Road barrier replaces older Wall plan in south Hebron

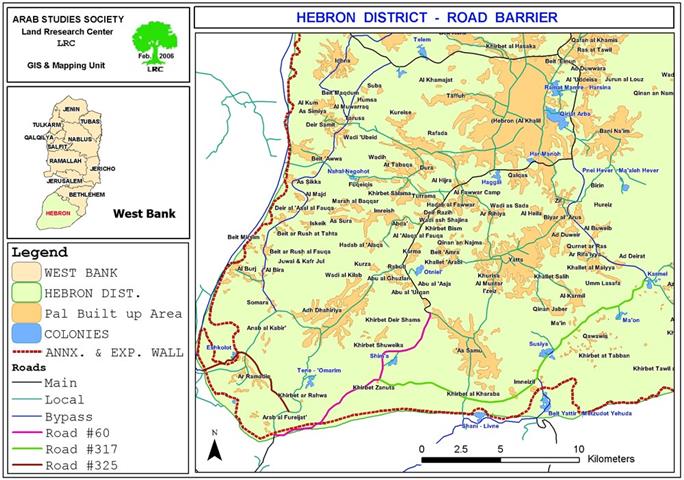

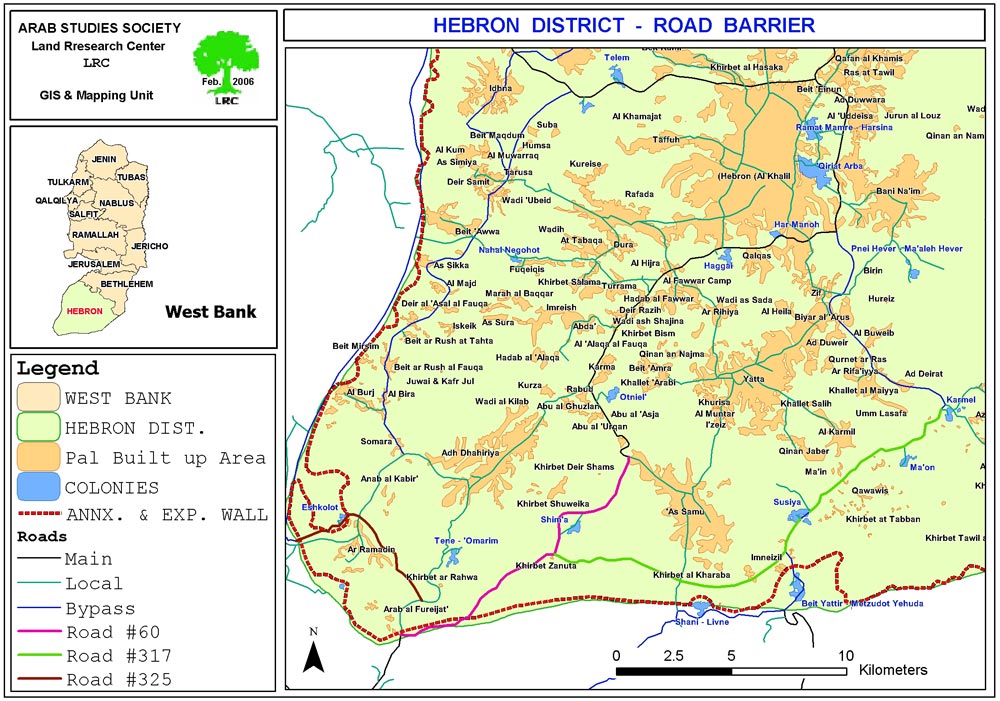

In December 2005, the Israeli occupation army (IOA) released three military orders to requisition a corridor of land alongside roads 317, 60 and 325 and which run from the settlements of Karmel to that of Tene in south Hebron.See Map 1

Map 1: roads # 60 and 317 south of Hebron

Map prepared by LRC. .

The IOA explained that the land would be used to erect a â??road barrierâ?? to secure the movement of Jewish settlers driving along the bypass roads by restricting Palestinian vehicular access onto them. The new security measure would directly benefit the nearly 3,800 settlers living in the belt of settlements and outposts connected by these roads and all those intending to reach southern Israel.

In January 2006, during a tour organized by IOA with representatives of affected Palestinian communities, IOA further explained that the new security measure would involve the construction of a continuous barrier of concrete running along the northern side of the bypass roads (317, 60 and 325). Built within three to four meters of the edge of the road, the barrier will be 80cm to 1m high to prevent vehicles from crossing onto the main road. Although not initially envisaged on the land requisition orders, it is understood that a series of gates would be established to enable Palestinians to move across the bypass roads and to the other side. The exact number and location of the gates has not been confirmed and the regime under which they will operate remains unclear.

Access and closure in south Hebron

Since October 2000, the IOA has progressively sealed off south Hebron, managing to disconnect resident Palestinians from urban areas further north through a combination of physical obstacles (road blocks, earth mounds and checkpoints) and the imposition of movement restrictions along roads 317 and 60 to Palestinian travel. Today, all exits to Palestinian villages along these two roads are blocked: no direct paved access is available to towns such as Ad Dhahiriya, Yatta and As Samu'. See Photo 1

Photo 1 : A water tanker descending an earth mound en route to

Khirbet Imneizel, Yata, south Hebron). Photo courtesy of LRC

These restrictions have been put in place to benefit and secure the movement of Jewish settlers residing in the Governorate, allowing them to move safely between settlements and further on to Israel without crossing a Palestinian. Roads 317 and 60 break up the transportation contiguity between Palestinian controlled areas ('area A', under Oslo), force Palestinians onto internal secondary roads) and fragment the territorial contiguity of the Governorate. The result is particularly dramatic in south Hebron where communities do not have the option of moving on internal secondary roads and have to cross bypass roads to access services and markets, breaching the security regime imposed by the IOA.

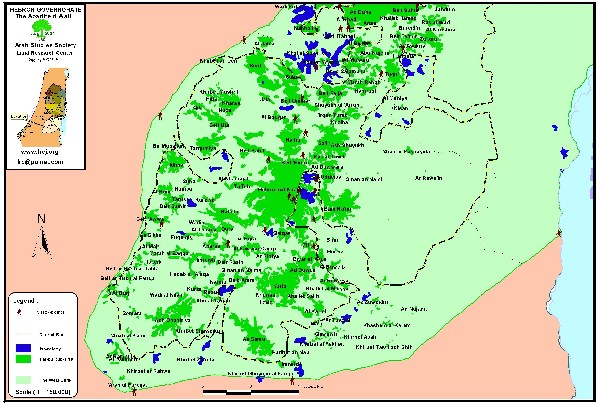

In 2003, the Israeli Ministry of Defense published plans for the route of the Annexation and Expansion Wall which kept the belt of Jewish settlements in the south Hebron on the southern side of the fence, served by roads 60 and 317, safely connecting them to Israel. The Wall would have trapped Palestinian communities living between it and the Green Line in an area of around 170,000 dunum, nearly 20% of the land of the Governorate and the largest 'seam zone' of the West Bank. A complex system of gates and permits to access land would have been established by the IOA to facilitate the movement for the resident population, possibly modeled along the system applied in the northern West Bank. See Map 2

Map 2: a re-production of the Israeli army's Wall map of Oct., 2003 annexing

the belt of Jewish settlements in the south of Hebron. Map prepared by LRC . Map prepared by

The route was eventually revised in February 20th, 2005 pushing the Wall to the Green Line, albeit with a couple of 'bubbles' where it veered back into the West Bank to incorporate the settlements of Metsadot Yehuda and Eshkolot.

The military orders issued by the IOA in December 2005 appear to be the result of a compromise solution to secure the protection of Jewish settlers along the bypass roads in south Hebron. The route of the 'road barrier' roughly follows the same direction of the 2003 plan for the Wall but it is also represents the last in the long list of closures cumulatively applied to roads 317, 60 and 325 to prevent access of Palestinians.

Although the details of the extent to which the IOA will facilitate the movement across the road for local Palestinian communities and owners of land are not available, the new security measure will entrench further the disconnection already evident on the ground, possibly leading to complete isolation and the likelihood of displacement and loss of land.

Impact of the road barrier on Palestinians

According to LRC estimates, the new â??road barrierâ?? will directly affect access to nearly 80,000 dunumof agricultural land: 22 communities and over 1,900 Palestinians will be enclosed between the road barrier and the Wall being constructed along the Green Line. The numbers grow during the spring and summer, when seasonal migration increases population figures by one third.

The livelihood of these communities is based on a combination of shepherdinginvolving the rearing of animals for sale as meat, and the sale of dairy products like cheese and yogurt. These products were traditionally transported and sold in Yatta and the Old Suq of Hebron. In addition, dry-land farming â?? entailing the rain-fed cultivation of grains, pulses, fodder and olives â?? and smaller scale cultivation of vegetables and tobacco for community consumption are central to livelihoods. See Photo 2

Photo 2:Palestinian farmers and cattle breeders grinding their seasonal

products near bypass road No. 317 south Hebron, , Photo courtesy of LRC

Photo courtesy of

Access to land

Many of the shepherds living south of roads 317 and 60 own land on its northern sides and currently simply walk across them to reach grazing areas. A road Barrier will cause in the best case a long detour for the shepherds who will have to find the nearest gate, hoping for it to be open. In the worst case it will represent an obstacle impossible for the animals to cross. It is estimated that there are about 24,730 heads of livestock in south Hebron, a percentage of which will need to cross the road to access grazing areas on the other side. In addition another 8,500 heads travel south every year during the seasonal migration to the area.. See Photo 3

Photo 3: A cattle herd in Khirbet Jinba that will be affected by the road

barrier south of Hebron, , Photo courtesy of LRC

Photo courtesy of

Palestinian owners of land who do not reside in the area stand out as another group potentially affected by the establishment of the â??road barrierâ??. According to the records of the Land Registration Authority in the municipalities of Yatta, As Samuâ?? and Adh Dhahiriya, there are almost 3,500 families whose land holdings in the area would be affected. However, as land registration was carried out by clan (â??Hamulaâ??) under Jordanian rule, the numbers do not reflect current levels of ownership as plots of land have been divided among subsequent generations. The Municipality of Yatta recommends multiplying the overall figure by 20 to get a closer approximation to the current number of Palestinian owners.

Access to services

Since the establishment of the Palestinian Authority, south Hebron has been largely overlooked and under-prioritized by the Ministries providing basic services. Tasked with reaching more than half a million people in the Governorate, the local directorates of Health, Education and Social Affairs have struggled to extend the reach of the PA to these area. The decentralization of institutions implemented to cope with the fragmentation of the West Bank that followed the imposition of closures was unsuccessful in south Hebron. More problematically, the designation of most of the land as â??area Câ?? under the Oslo Accords has prevented the PA from developing any infrastructure at the local level to support these communities; the structures that have been built have all received demolition ordersand some have already been demolished. See Photo 4

Photo 4: One of the toilets demolished in Khirbet At Tuwani

during 2004, Photo courtesy of LRC

Currently, available basic services are minimal and most are out of the area, to be reached only by crossing roads 317 and 60. Secondary level education institutions are present in Al Karmil, Yatta, and As Samuâ??. The majority of teachers serving in the two schools south of road 317 (located in At Tuwani and Imneizel) are non-resident and are often prevented from reaching the institutions by IOA permanent and flying checkpoints along the bypass road. Already in 2004, the Directorate of Education in Hebron stated that the poor conditions in the area have resulted in lower attendance records and high drop out rates since the beginning of the intifada compared with the rest of the Governorate.

None of the existing health facilities are operational. The clinics in At Tuwani and Imneizel have received several demolition orders by the IOA Civil Administration. The Ministry of Health relies on international funding and NGOs to reach these communities with primary healthcare mobile clinics. Ambulances cannot reach patients in the south of Hebron without a detour of several kilometres. Today an ambulance from Yatta can only reach At Tuwani in the south by traveling north first to the checkpoint of Dura/Fawwar. Families of patients prefer instead to reach the nearest earth mound or gate the emergency services can reach and transfer the patient across (back-to-back). See Photo 5

Photo 5: ruins of a demolished residential room in

Khirbet Mirkez, Photo courtesy of , Photo courtesy of LRC

Access to markets

Residents of the communities south of 317 and 60 are dependent on the markets of Adh Dhahiriya, As Samuâ??, Al Karmil and Yatta. In the past, shepherds used to sell dairy and meat products to the Old Suq in Hebron, but the restrictions on movement and the difficulty in reaching the Governorate capital shifted the hub of trade and commerce to the south. Today, even reaching these local markets is problematic as crossing road 317 and 60 is not permitted by the IOF, always busy reinforcing earthmounds along the bypass roads and constantly monitoring movement along them. To cope with this, merchants from the north have started to travel to these communities to overcome the unpredictable supply. Overall, however, the connection between the producers in rural areas and the sellers on the markets is deteriorating.

Markets to the north of road 317 provide many of the goods required by the communities in south Hebron, such as fodder for the animals, as well as water, clothes and food for their families. Traveling to the markets becomes crucial when fodder and water for the livestock run out; by the end of spring the land becomes arid again and there isnâ??t much grass to graze on for the animals while the rain-fed cisterns dry up by July. Clearly, with additional restrictions imposed on movement to the north, the ability to secure vital inputs and to derive an income to sustain their livelihood will reduce further.

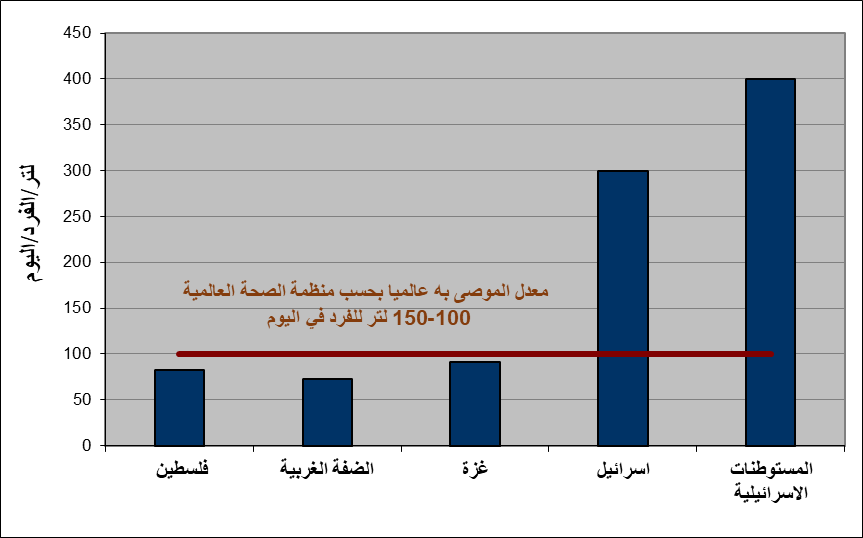

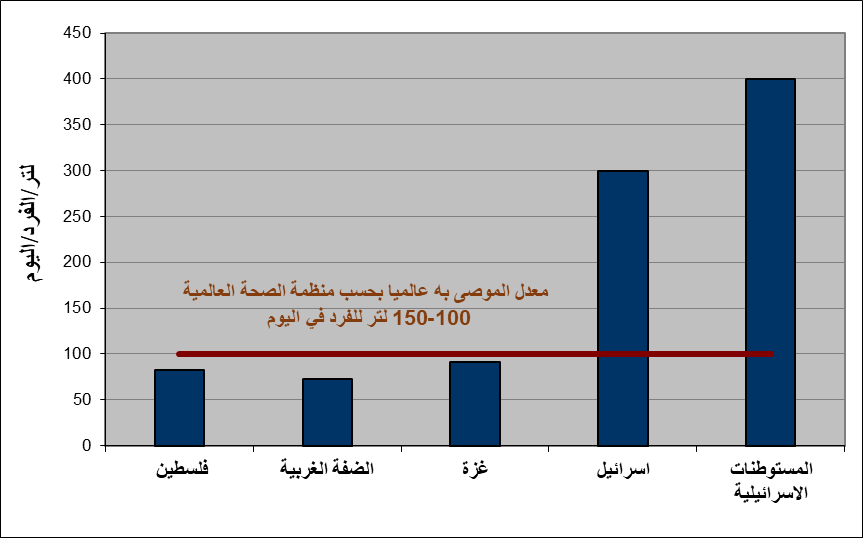

Access to water

In addition to suffering from district-wide capacity and allocation constraints, the south of Hebron is poorly served by existing water networks. The Palestinian Water Authority plans to extend the regional network to the area south of As Samu' and Yatta but the implementation is likely to take several years more. A large percentage of the rural communities rely on water trucking, particularly once summer begins and the rain-fed cisterns start emptying. As no filling points exist south of road 317 except further east, in the Bedouin communities of An Najada and Hameeda, water has to be brought in from Yatta where tankers are bought from either the Joint Services Committee or the Municipality. See Photo 6

Photo 6: A water tanker traveling through an olive orchard en

route to Khirbet At Tabban because of road closure, Photo courtesy of , Photo courtesy of LRC

Social networks

Almost all of those living in these communities are herders, traditionally sedentary and distinct from nearby Bedouin populations. Social connections and family ties with the urban areas of Yatta, As Samu̢?? and Adh Dhahiriya are very strong. Most of the communities in southern Hebron moved from those towns in the early decades of the 19th century when pressure on existing land reserves prompted outward migration toward the edges of the Hebron mountain range Рan area that enjoys significant rainfall in winter.

A road barrier would isolate them from their extended families, who would be discouraged from visiting the area. The separation would stifle the social linkages at the basis of these people's 'fabric of life'.

Khirbet Zanuta-distinguished suffering

In the western corner of the new seam zone area created by the road barrier lays the small Palestinian community of Khirbet Zanuta. Established almost 60 years ago, the community is composed of 11 families belonging to the extended families of Al-Tel, At-Batat and As Samareh all originally from the town of Adh Dhahiriya, further north. Khirbet Zanuta is divided in two sections by road 60 and three of the families live on the northern side.

The community of Khirbet Zanuta is highly dependent on links to services (schools and health clinic) and markets further north and any restriction on movement challenges the sustainability of the residentsâ?? livelihood. During the current intifada, the village has suffered from increasing geographical isolation and social disconnection: since October 2000, the IOF has blocked all of the roads connecting them to Adh Dhahiriya, and residents are weary of moving on roads 317 and 60 as they are almost exclusively utilized by Jewish settlers and the IOF.

For the leader of the community, the addition of a new 'road barrier' and a system of gates is likely to precipitate their isolation. It would separate the two sections of the village, and surely discourage visits by friends and relatives from Adh Dhahiriya. As a father of several daughters, he is particularly concerned over the implication the isolation of the village will have on the chances of securing marriage proposals for the unmarried women in the community. As a parent he is also sad to see his children stay away for long periods while at school in Adh Dhahiriya, a decision taken to avoid the long delays associated with the closures along the road. He worries that the distance will affect his relationship with his children and the bond within the family.

Although he is not sure what the 'road barrier' will bring in the future, he predicts for Khirbet Zanuta times of uncertainty ahead. The IOF has yet to inform the community of how they will move across road 60, and with over 3,000 heads of livestock in the village, and the need to cross the road to access grazing areas on both sides of it, he is not sure what the implications will be for the herders. The new obstacle could also deter merchants from coming to reach the village to buy cheese and livestock, a process the community has relied on during the intifada to cope with the difficulty to move with animals and access markets. The village makes approximately 60,000 JD from the sale of dairy products and another 180,000 JD from that of meat each year.

Table1. Palestinian communities south of 'road barrier'

|

|

Palestinian communities

|

Population statistics |

|

1 |

Saadet Thaâ??lah |

100* |

|

2 |

Khallet Athaba |

30 |

|

3 |

Isfey Foqa |

109 |

|

4 |

Isfey Tihta |

81 |

|

5 |

Maghayir al Abeed |

47 |

|

6 |

Tuba |

78 |

|

7 |

Al Fakheit |

68 |

|

8 |

At Tabban |

95 |

|

9 |

Al Majaz |

90 |

|

10 |

Halaweh |

52 |

|

11 |

Mirkez |

42 |

|

12 |

Jinba |

216 |

|

13 |

Mantiqat Shiâ??b al Batin |

144 |

|

14 |

Qawawis |

37 |

|

15 |

At Tuwani |

350 |

|

16 |

Imneizil |

193 |

|

17 |

Al Kharaba |

2 |

|

18 |

Haribat An Nabi |

50 |

|

19 |

Ghuwein Al Foqa |

44 |

|

20 |

Khirbet Zanuta |

50 |

|

21 |

Ratheem |

18 |

|

22 |

Wadi Al Khalil |

70 |

|

|

TOTAL |

1,896 |

*Source: Environmental Resources Management â?? estimate based on

project planning and implementation 2001-2004.

Table 2. Land ownership south of 'road barrier'

|

Municipality where land is registered |

Number of Palestinian owners** |

Amount of land owned (dunum)** |

|

Yatta |

1,537 |

63,780 |

|

As Samu' |

966 |

21,997 |

|

Adh Dhahiriya |

939 |

6,300* |

*Includes the area indicated in footnote 1.

**Source: Land Registration Authority (Yatta, As Samuâ?? and Adh Dhahiriya)

(Photo 7: A general view of Khirbet Jinba (the people of the caves) to be affected by the road))

Photo courtesy of LRC

::::::::::::::::__

[1] Order T/187/05, T/186/05 and T/185/0 were presented to the communities on 14 December 2005 to seize respectively 54, 40 and 138 dunum of land.

[2] The road barrier would benefit directly the settlements of Karmel, Maâ??on, Susiya, Metsadot Yehuda, Shani, Shima and Tene, as well as an additional 6 inhabited outposts.

[3] Roads 317 and 60 lead eventually to the Israeli city of Beâ??er Sheva and the Negev desert.

[4] The calculation includes also a 100m strip north of the bypass roads 60 and 317.

[5] This calculation includes land framed by roads 60, 325, and the settlements of Tene and Shima.

[6] The calculation includes also the 5,400 dunum of land that will be taken by the Wall when it veers into the West Bank to retain the settlement of Metsadot Yehuda.

[7] Seasonal migration to south Hebron typically occurs between March and September.

[8] The calculation is based on an assessment conducted by the Palestinian Hydrology Group in August 2005.

[9] This figure includes owners residing on the land south of road 317, who are registered in As Samuâ?? and Yatta.

[10] According to the Oslo Accords, the West Bank is divided into three areas. In â??area Câ?? the IOA keeps control over security but also administrative matters, such as building permits.

[11] This is the case for the school building in At Tuwani, for the additional classrooms built in Imneizel primary as well as for the health clinics of both villages.

Prepared by

The Land Research Center

LRC