The aim of the report is to enlighten a wider audience about the reality of Israeli settlements inside the Palestinian Territory, although many political and security reasons exist to protect the facts around them, which has let the problem constantly grow up in the almost complete indifference of the international community.

|

‘Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, are illegal and an obstacle to peace and to economic and social development [… and] have been established in breach of international law’, commented the International Court of Justice on July 2004. Four years after, nothing really changed actually.

|

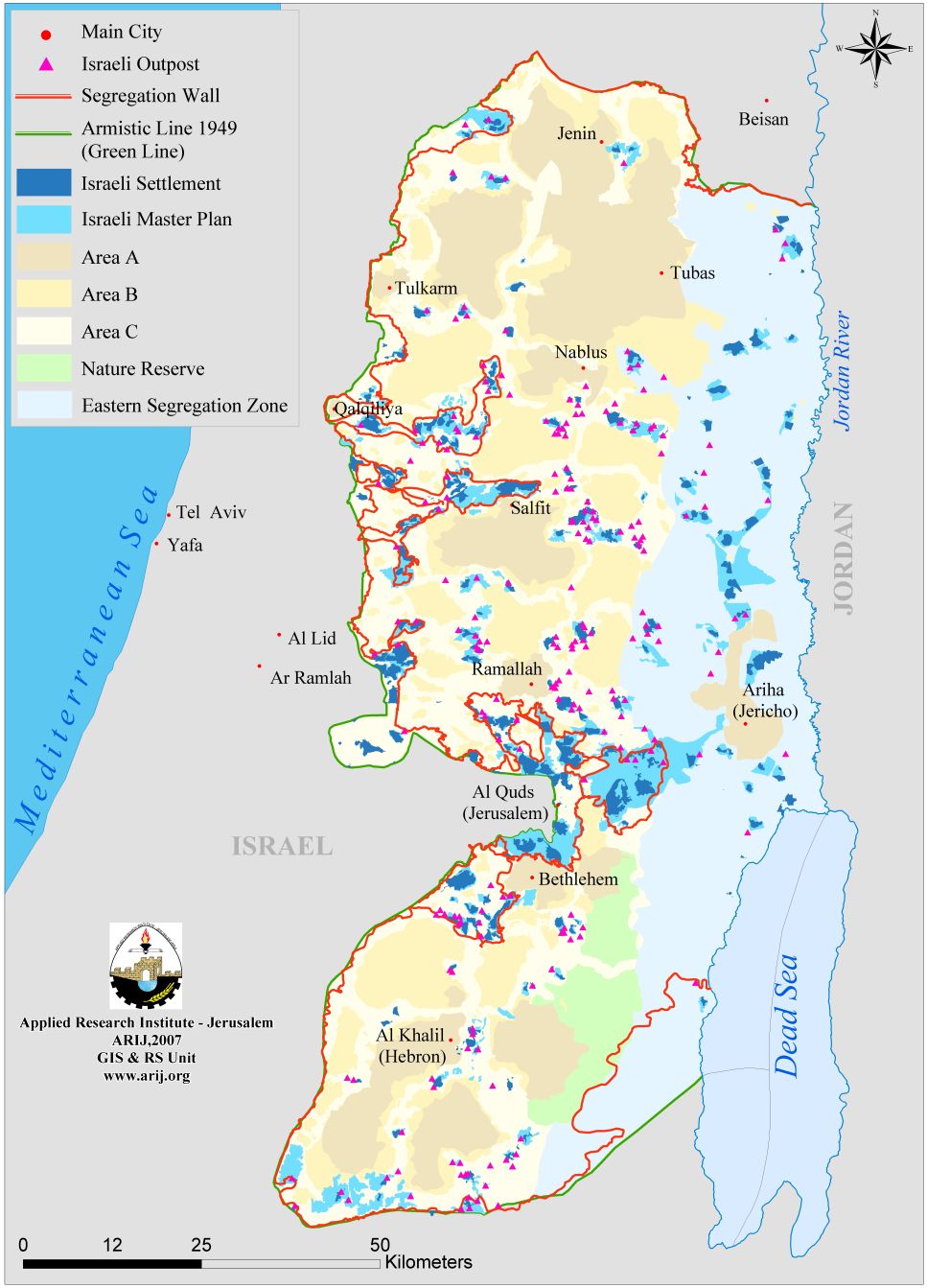

Israel has used a complex legal and bureaucratic mechanism to take control of more than 50 percent of the land in the West Bank. This land was used mainly to establish settlements and to create reserves of land for the future expansion of the settlements.

The principal tool used to take control of land was to declare it as ‘state land’. This process began in 1979 and is based on an engineered implementation of the Ottoman Lands Law of 1858, which applied in the area at the time of occupation. Other methods employed by Israel to take control of land include seizure for military needs, declaration of land as ‘abandoned assets,’ and the expropriation of land for public needs. Each of these is based on a different legal foundation. In addition, Israel has assisted private citizens purchasing land on the ‘free market’.

The process employed in taking control of land breaches the principles of the procedures and natural justice. It means that, in many cases, Palestinian residents were unaware that their land was registered in the name of the state, and by the time they discovered this fact, it was too late to appeal. The amount of proof always rests with the Palestinian claiming ownership of the land. Even if the Palestinian is able to establish meet such burden and establish ownership beyond doubt, the land may still be registered in the name of the state simply because it was transferred to the settlement ‘in good faith’.

Since the 1967 Arab – Israel War, successive Israeli governments have promoted and supported the settlement (colonization) in the West Bank and Gaza Strip by Israeli citizens. By 2003, there were in excess of 200,000 settlers residing in a number of villages and townships throughout those areas and at least the same number in the suburbs of east Jerusalem. Today, the number of Israeli settlers residing illegally in the occupied Palestinian Territory exceeds 550,000. The first phase in West Bank settlement activity took place under the Labor governments that remained in power until 1977. Known as the Allon Plan, after its initiator Deputy Prime Minister Yigal Allon, the settlement idea was a minimalist one, aimed at constructing a line of agricultural settlements along the new eastern border in the Jordan valley. This was part of a concept that assumed that civilian settlements contributed to the defensive posture of the country and that it was necessary to ensure defensible borders between Israel and Jordan.

The Allon Plan also proposed the establishment of additional settlements around Jerusalem and in close proximity to the Green Line border as a means of ensuring future territorial changes in favor of Israel. The rest of the West Bank region was deemed unsuitable for settlement because of the dense concentration of Palestinian population, unlike the Jordan valley, which was sparsely populated.

The Plan envisaged a situation in which the rest of the West Bank would eventually be part of an autonomous area under Jordanian administration and linked to the Kingdom of Jordan by means of a territorial corridor running from Ramallah via Jericho (the only major Palestinian population center in the Jordan Valley) to the border crossings on the Jordan River.

Following the Arab – Israel War of October 1973, a new religious nationalist movement, Gush Emunim (‘Bloc of the Faithful’), was established with the objective of promoting settlement throughout the West Bank and Gaza. They saw this as a means of extending Israeli control over the whole historic ‘Greater Israel’ (Eretz Yisraelha-Shelemah). They criticized the Allon plan for being minimalist and too compromising in its territorial claims. Those settlements were rejected by the Rabin government of the time, but later accepted in 1977 following the takeover of power from Israel’s first right-wing Likud government under the leadership of Menachem Begin.

Little by little, the Israeli governments have implemented a consistent and systematic policy intended to encourage Jewish citizens to migrate to the West Bank. One of the tools used to this end is to grant financial benefits and incentives to citizens – both directly and through the Jewish local authorities. The purpose of this support is to raise the standard of living of these citizens and to encourage migration to the West Bank. Actually the other reasons are to have more people supporting the ideology of a Zionist State and to easily raise the number of Israeli army attendants.

Most of the settlements in the West Bank are defined as national priority areas (A class or B class). Accordingly, the settlers and other Israeli citizens working or investing in the settlements are entitled to significant financial benefits. Six government ministries provide these benefits:

-

The Ministry of Construction and Housing (generous loans for the purchase of apartments, part of which is converted to a grant);

-

The Israel Lands Administration (significant price reductions in leasing land);

-

The Ministry of Education (incentives for teachers, exemption from tuition fees in kindergartens, and free transportation to school);

-

The Ministry of Industry and Trade (grants for investors, infrastructure for industrial zones, etc);

-

The Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (incentives for social workers);

-

The Ministry of Finance (reductions in income tax for individuals and companies);

In 2003, the Ministry of Finance cancelled the income tax reduction that residents of settlements previously received.

The Ministry of the Interior provides increased grants for the local authorities in the territories relative to those provided for communities within Israel. In the year 2000, the average per capita grant in the Jewish local councils in the West Bank was approximately 65 percent higher than the average per capita grant in local councils inside Israel. The discrepancy in the grants for the regional councils is even greater: the average per capita grant in 2000 in the regional councils in the West Bank was 165 percent of that for a resident of a regional council inside Israel.

One of the mechanisms used by the government to favor the Jewish local authorities in the West Bank, in comparison with local authorities inside Israel, is to channel funding through the Settlement Division of the World Zionist Organization. Although the entire budget of the Settlement Division comes from state funds, as a non-governmental body it is not subject to the rules applying to government ministries in Israel.

Settlement activity took off vigorously in the early 1980s when the planning regulations and restrictions were lifted to make it easier to create suburban communities as an alternative to agricultural and socially controlled small settlements. Under the slogan of ‘five minutes from

Kfar Saba,’,’

Israelis were now able to build detached houses on large land plots, which they received at a low cost and at the same time; retain their places of employment in the Tel Aviv and Jerusalem metropolitan centers. During the 1980s and 1990s, the road and transportation infrastructures linking Israel to the West Bank were developed, thus enhancing the appeal of the region for many Israelis who were attracted to settle there for economic rather than ideological or political reasons.

Following the first National Unity government of 1984, the Israeli cabinet announced

a freeze on all new settlement activity. Despite this and similar announcements by subsequent governments, settlement activity continued

at the same rhythm, even under the ‘pro-peace’ administrations of Yitzhak Rabin and Ehud Barak. At the most, there were periods in which no new settlements were formally constructed, but the expansion and consolidation of existing communities allowed for ‘natural growth’ never ceased. In fact, 13 settlements were established between 1993 and 1999. Under the Ariel Sharon administration after February 2001, militant settlers stepped up the constructed of new settlement outposts on their own initiative. These were deemed by the U.S Road Map Initiative of March 2003 for removal as they were described as impediments to the peace process.

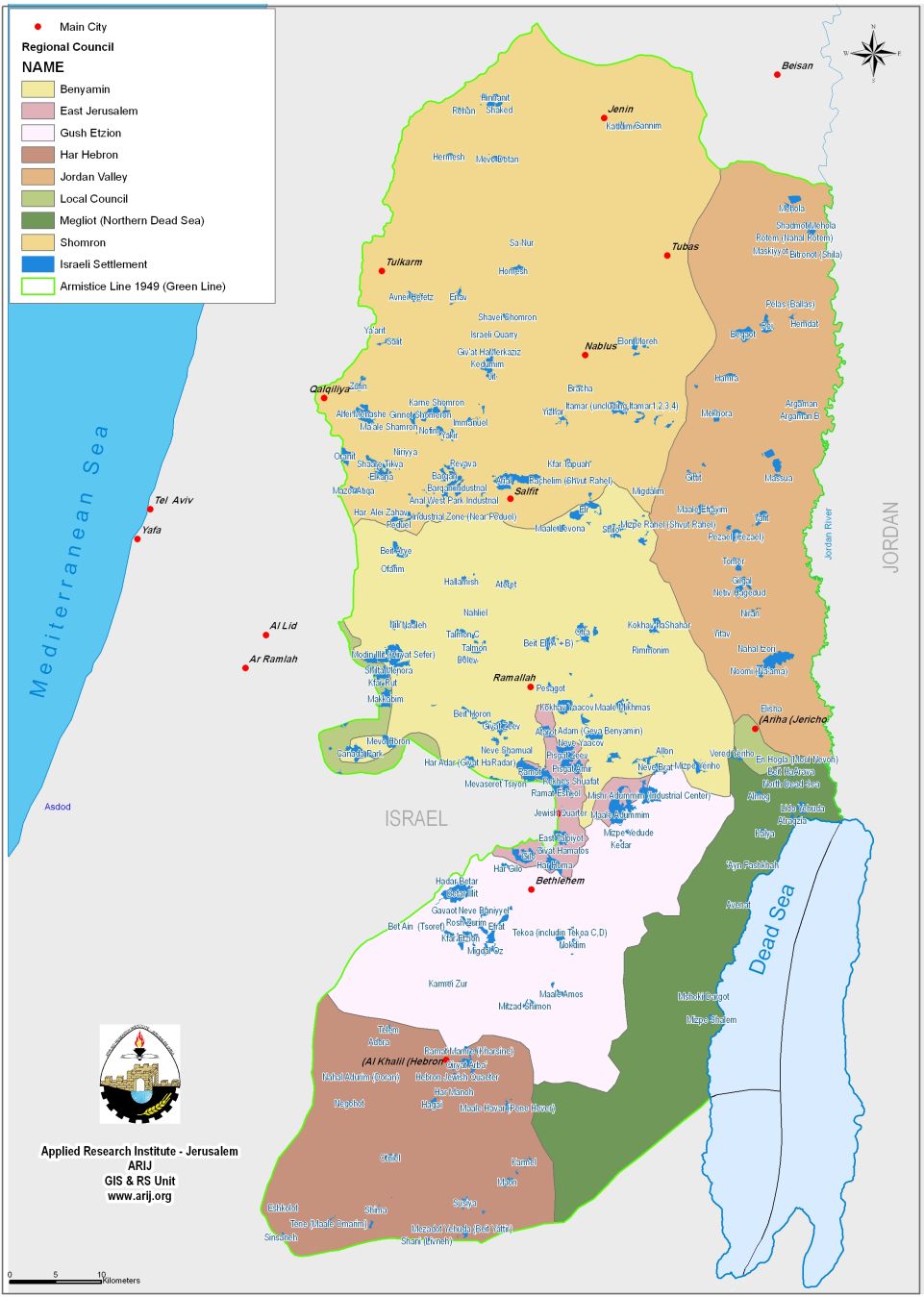

The settlements are organized in a system of small towns (some of them, such as Ariel, Emanuel, and Ma’ale Adumim, consist of over 20,000 inhabitants each) and villages. A system of municipal regional and local councils, similar to that in operation inside Israel itself, caters to their daily needs in the areas of public services, schools, health clinics, and welfare services. This system of local government operates totally independently and separately from the parallel, but much poorer, system that continued to function for the majority Palestinian population of the region.

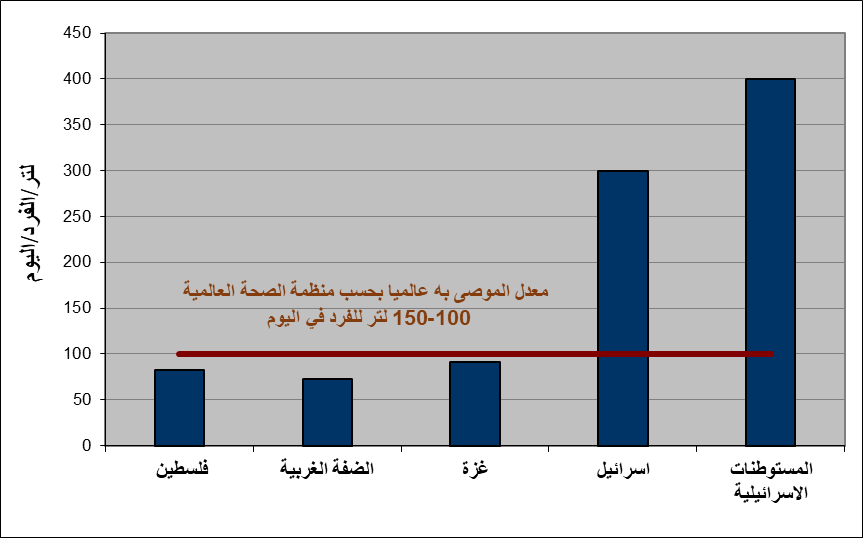

The establishment of the settlements has resulted in the expropriation of much Palestinian land in both the public and private domain. Israeli high court rulings at the end of the 1970s warned against the use of private land for such purposes, but there are differences of opinion concerning just what is private and what is public land. Under international law, even the use of public land in occupied territories can only be justified for defensive purposes in ‘good faith’, not for the sake of civilian settlement activity. Security problems during the Al-Aqsa intifada that broke out in September 2000 led Israel to destroy Palestinian olive groves, orchards, and other agricultural assets in attempts to enhance the safety of the settlers and their families. Similar concerns have also resulted in the construction of bypass and controlled-access roads throughout the region, enabling settlers to reach their homes without having to drive through the Palestinian towns and villages while causing disruptions to the normal movement of Palestinians.

Israel uses the seized lands to benefit the settlements while prohibiting the Palestinian public from using them in any way; and as the occupier in the Occupied Territory, Israel is not permitted to ignore the needs of an entire population and to use land intended for public needs solely to benefit the settlers.

The Israeli High Court of Justice has generally sanctioned the mechanism used to take control of land. In so doing, the Court has contributed to imbuing these procedures with a mask of legality. The Court initially accepted the state’s argument that the settlements met urgent military needs and allowed the state to seize private land for this purpose. When the state began to declare land ‘state land,’ the Court refused to intervene to prevent this process.

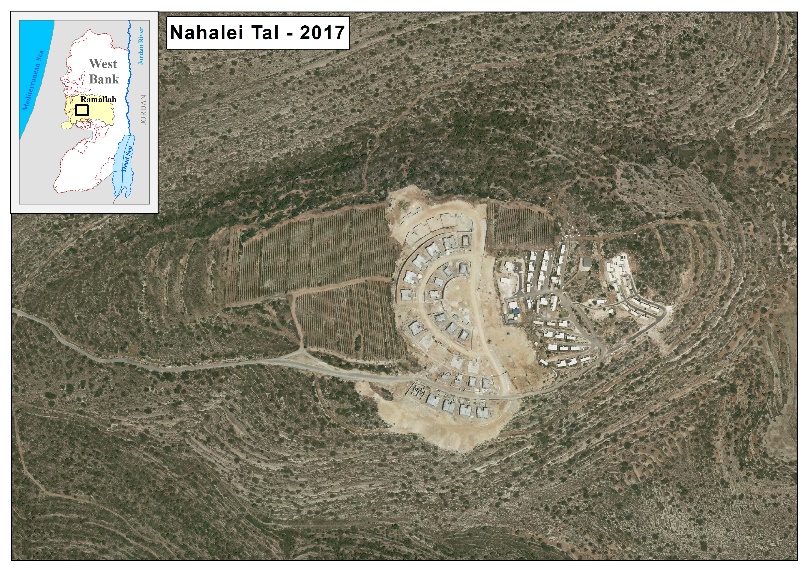

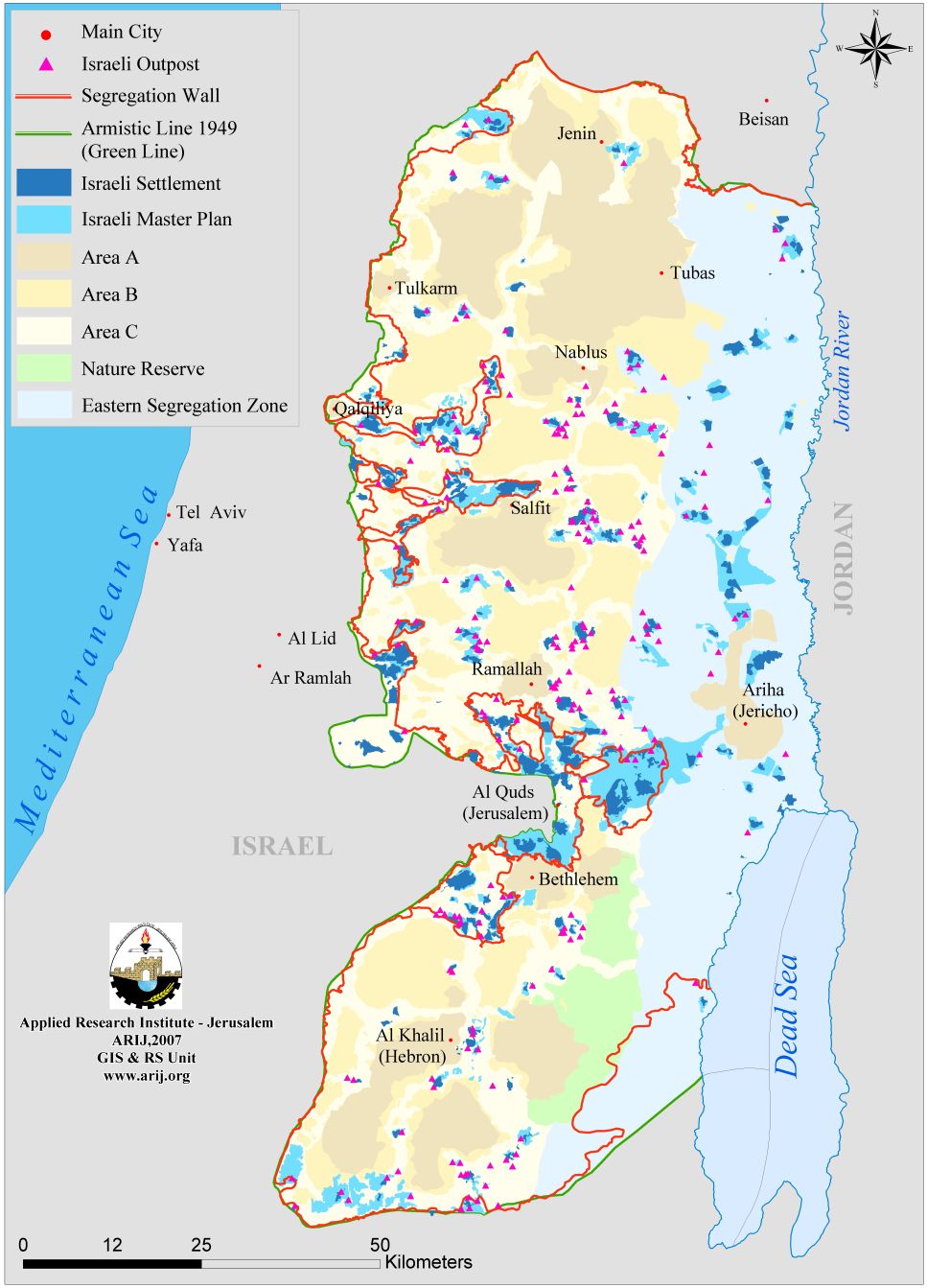

By the end of 2007, Israel established 199 settlements in the West Bank (not including the 16 settlements built in the Gaza Strip and four settlements north of the West Bank that were dismantled in 2005 during implementation of the ‘disengagement -redeployment- plan). The Israeli Ministry of Interior only recognizes 121 of them as “communities”, even though some of them contain stretches of land on which the built-up area is not contiguous. However, the 18 Israeli settlements located within the illegally defined boundary of the Israeli municipality of Jerusalem and annexed by Israel following the 1967 war are defined as neighborhoods of Jerusalem and not part of the communities’ lists. The number of settlers stood at 462,000. According to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, in September 2007, 271,400 settlers were living in the West Bank, excluding Jerusalem. In addition, based on growth statistics for the entire population of Jerusalem throughout 2007, the settler population in East Jerusalem is estimated at 191,000. The population of the settlements (not including East Jerusalem) grew faster than Israel’s general population: 4.5 percent compared to 1.5 percent. Some 40 percent of the settlements’ growth was comprised of Jews from Israel and abroad. However, population growth fell in comparison with 2006, when the settlements’ population grew by 5.8 percent. Moreover, there are additional 232 or so unrecognized settlements, referred to in the media as “outposts”, Israel recognize of which only 125 outpost. See Map 1

The Israeli administration has applied most aspects of Israeli law to the settlers and the settlements, thus effectively annexing them to the State of Israel. This has taken place despite the fact that, in formal terms, the West Bank is not part of the State of Israel, and the law in effect there is Jordanian law and military legislation. This annexation has resulted in a regime of legalized separation and discrimination. This regime is based on the existence of two separate legal systems in the same territory, with the rights of individuals being determined by their nationality.

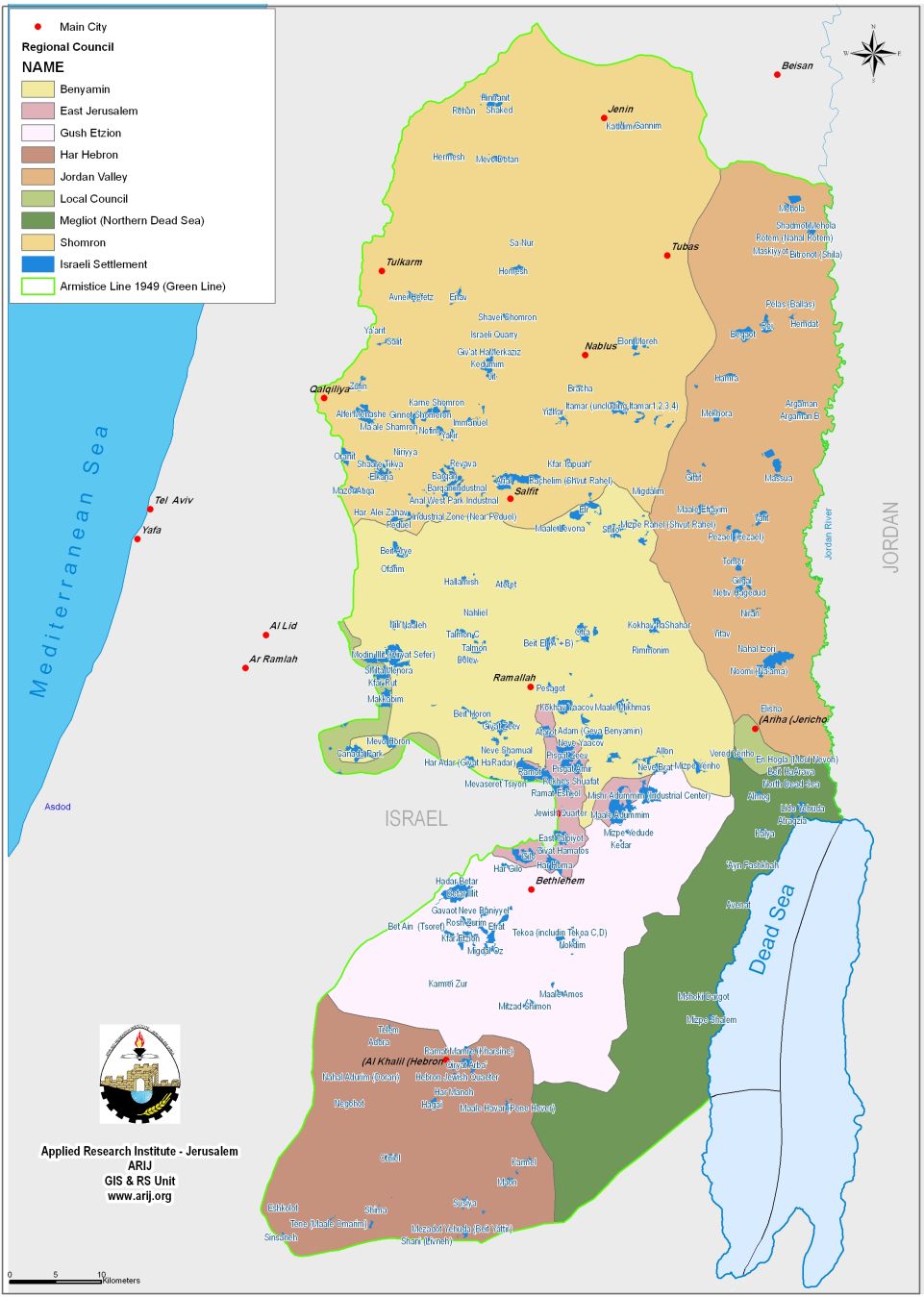

Local authorities for settlements were established similar to typical version inside Israel and are managed in a similar manner, ignoring the relevant Jordanian legislation that should apply in the West Bank. Twenty-three Jewish local authorities operate in the West Bank:

-

Four Municipalities (Ariel, Ma’ale Adumim, Betar Illit, and Modi’in Illit)

-

Thirteen Local Councils (Alfei Menashe, Beit Aryeh-Ofarim, Beit El, Efrat, Elkana, Giv’at Ze’ev, Har Adar, Immanuel, Karnei Shomron, Kedumim, Kiryat Arba, Ma’ale Efraim, Oranit)

-

Six Regional Councils, {Bikat HaYarden (Jordan Valley), Binyamin (Benjamin) Region, Gush Etzion (Etzion Bloc), Har Hevron (Hebron Mountain), Northern Dead Sea, Shomron (Samaria) Region}. See Map 2

In addition, eighteen settlements have been established in the areas annexed to the Municipality of Jerusalem in 1967 – areas in which Israeli law has been officially imposed.

The areas of jurisdiction of the Jewish local authorities, most of which extend far beyond the built-up area, are defined as ‘closed military zones’ in the military orders. Palestinians are forbidden to enter these areas without authorization from the Israeli military commander. Israeli citizens, Jews from throughout the world, and tourists are all permitted to enter these areas without the need for special permits.

The establishment of settlements in the West Bank violates international humanitarian law which establishes principles that apply during war and occupation. Moreover, the settlements lead to the infringement of international human rights law.

The Fourth Geneva Convention prohibits an occupying power from transferring citizens from its own territory to the occupied territory (Article 49). The Hague Regulations prohibit an occupying power from undertaking permanent changes in the occupied area unless these are due to military needs in the narrow sense of the term, or unless they are undertaken for the benefit of the local population.

The establishment of settlements results in the violation of the rights of Palestinians as enshrined in international human rights law. Among other violations, the settlements infringe the right to self-determination, equality, property, an adequate standard of living, and freedom of movement.

The issue of settlements has been a major point for discussion in all negotiations aimed at ending this conflict in the Middle East. Most observers agree that any future peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinians based on territorial compromise will necessitate the evacuation and removal of most, if not all, of these settlements. The inconclusive territorial negotiations that accompanied the Oslo Accords ignored the settlements issue altogether; since Israel had its own plan to redraw its eastern border in such a way as to include as many settlements on the Israeli side of the border – whether in exchange for territory elsewhere or as out-and-out annexation. The building of a unilaterally imposed Segregation Wall began in 2002 in effect implemented this policy on the ground.

Clearly, evacuation of the settlements will be complex and will take time; however, there are intermediate steps that can be taken immediately so as to reduce, to the extent possible, human rights violations and breaches of international law. For example, the government should cease new construction in the settlements – both the building of new settlements and the expansion of existing settlements. It must also freeze the planning and building of new bypass roads and must cease expropriating and seizing land intended for the bypass roads. The Israeli occupation government must surrender back to Palestinian villages all the non-built-up land that was placed within the municipal jurisdiction of the settlements and the regional councils, eliminate the planning boards in the settlements, and, as a result thereof, revoke the power of the local authorities to draw up outline plans and grant building permits. Also, the government must cease the granting of incentives to encourage Israeli citizens to move to settlements and must make resources available to encourage settlers to move inside Israel’s borders.

Prepared by:

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem

ARIJ