation is likely to take several years more. A large percentage of the rural communities rely on water trucking, particularly once summer begins and the rain-fed cisterns start emptying. As no filling points exist south of road 317 except further east, in the Bedouin communities of An Najada and Hameeda, water has to be brought in from Yatta where tankers are bought from either the Joint Services Committee or the Municipality.

(Photo 4:A water tanker trying to reach destination in south Hebron )

Social network

Almost all of those living in these communities are herders, traditionally sedentary and distinct from nearby Bedouin populations. Social connections and family ties with the urban areas of Yatta, As Samu’ and Adh Dhahiriya are very strong. Most of the communities in southern Hebron moved from those towns in the early decades of the 19th century when pressure on existing land reserves prompted outward migration toward the edges of the Hebron mountain range – an area that enjoys significant rainfall in winter.

The existing road barrier isolates them from their extended families, who would be discouraged from visiting the area. The separation would stifle the social linkages at the basis of these people’s 'fabric of life'.

Related case studies

1. Hebron's lands seized by road 'security' fences Hebron governorate, January, 2006.

2. Road barrier Replaces older Wall plan in south Hebron, February, 2006

3. The Segregation Wall in Hebron Governorate An update, June, 2006

Prepared by

The Land Research Center

LRC