The “High Court of Justice” has issued an evacuation order for one of the 28 houses to be evacuated and demolished in the Palestinian Al Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood in occupied East Jerusalem. As an occupied part of the West Bank, Israel has no right to issued and carryout such decisions, especially that East Jerusalem remains one of the main issues to negotiate between the Palestinian and the Israeli sides. The Israeli court decision is neither legally justified or morally. However, and in this respect is has been leading a methodological campaign against the Palestinians’ rights and very existence in the occupied city of East Jerusalem.

The storyline of Al Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood in occupied East Jerusalem started out back in the year 1985 when the contrive of the planned neighborhood illegally assumed control of a Palestinian expropriated property (the Shepherd Hotel) from the Israeli custodian of absentee property who has taken control of the hotel following the 1967 war, despite the fact the heirs of the rightful owner of the hotel (Grand Mufti Al-Haj Amin Al-Husseni) are still alive and long legal residents of Jerusalem. At the end of 2005, the planning committee at the Israeli municipality of Jerusalem authorized demolition of the Shepherd Hotel located in Karem Al-Mufti at the Palestinian Al Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood -but the order was not carried out to date-; in addition to that multiple city committee approvals were needed to add and to complete the application file number 11536 submitted to the Israeli Jerusalem municipality to build a complex project on 30 Dunums (including the land where the hotel is standing), which at the time of the application is to have 90 housing units, kindergarten and a synagogue.

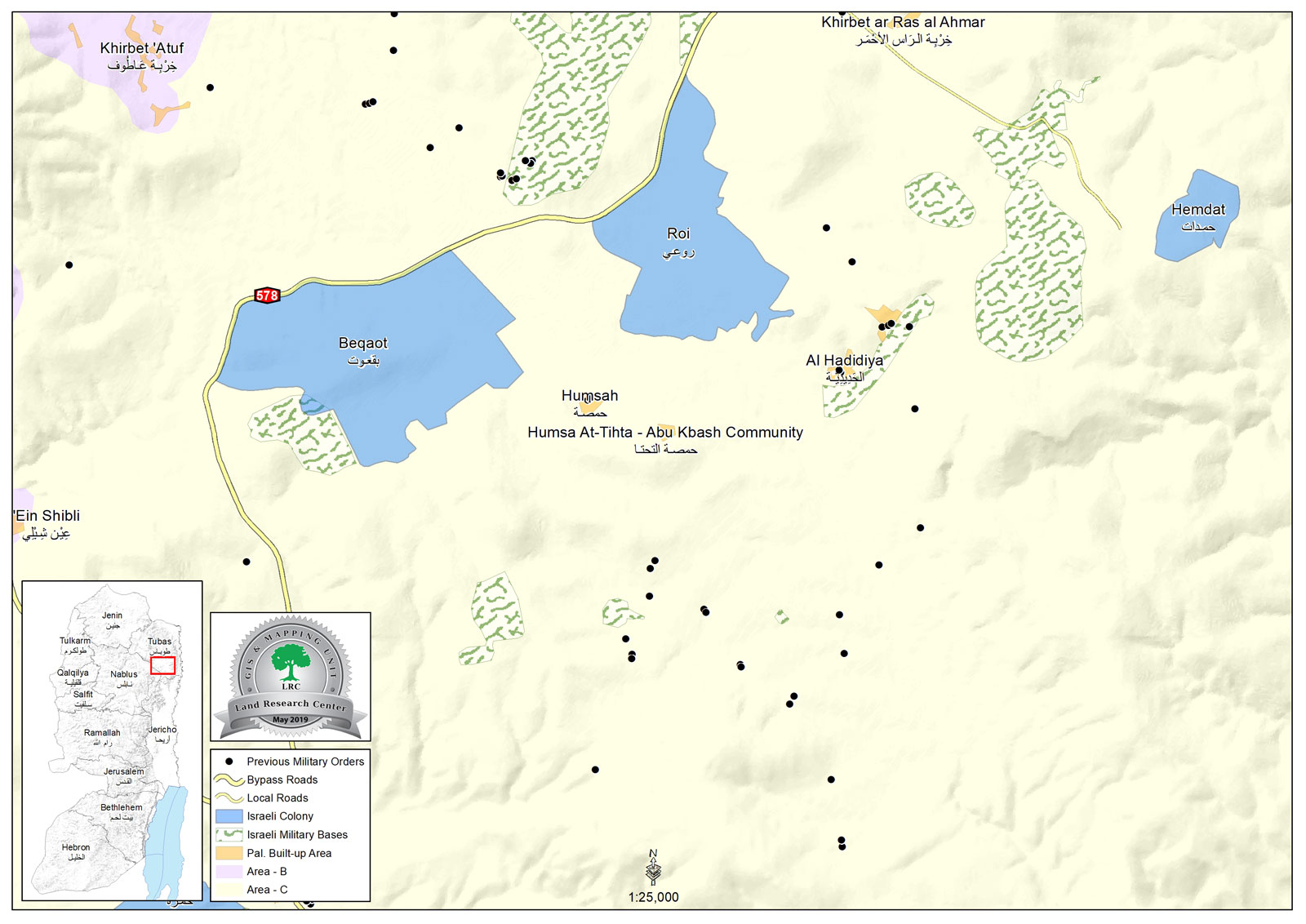

The plan for the new Israeli neighborhood will form the missing link between the illegal Jewish neighborhoods stretching from Mount Scopus (south of Shepherd hotel) where Shim'oun Hatzdik Tomb area became residence to some 8 Israeli families with an additional 4 dozen of yeshiva students and a cluster of various governments institutions including the national police headquarter to the north. See Map

The plan for the new illegal neighborhood goes much further than the immediate threat that hunts the shepherd hotel and its surrounding area to include an entire sector in the Al Sheikh Jarrah area called Karem Al-Mufti. In addition to the 30 Dunums that encompass the shepherd hotel and the lands surrounding it; an additional 110 Dunums (mostly cultivated with olive trees) of Karem Al-Mufti area falls under threat of being reclassified from an open and public space area to residential area once plans are developed to build a Jewish neighborhood.

Precedents to such activity took place in many areas, the most infamous of which are the Abu Ghanim Mountain and the Shu’fat hill cases; where the Israeli Jerusalem municipality reclassified the status of the mountain areas from “green areas” to residential areas; and are identified today by Israel as Har-Homa and Reches Shu’fat settlements.

An explicit violation to Oslo and the International Law

The plans for the new Israeli neighborhood, if implemented would compromise the terms of the Oslo Peace Accord which prohibit any of the conflicting parties to take any action that may alter the outcome of final status negotiation over Jerusalem.

The United Nations Security Council Resolutions 446 article 3 'Calls once more upon Israel, as the occupying Power, to abide scrupulously by the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention, to rescind its previous measures and to desist from taking any action which would result in changing the legal status and geographical nature and materially affecting the demographic composition of the Arab territories occupied since 1967, including Jerusalem, and, in particular, not to transfer parts of its own civilian population into the occupied Arab territories.'

The United Nation General Assembly resolution 2254 (ES-V) Reiterates its call to Israel in that resolution to rescind all measures already taken and to desist forthwith from taking any action which would alter the status of Jerusalem.

'Israel's country report under Article 9; submitted to the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination, CERD Committee, CERD/C/471/Add.2, 1 September 2005, Article 2, A.3. II. Judicial measures, paragraphs 38-47, p.10, 11'.

|

38. In H.C.J 6698/95 Ka’adan v. The Israel Lands Administration (ILA) (08.03.2000), The High Court of Justice held that the State of Israel was prohibited from allocating State land to the Jewish Agency for Israel for the purpose of establishing a community which would discriminate between Jews and non Jews. The petitioners, an Arab couple, wished to build a home in Katzir, a communal village in the Eron River region at the north of Israel. Katzir was established in 1982 by the Jewish Agency in collaboration with the Katzir Cooperative Society, on State land that was allocated to the Jewish Agency (via the Israel Lands Administration) for such a purpose.

39. The Katzir Cooperative Society only accepted Jewish members. As such, it refused to accept the petitioners and allow them to build their home in the communal village of Katzir. The petitioners claimed that the policy constituted discrimination on the basis of religion or nationality and that such discrimination with regard to State land is prohibited by law.

40. The court held in the Ka’adan case that the State may not allocate land directly to its citizens on the basis of religion or nationality. This conclusion is derived both from the values of Israel as a democratic State and from the values of Israel as a Jewish State. The Jewish character of the State does not permit Israel to discriminate between its citizens. In Israel, Jews and non Jews are citizens with equal rights and responsibilities. The court emphasized that the State will be viewed as engaging in impermissible discrimination even if it is also willing to allocate State land for the purpose of establishing an exclusively Arab town, as long as it permits a group of Jews, without distinguishing characteristics, to establish an exclusively Jewish town on State land. 41. Moreover, the Supreme Court held that the State may not allocate land to the Jewish Agency knowing that the Agency will only permit Jews to use the land, saying that where one may not discriminate directly, one may not discriminate indirectly. If the State, through its own actions, may not discriminate on the basis of religion or nationality, it may not facilitate such discrimination by a third party. It does not change matters that the third party is the Jewish Agency. Even if the Jewish Agency may distinguish between Jews and non Jews, it may not do so in the allocation of State land.

42. It should be noted that the Court limited its decision in the Ka’adan case to the specific facts of this case. The general issue of the use of State lands for the purposes of land development raises a wide range of questions, which are yet to be resolved. First, Ka’adan is not directed at past allocations of State land. Second, it focuses on the particular circumstances of the communal village of Katzir.

In discussing this issue, the Court did not take a position with regard to other types of settlements (such as the commune based Kibbutz or Moshav) or to the possibility that special circumstances, beyond the type of establishment, may be relevant, stating that:

'[I]t is important to understand and remember that today we are taking the first step in a sensitive and difficult journey. It is wise to proceed slowly, so that we do not stumble and fall, and instead we will proceed cautiously at every stage, according to the circumstances of each case.'

43. The Court rendered the decision that the State of Israel must consider the petitioners request to acquire land for themselves in the town of Katzir for the purpose of building their home. The State must make this consideration based on the principle of equality, and considering various relevant factors including those factors affecting the Jewish Agency and the current residents of Katzir. The State of Israel must also consider the numerous legal issues. Based on these considerations, the State must determine with deliberate speed whether to allow the petitioners to make a home within the communal town of Katzir.

44. As a response to the Ka'adan ruling, the Israel Land Administration, in cooperation with the Jewish Agency for Israel, issued new admission criteria to be applied uniformly to all applicants seeking to move into small, communal settlements established on State owned lands. These criteria stipulate that applicants must be over the age of 20, apply as an individual or a couple (including families), maintain sufficient economic resources, and maintain suitability to a small communal regime.

45. If the Committee rejects an application for admission, the reasons for rejection are to be based upon an objective, professional and independent opinion. Any criterion for admission to particular settlements is to be assessed in advance by the Administration and publicized. A decision by the Israel Land Administration also requires additional criteria to be included in the settlements Articles of Association. The inclusion of additional criteria in the Articles of Association requires approval by the Cooperative Associations Registrar. 46. The decisions of the aforementioned committees are subject to review by a Public Appeals Committee, to be chaired by a retired judge. Application forms and rules of procedure of the Appeals Committee are to be made available to the public.

47. A similar case still pending before the High Court of Justice is H.C.J 5601/00 Ibrahim Dwiri v. Israel Land Administration et al. The issue raised in this petition is the request of the Dwiri family to acquire a piece of land in the neighborhood of Kibbutz Hasollelim's expansion area, which was dismissed by the Kibbutz. Following the filing of the petition, the parties, the Dwiri family, the Kibbutz and the State, reached an agreement that the family would undergo the same selection/screening and acceptance procedures as any other entity interested in purchasing land in this neighborhood. In the framework of these procedures, the Kibbutz acceptance committee, on the basis of the opinion of the Institute of Evaluation which examined the family, concluded that the Dwiri family does not harmonize with the Kibbutz way of life. The family issued a counter opinion. |

Prepared by

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem

ARIJ