The Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) is composed of two entities; the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Linking these has always been perceived as an inevitable necessity in building a viable Palestinian State. However, achieving this has always been impeded by the Israeli's under the pretext that a link would threaten its national security. To achieve a compromise between the two parties, the international community took the responsibility of formulating different proposals for the linking of the two entities as an indispensable character in building a viable Palestinian State in the foreseeable future.

Construction of a secure transportation link between Gaza Strip and the West Bank has been adopted by the international community as a flagship project during the last decade, mainly to prove that a viable two-state solution is feasible and enjoys a consensus vision. On the ground, the near total severance of links between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank makes such 'flagship projects' a matter of irony, where all the plans that have been brokered by the international community and state members of the Quartet are considered worthless as they are confronted by the Israeli apartheid policy and the de facto physical domination in and around the OPT.

The Israeli's find an independent and viable Palestinian State very hard to contemplate on the ground. On one hand, since the Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank including East Jerusalem back in 1967, Israel coerced to undermine any real action toward a comprehensive peace in the occupied territory by creating a de facto physical separation of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. On the other hand, what are referred to as the intellectual strip of the Israeli politics society re-proposed the status quo ante- 1967 where the Egyptians and the Jordanians had political control over the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, respectively.

Increasingly, the international community during the last couple of years has proposed several plans to link the Gaza Strip and the West Bank to insure the lawful right of the Palestinian people to live, work, and move freely in a contiguous geographic area and as well as to satisfy Israeli security interests.

While these plans are welcomed (they solidify the Palestinian stance of resistance toward the Israeli occupation in the OPT) they are not fully satisfactory and neglect in absolute terms the ABC's of logical regional planning, where the economic, social, environmental and cultural interests dominate political interests. However, in order to provide a context, the most recent international study plans will be introduced here. The first one entitled 'The Arc Plan: A Formal Structure for a Palestinian State and the other entitled 'AE Services for the Transportation Feasibility for Linking the West Bank & Gaza Strip.'

The Arc Plan: A Formal Structure for a Palestinian State:

An American corporation called RAND introduced after a two year study and US $2 million cost, a set of recommendations serving as a blueprint for a 'viable, independent and self-reliant Palestinian State' that includes development projects to improve the quality of life for Palestinians in the anticipated Palestinian State.

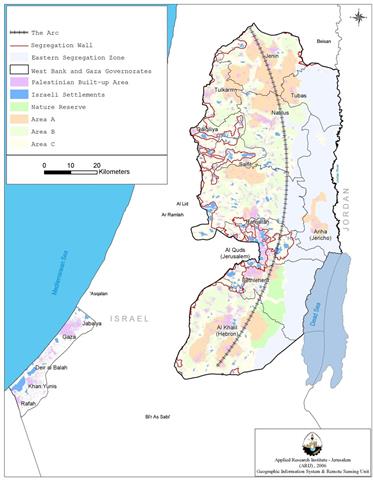

The study introduced 'The Arc Plan: A Formal Structure for a Palestinian State,' which is a high-speed train and fiber-optic network linking main Palestinian built-up areas in every Palestinian District in the West Bank to each other and with the Gaza Strip. The Arc Plan is a 140 mile corridor (225 km) which would include a rail line, highway, aqueduct and an energy network, of which 137 km of the railway crosses through the West Bank; half of this runs through areas A & B while the remaining half runs over area C.

In the broad sense, the plan is the first international practical initiative that supports the lawful right of the Palestinian people to live, work, and move freely in a contiguous geographic area (West Bank and Gaza). However, the plan does not address, in detail, issues of Israeli settlements, Jerusalem and state borders. As for Israeli settlements, the Arc ignores them as it penetrates major Israeli settlements like Ma'ale Adumim in Jerusalem and Itamar in Nablus. Such a proposal maybe interpreted by the Palestinians as a de facto recognition of these settlements and a consolidation for Palestinian subjugation to the Israelis, as illustrated in Sharon's 1991 'Seven Star Settlement Plan,' that outlawed the dismantling of major Israeli settlements including Ma'ale Adumim. (See Map 1: The Arc Plan) )

On the political level, the Palestinians feel that the Arc Plan will consequently redraw the West Bank eastern border with Jordan, as it runs in parallel with the Israeli Eastern Segregation Zone. Nevertheless, Palestinian environmentalists perceive the current path of the Arc Plan as ruinous to the Palestinian landscape and a waste of the Palestinian natural reserves along the eastern West Bank terrains.

In general, the plan neglects development of territorial lands on the western side of the West Bank and directs Palestinian development to the east; presumably to accommodate the return of refugees to new Palestinian cities away from the Green Line and consequently away from the western Segregation Wall, which constitutes the de facto border of Israel.

The plan, as it stands, limits the opportunities and alternatives of Palestinians who wish to commute from the north to the south, or vice versa, creating a land transport development dilemma. The plan suggests rebuilding the airport in Gaza to be the only air navigation facility for the OPT that allows Palestinians to travel abroad. Such a case would, at least, double the time and cost for travelers. According to the Plan, a Palestinian living in the north of the West Bank who wishes to access Jordan (the twin nation state for the Palestinians) must travel to the southernmost part of Gaza to get to Jordan; a journey that takes 90 minutes on the train plus 30 minutes on a plane compared to an estimated 20 minutes air trip from the center of the West Bank if using the closed Qalandyia airport.

Additionally, the plan still restricts the movement of Palestinians, especially between adjacent towns, where an individual is forced to head to the central business district to commute to the destination following specific time lines. See Map 1

AE Services for the Transportation Feasibility for Linking the West Bank & Gaza Strip:

A five months study that was undertaken at the bequest of USAID and supported by the World Bank was published in March 2006. The study was undertaken with the purpose of examining and determining the most economically rational options for transport linkages between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. The basic premise of this study supposes that economic prosperity is an interest shared by Palestinians and Israelis alike and that the free movement of goods and labor increases such prosperity. However, the study's symptomatic findings were guided and governed by political considerations according to the Israelis, whilst other considerations including eco- & socio-economics were either circumvented or given less weight. In fact, one may argue that the study ignored Palestinian interests as all considerations reflected Israeli realities on the ground. In short, the study's findings are virtually guided by an Israel political agenda rather than equitable interests of both parties.

The study was conducted using sound engineering practice and economic assessment in dealing with Israeli supremacy as regards restricted movement of Palestinian goods and labor as well as ongoing closure policy; measures that resulted in significant deterioration of economic conditions in the Gaza Strip and West Bank. This in turn threatens the stability of the Palestinian Authority and consequently the conflicted parties' ability to regenerate the peace process. It should be noted, that the proposed transport linkages in this study do not offer a panacea to end the deep distrust that now exists between Israelis and Palestinians.

The study considers 10 different transport alignments connecting the West Bank to the Gaza Strip along with a number of multiple combinations: road only, rail only, road and rail within the same corridor, and with different cross-sectional configurations; 'at grade' or ground level, sunken 'below grade' cross section for a road, and tunnel alternatives for rail.

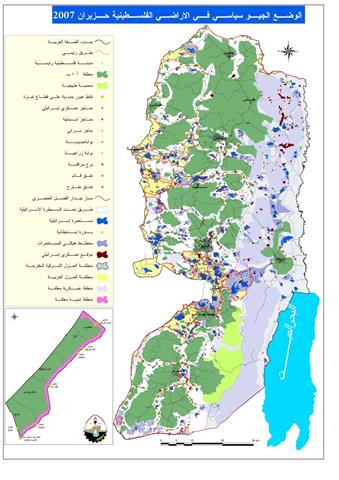

The analysis of these alignments is done in four stages on the basis of 1:50,000 scale mapping. Briefly, they are: (See Map 2)

-

Initial evaluation included ground level alternatives with two alternative end points on the West Bank – Tarqumiya almost directly east of the start point in the North West corner of the Gaza Strip and a second end point at a more southerly location in the West Bank. At this stages, the three southern alignments (Alignments 4, 5 and 6 and one northern alignment (Alignment 3) were dropped leaving Alignments 1 and 2.

-

Detailed evaluation of only Alignments 1 and 2 and their modal options.

-

Modification 1 to the contract requiring an investigation of a tunnel connection through Israel adding two new alignments to the study (Alignments 7 and 8).

-

Toward the end of the study, USAID requested an investigation of an interim solution that would entail using Israel Railways infrastructure between Gaza Strip to a turnout south of Kiryat Gat connecting to a tunnel for the remainder of the distance to the West Bank (Alignment 9). A further request made by USAID is a variation of this alternative substituting a ground level rail connection to the West Bank in lieu of a tunnel (Alignment 10). In both cases, the long-term solution would be an independent rail connection without the need to utilize Israel Railways' infrastructure. (AE Services for the Transportation Feasibility for Linking the West Bank & Gaza Strip, 2006).

Map 2: Proposed Transport Alignments to Link the Gaza Strip and West Bank

Before proposing the transport alignments or analyzing their ecological, economical and cultural aspects, it was very important to identify the locations of each of the proposed terminals in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. In the Gaza Strip the study suggested two terminals with an area not exceeding 0.6 km2 for each. The first one located at the northeastern part of the Gaza Strip (point A on map (2)), where the route continues eastward on the shortest route to the West Bank. The second terminal comes as an additional route; not as an alternative with the aim of providing a feasible congestion-free connection to the major traffic centers in Gaza Strip: i.e., Gaza City, Gaza Airport and/or the planned deep-water seaport (Point B on Map (2)). ).

On the West Bank side, the study proposed two terminals at Tarqumiya and Meitar, (points C and D, respectively, on Map (2)). Proposing the location of these two terminals was definable from an engineering point of view, where the topography of the West Bank was a major constraint, therefore, eliminating any alternatives to the earlier location(s, any other options will be considered unfeasible to implement. Proposing the location of these two terminals was definable from an engineering point of view, where the topography of the West Bank was a major constraint, therefore, eliminating any alternatives to the earlier location(s, any other options will be considered unfeasible to implement.

The exhaustive and time-consuming approach adhered to by planners, engineers and those involved in this study is noted, development of a dynamic traffic environment that necessitates links between Geographic Information Systems (GIS), state-of-the-art travel demand models, and traffic simulation software's is by far easily facilitated. However, the job of the developed dynamic environment could have been easier and more realistic if political constraints have been set aside. The majority of the proposed transport alignments followed tortuous paths to avoid passing Israeli settlements and cultivated areas, resulting in lengthy and expansive layouts according to individual proposals.

One may also criticize the logic adopted in proposing transport alignments. This took into consideration Israeli concerns with no regard to Palestinian welfare, while the average travel time between Gaza Strip and the West Bank is estimated at half an hour, an alternative route using railway will take at least one hour, keeping in mind that 'the shortest road alignment does not necessarily yield the most economical alternative'. Other than that, alternative traveling options restrict Palestinian traveling times to schedules suited to Israeli requirements subject to arbitrary security considerations. This will inflict economic burden on Palestinians. Such concerns and questions are legitimate for Palestinians to ask, especially considering that Israel's illegal 'bypass roads' in the OPT are constructed with no concern whatsoever to the Palestinian infrastructure, environment, or agricultural land loss.

The obvious question at this time would be; why spend such a hefty budget on studies to assess new alternatives to link the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, when the obvious and most feasible choice (regarding time as well as economic considerations) is at hand; the renovation and upgrading of the existing and proven best functional route.

To conclude, economic development and physical security are both indispensable if the peace process is to continue and progressively bring benefits that are ever more tangible to Israeli and Palestinian residents. Furthermore, agreements signed between the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and Israel resolved the issue of an established route between the Gaza Strip and West Bank. This did function for some time before Israel shunned its internationally recognized legal responsibilities under the pretext of security.

Prepared by

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem

ARIJ