Introduction

The Palestinian issue is central to the decades-old Arab – Israeli conflict. The Madrid conference offered a historic opportunity for arriving at a just and lasting peace in the Middle East, based on international legitimacy and the principle of land for peace. Yet, more than 9 years after Madrid, peace is still far away. Negotiations on the Israeli – Syrian and the Israeli – Lebanese tracks are frozen while the Israeli – Palestinian negotiations are stalled indefinitely. The Palestinian Authority accepted the Interim Agreement as a step towards a final peace treaty between Israelis and Palestinians. Its temporary interim nature needs to be respected by both parties. In particular, the agreement states that 'neither side shall initiate or take any step that will change the status of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip pending the outcome of the permanent status negotiations.' Yet, in reality Israel has and continues to violate and manipulate the Interim Agreement by creating de facto realities on the ground, which have severely fragmented the West Bank and Gaza Strip. This will not only affect the outcome of the final status negotiations, but also will render a future sustainable Palestinian entity unattainable and, more immediately, cause intolerable hardship and suffering.

The ongoing fragmentation of Palestinian land and communities into disconnected cantons combined with the frequent collective punishment of closures, house demolitions, withdrawal of identify cards, and the confiscation of private property will only impose a physically unsustainable and brittle peace. A lasting peace can only be based on United Nations Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338 as well as resolution 194 through which a fully sovereign Palestinian state will be established on the whole stretch of Palestinian land occupied by Israel in 1967 with East Jerusalem as its capital. In this respect, the international community is required to secure such an outcome and only then can the currently stalled peace process be set back on track.

Background

The twentieth century witnessed dramatic geopolitical changes, especially in the Middle East where state boundaries, which were carved essentially by superpowers, have remained a major source of conflict. The case of Palestine is a striking example. In 1923, the borders of mandate Palestine were defined to include an area of 27,000 sq. km. In 1948, a UN partition plan was proposed to divide Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. The Arabs rejected the partition plan on the ground that Jews, who owned less than 7% of the land at that time, could not be entitled to such a large proportion of historic Palestine. War erupted and the result was that by 1948 Israel had control over 78 % of mandate Palestine. In 1967, Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza. The West Bank, including East Jerusalem, covers an area of 5,854 sq. km, while Gaza strip covers an area of 365 sq. km.

The overall Palestinian population is estimated at 8.5 million, of whom 4.5 millions are living in their homeland while 4 millions are refugees who have been scattered and often live in harsh conditions in neighboring Arab countries and elsewhere. The right of refugees to return to their homes is internationally recognized by the world and is enshrined in the UN resolution 194. The refugees are waiting for a solution to their problem that has existed since 1948.

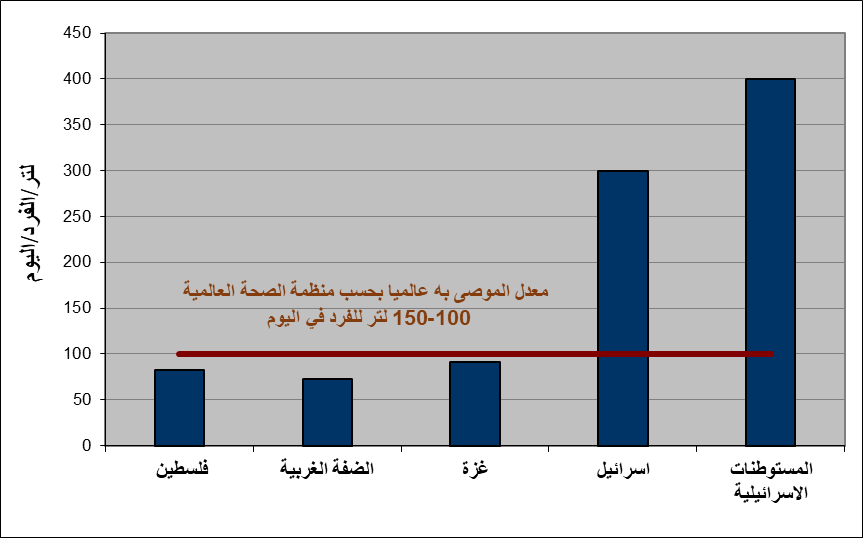

Soon after its occupation in 1967, Israel seized control over the West Bank and Gaza. Since that time, Israel has either confiscated or declared as closed vast areas of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, thereby placing them out of Palestinian reach. Palestinians are allowed to use less than 15% of their water resources. Israel has continued to expand Jewish colonies and their infrastructure on illegally confiscated Palestinian (mainly agricultural) land.

To reverse this unjust situation, the Palestinian people, by and large accepted the discourse of peaceful negotiations based on the grounds outlined in the Madrid Conference of 1991. The guiding principles of these negotiations were 'Land for Peace' and the United Nations' Resolutions 242 and 338. Likewise, the Oslo II Interim Agreement was accepted by the Palestinian Authority as an interim step towards a final peace treaty with Israel. It is interim in nature and should therefore be applied as such by the concerned parties. That is, ''neither side shall initiate or take any step that will change the status of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip pending the outcome of the permanent status negotiations.'' Yet, in reality, Israel has and continues to violate and manipulate the Interim Agreement by creating de facto realities on the ground that have severely fragmented the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a holy city for Muslims, Christians, and Jews where all believers should be guaranteed unrestricted freedom of worship. There is a need to maintain the unique identity of Jerusalem as a religious and cultural patrimony for all mankind. The international community has repeatedly declared that the Israeli actions and decisions in the parts of Jerusalem which were occupied in 1967 are, under international law, null and void.

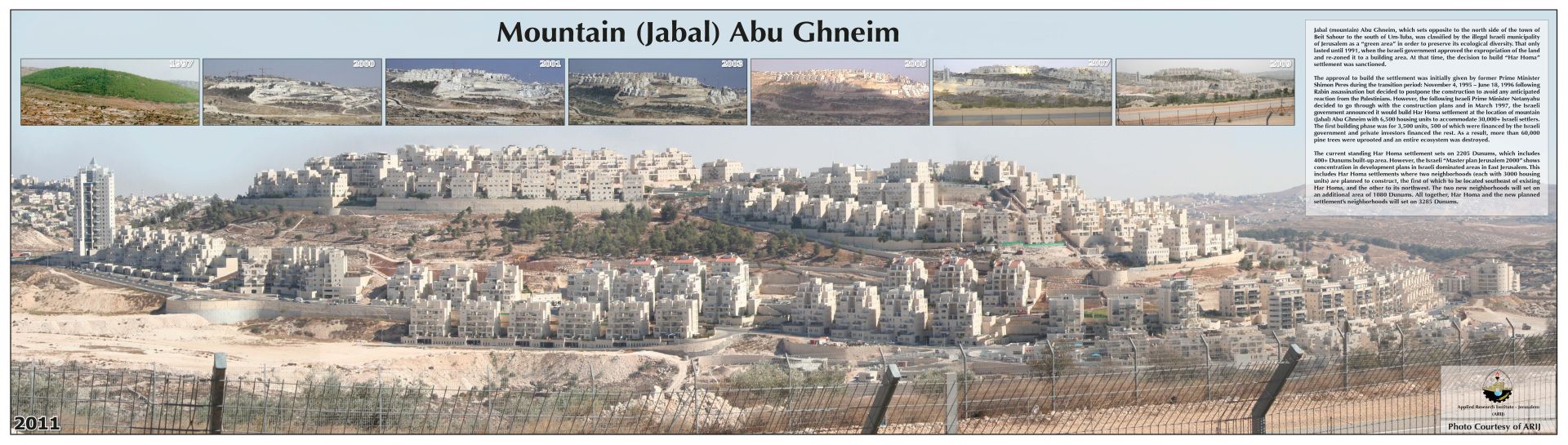

The issue of Jerusalem was postponed until the final status negotiations that have been stalled since their initiation in May 1996. However, in the meantime, the Israeli government has not stopped its unilateral practices in Jerusalem by which it creates de facto realities on the ground. These de facto realities are clearly affecting the outcome of the negotiations on the final status of Jerusalem to favor Israel, an action that is in total violation to United Nations' resolutions, particularly 298 and 242, as well as standing Palestinian-Israeli Oslo Agreements. Most recently, the Israeli Jerusalem Municipality approval of the new Jewish settlement of E-1 located adjacent to Ma'ale Adumim settlement, the initiation of a settlement in the Ras al-Amoud neighborhood of Jerusalem and the continued construction of Har Homa settlement on Jabal Abu Ghneim have all created more explosive realities on the ground.

Israel has staged measures leading to strong demographic shifts in order to create and maintain a Jewish majority in Jerusalem. De-development strategies have been adopted to restrict expansion of the city's Palestinian communities. In this process, infrastructure and services for this group of residents, by the Israeli Jerusalem Municipality, have become inadequate and do not provide a healthy living environment. Overcrowding has become the norm and the pressure on Jerusalem's land and natural resources has been devastating as well. Palestinian houses built without a license have been or are threatened to be demolished by the Israeli government. To further the Jerusalem Municipality's efforts to cleanse East Jerusalem of its Palestinian residents, a policy of canceling the Identity Cards of Palestinian Jerusalemites has been put into practice. This policy has led to the withdrawal of approximately 3,800 ID's between 1967-1996. In 1996 alone, 689 Palestinians from Jerusalem were deprived of their ID's. An additional 358 were confiscated in the early part of 1997. These figures do not include the approximately 10,000 Palestinian infants born in Jerusalem whom the Israeli Ministry of Interior has declined to register on their parents' identity cards.

The Geopolitical Background

Although the peace process has provided increased opportunities for Palestinian self-determination, the fact also remains that Palestine is not only underdeveloped but also still occupied. All land outside towns and villages, about 60 percent of the total land area in the West Bank, remains under Israeli control and more than 24 percent of the land in the Gaza Strip continues to be held by Israel. The 'Oslo II'' agreement, signed in Washington D.C. in September of 1995, sets out the interim stage for Palestinian Autonomy in the West Bank and Gaza, pending 'final status negotiations' that were scheduled to begin in May 1996 and finish by May 1999.

The Declaration of Principles (DOP), which was signed in 1993, called for an Interim period of 5 years during which the representatives of the Palestinian people and the Israeli government would initiate negotiations over the final status, which include Jerusalem, refugees, colonies, borders and water. It was also agreed upon that neither party should initiate any action during the interim period that might jeopardize the outcome of final status negotiations. According to the Oslo Interim Agreements, Palestinians gained control over 70 % of the Gaza strip and 3 % of the West Bank as area A and 24% as area B (see below for definitions). In January 1997, The Hebron protocol was signed in which 85 % of the city came under the PNA control (H1). 15 % of the city area was designated as area H2 and remained under Israeli control. H2 includes around 20,000 Palestinians and 400 Jewish settlers.

After a one and half year freeze, the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations were restarted and the Wye memorandum was signed in 1998, which included a detailed plan for implementation. Israel implemented the first phase and then new elections took place in Israel. At Sharm el Sheikh, a new memorandum was signed. The following table outlines the stages of the interim agreements.

Table 1: The Redeployment percentages according to the agreements

|

Agreement |

Date |

Area |

||

|

A |

B |

C |

||

|

Oslo II |

May 1994 |

3 % |

24 % |

73 % |

|

Wye I |

October 1998 |

10.1 % |

18.9 % |

71.0 % |

|

Wye II & III (not implemented) |

18.2 % |

21.8 % |

60.0 % |

|

|

Sharm I |

September 1999 |

10.1 % |

25.9 % |

64.0 % |

|

Sharm II (implemented in delay) |

January 2000 |

12.1 % |

26.9 % |

61.0 % |

|

Sharm III (implemented in delay) |

March 2000 |

18.2 % |

21.8 % |

60.0 % |

The Interim agreement divided the lands of Palestine into three classifications: areas A, B, and C. The Israeli military withdrew from lands classified as area A, and complete control was assumed by the Palestinian National Authority. This marked the first time that a Palestinian government retained sovereignty over any of their land. At present (March 2001), area A now comprises 1,004 sq. km of the West Bank and 254.2 sq. km of the Gaza Strip. In area B, the Palestinians have full control over civil society except that Israel continues to have overriding responsibility for security. These areas now constitute 1,204 sq. km of the West Bank. In area C, Israel retains full control over land, security, people and natural resources. This situation has remained static since the Sharm El Sheikh phase III redeployment in March 2000.

The status of Palestinian built-up areas lying in Area C after the March 2000 withdrawal is as follows:

1. There are 161 distinct ''islands'' of Palestinian control (i.e. Area A or Area B) surrounded by a sea of Area C.

2. There are 105 Palestinian villages that are still completely within area C and 216 that have parts in area C.

3. No Palestinian lives more than 6.5 km from a part of Area C

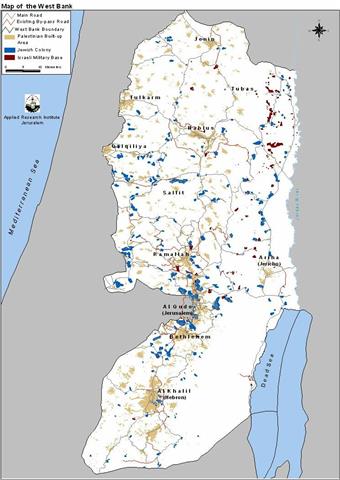

The jagged distribution of yellow and blue areas in the Gaza strip and areas A, B, C, H1 and H2 has partitioned the West Bank and Gaza into isolated cantons, which are physically separated from each other. For the current distribution of areas A, B and C in the West Bank see Map 1 and for the current status of the Gaza Strip see Map 2.

Map1: Geopolitical Map of the West Bank.

Map2: Geopolitical Map of the Gaza Strip.

According to Oslo II:

-

The Israelis should have withdrawn from all of the West Bank and Gaza Strip excluding the issues of the permanent status negotiations (i.e. Jerusalem and the colonies). It was agreed that 'West Bank and Gaza Strip territory, except for issues that will be negotiated in the permanent status negotiations, will come under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Council in a phased manner, to be completed within 18 months from the date of the inauguration of the Council..' Yet 60% of the West Bank remains under Israeli control

-

The two sides declared that they ''view the West Bank and the Gaza Strip as a single territorial unit, the integrity and status of which will be preserved during the interim period.'' Yet Israel has built colonies and bypass roads that hinder or totally prevent the connection between Palestinian localities.

-

No issues of the interim period should have been deferred to the final status negotiations (paragraph 6 of the preamble, Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and The Gaza Strip). The Sharm El-Sheikh Memorandum rescheduled the final redeployments of the interim period to be concurrent with the final status talks.

-

Normal and smooth movement of people, vehicles, and goods within the West Bank and between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip was supposed to be secured without obstacles. (Article I, Annex I, Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and The Gaza Strip). However checkpoints have become a daily feature in the life of ordinary Palestinians.

-

The Planning and Zoning of Area C were to be transferred to Palestinian jurisdiction ''except for issues that will be negotiated in the permanent status negotiation, during the further redeployment phases, to be completed with 18 months from the date of the inauguration of the Council.'' (Article 27, Appendix 1, Annex III: Protocol Concerning Civil Affairs, Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip). But in fact land confiscation, house demolition, and tree uprooting continue.

-

The release of prisoners was delayed so long that many ended up being released just a few weeks before the end of their prison sentence. In fact the Israelis even tried to bargain the release of some criminal convicts rather than political prisoners.

-

All the agreements reaffirm in one way or another that both sides should refrain from unilateral steps that prejudice the status of the West Bank and Gaza. Yet the growth of Jewish colonies has continued at an unprecedented pace.

Statistics show that Israeli encroachments on Palestinian rights rose significantly after the signing of the Oslo II agreement in September of 1995. Prior to the agreement, the violations were scattered and relatively low compared to those after it. See Figures 1 and 2. The graph shows a sharp rise in lands confiscated starting from the last quarter of 1996. It seems that after signing the agreements and examining the performance of the Palestinian Authority, the Israelis felt they had nothing to fear and that they could go about creating facts on the ground with impunity. Those who were misled to thinking that it was Netanyahu's government that was responsible for stalling the peace soon realized that the Barak government was no better. In fact, Israeli sources have confirmed that the Barak government has approved the construction of housing units at a quicker pace than that of his predecessor. This, if anything, shows that Israeli governments feel at ease in dictating their version of peace.

The logic of ''might makes right'' cannot make a just and lasting peace. If this peace is to be a comprehensive and sustainable peace, it must rise up to the Palestinian's legitimate claim of self-determination, national independence, and equitable distribution of economic dividends.

Disagreements over Withdrawal Percentages

In addition to the failure to and delays in implementing these agreements, there are further problems with the above stated percentages. For example, currently on the ground, area A comprises 1,004 sq. km of the West Bank. Area B now constitutes 1,204.4 sq. km of the West Bank. By dividing the area A over the overall area of the West Bank occupied in 1967, the actual percentage of Area A comes to 17.15 % of the West Bank area. However, according to the Sharm El-Sheikh Memo, the percentage of Area A should have been 18.2 %. By the same token, the actual percentage of Area B amounts to 20.57 % of the West Bank whereas according to the Sharm El-Sheikh Memo, the percentage of Area B should have been 21.8%.

This discrepancy comes from the fact that Israel omits certain parts of the West Bank when calculating the area of the West Bank. Those parts are:

Table 2: Parts of the West Bank that Israel omits.

|

Territory |

Area in sq. km |

|

No Man's Land |

50 |

|

Annexed East Jerusalem |

71 |

|

Territorial Waters of the Dead Sea |

195 |

|

Total |

316 |

Thus, quite to the convenience of the Israelis, the percentage of transfers appear larger than what they really are because they are calculated over a smaller patch of land. This is what happened when the Israelis claimed a 7 % withdrawal in Sharm El-Sheikh while actually it amounted to only 6.56 %.

Map 3: Location of West Bank areas omitted by Israel

Israel's hidden objective behind this discrepancy is to create the impression that the omitted areas are not part of the West Bank. That the No Man's Land, The territorial waters of the Dead Sea, and the annexed part of Jerusalem are beyond the scope of the legitimate rights of the Palestinians.

Israeli Settlements:-

Since the signing of the Declaration of Principles in 1993, Israel has followed a policy of creating de facto realities on the ground to affect the outcome of the final status negotiations. Israel has accelerated its colonizing activities by confiscating more Palestinian land to establish new colonies on hilltops and build a comprehensive network of by-pass roads. These activities have been a main source of the instability in the peace negotiations between the government of Israel and the Palestinians.

According to Israeli data there are 137 settlements in the West Bank and Gaza. However, satellite images show 282 Jewish built-up areas in the West Bank including East Jerusalem and 26 in Gaza. This is excluding military sites. These built-up areas cover 150.5 sq. km (GIS database, ARIJ, 2000). Israeli sources consider those Jewish built-up areas in East Jerusalem as neighborhoods of the municipal Jerusalem and not as settlements. Currently, the total number of settlers in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip number around 400,000 of which nearly 200,000 are in East Jerusalem alone.

Table 3: Land Use in the West Bank

|

Area in sq. km |

Percent of the West Bank |

|

|

Palestinian built-up areas in the West Bank |

367.7 |

6% |

|

Jewish colonies in the West Bank |

150.5 |

3% |

|

Israeli Military Base |

37.9 |

1% |

|

Closed Military Area |

999.1 |

18% |

Source: ARIJ database 2000

In the Gaza Strip, Israeli Settlements cover 53.8 sq. km. This area is occupied by only around 7,000 settlers.

Jewish colonies are scattered all over the West Bank while in the Gaza Strip they lie predominantly to the south along the coast. Successive Israeli governments have encouraged the development of specific blocks more than others. In the West Bank, the focus has been on the following areas:

-

the Jerusalem area to create demographic barricades in front of any Arab claims to it,

-

Along the West Bank's western edges so as to make the return to the 1967 borders practically impossible, and so as to make the colonies appealing to settlers commuting to work inside Israel.

-

The Jordan valley for its presumed importance to Israel's security as well as for its agricultural resources.

Furthermore, the growth of settlements is mainly geared to the formation of blocks; i.e. they grow outwards and towards each other. The end result of such a growth is the grouping of Palestinian towns and villages into three or four cantons. Indeed, the Israeli intention is to make the contiguity of any Palestinian State in the future practically unattainable.

The Labor and Likud Israeli governments have maintained progressive expansions of these colonies. To achieve this goal, they have confiscated Palestinian land, demolished their houses, and uprooted thousands of trees. Since the signing of the Declaration of Principles in 1993, more than 263,218 dunums of land have been confiscated, over 661 houses demolished and 96,894 trees have been uprooted in the West Bank alone. The reasons given for these activities include: building without a permit, the Absentee Law (which states that land not in use for three continuous years is subject to Israeli confiscation), and security purposes. At ARIJ, the change in the size of West Bank colonies is monitored by satellite. The results have been as follows. Table 4: The growth of Settlement Area in the West Bank

|

Year |

Settlement Area (sq. km) |

Percent of the West Bank |

|

1997 |

108.9 |

1.9 % |

|

1999 |

147.8 |

2.6 % |

|

2000 |

150.5 |

2.7 % |

Source: ARIJ database 2000

The following table details the expansions in the West Bank detected from the satellite images for August 1999 and October 2000.

Table 5: Details of Settlement Area Expansion in the West Bank

|

District |

|

Mother Settlement |

Expansion |

Area in Dunums |

|

Bethlehem |

1 |

Har Gilo |

New Expansion |

332 |

|

2 |

Neve Daniyyel |

New Expansion |

263 |

|

|

3 |

Kefar David |

Outpost_Sdeh Bar Farm |

125 |

|

|

4 |

Tekoa |

New Expansion |

122 |

|

|

5 |

Betar Illit |

New Expansion |

28 |

|

|

6 |

Alon Shevut |

Outpost_Givat Ha'hish |

19 |

|

|

7 |

Har Homa |

New Expansion |

18 |

|

|

Total |

907 |

|||

|

Hebron |

1 |

Migdal Oz |

New Expansion |

104 |

|

2 |

Ma'ale Amos |

Outpost_Ivei Ha'nachal |

87 |

|

|

3 |

Maon |

New Expansion |

33 |

|

|

4 |

Metzadot Yehuda |

Outpost_Nof Nesher |

31 |

|

|

5 |

Tene Omarim |

Outpost_Tene Omarim SE Caravans |

26 |

|

|

6 |

Suseya |

Outpost_Magen David Farm |

10 |

|

|

7 |

Tene Omarim |

Outpost_Tene Omarim N Caravans |

4 |

|

|

8 |

Maon |

Outpost_Maon Farm |

2 |

|

|

Total |

297 |

|||

|

Jericho |

1 |

near_Maale Efrayim |

New Site |

159 |

|

2 |

Pezael (Fezael) |

New Expansion |

22 |

|

|

Total |

181 |

|||

|

Jerusalem |

1 |

Pisgat Amir |

New Expansion |

77 |

|

2 |

Adam (Geva Benyamin) |

New Expansion |

62 |

|

|

3 |

2091950_near Ramot |

New Expansion |

38 |

|

|

4 |

Kokhav Yaacov |

New Expansion |

29 |

|

|

Total |

206 |

|||

|

Nablus |

1 |

Homesh |

New Expansion |

32 |

|

2 |

Bracha |

Outpost Beracha A |

16 |

|

|

3 |

2030350_Gvaot Olamn |

New Expansion Gvaot Olamn |

12 |

|

|

4 |

Mizpe Rahel ( Shvut Rahel ) |

Outpost Ahiya (Hill D) |

9 |

|

|

5 |

Shilo |

New Expansion |

8 |

|

|

6 |

Itamar |

Outpost Hil Neighborhood (Hill 777) |

8 |

|

|

7 |

Yitzhar |

Outpost Yitzhar Eastern Hill |

7 |

|

|

8 |

Yitzhar |

Outpost Ahuzat Shalhevet |

4 |

|

|

9 |

Bracha |

Outpost Sneh Ya'akov |

1 |

|

|

Total |

97 |

|||

|

Qalqiliya |

1 |

near Alfe Manashe |

New Site |

219 |

|

2 |

near Zufin |

New Site |

185 |

|

|

3 |

Neve Oranim |

New Expansion |

142 |

|

|

4 |

2050760 – near Alfe Manashe |

New Expansion |

9 |

|

|

5 |

Karne Shomron |

Outpost_Nof Kane Farm |

7 |

|

|

Total |

562 |

|||

|

Ramallah |

1 |

2081360 next to Shilo |

New Expansion |

156 |

|

2 |

Shilo |

Outpost Shillo East 2 |

48 |

|

|

3 |

Kochav Ha'shachar |

Outpost Mizpe Keramim |

35 |

|

|

4 |

Ofra |

Outpost Amona |

26 |

|

|

5 |

Shilo |

Outpost Givat Harel (Hill 740) |

17 |

|

|

6 |

Menora |

New Expanstion |

15 |

|

|

7 |

Shilo |

Outpost Shillo East 1 |

10 |

|

|

8 |

Halamish |

Outpost Zofit Farm |

7 |

|

|

9 |

Talmon North |

Outpost Haresha |

4 |

|

|

10 |

Shevut Rachel |

Outpost Adi Ad (Hill F, Hill 799) |

1 |

|

|

Total |

319 |

|||

|

Salfit |

1 |

Ginnot Shomeron |

New Expansion |

53 |

|

2 |

Yakir |

New Expansion |

39 |

|

|

3 |

Kefar Tapuah |

Outpost Kefar Tapuah Hill 660 |

35 |

|

|

4 |

Between Gavri'el , Barqan |

New Site |

7 |

|

|

Total |

134 |

|||

|

Tulkarm |

1 |

Avnei Hefetz |

Outpost Avnei Hefetz Eastern Caravans |

6 |

|

Total |

6 |

|||

|

Grand Total |

2709 |

|||

Source: ARIJ database 2000. (1 Dunum = 1000m2)

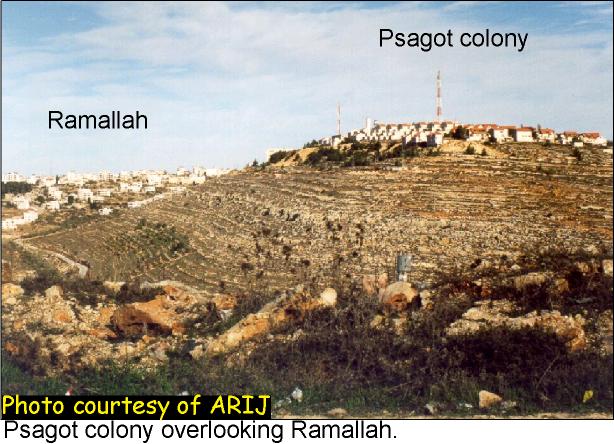

The colonies vary in size, function, and type. Some are big and have acquired city status (e.g. Arial, near the Palestinian town of Salfit) while others are small and amount to no less than a few caravans and a water tank (e.g. Magen David, south of the Palestinian village of Yatta). The Israeli settlements differ in their function too. The difference stems from the fact that colonizing activities in the West Bank and Gaza serve a prime Israeli political objective; dominating the demographic and economic aspects of Palestinian life. The great majority of settlements are situated in militarily strategic locations (e.g. Ariel has a strategic view over the Jordan Valley and the North); see photo. Some of the settlements overlook major Palestinian towns (e.g. Psagot over Ramallah); see photo. On the other hand, some act as wedges between Palestinian towns (e.g. the Gush Etzion block separating Bethlehem from Hebron). Settlemets are categorized mainly as urban, agricultural, industrial, and military. Thus, the type of structures and their numbers differ from one settlement to the other. The urban ones may have buildings with several stories while the agricultural have large tracts of cultivated land. They also have barracks and other structures that accompany agricultural activity. Hence the difference in type entails a difference in density and effect on the surrounding. The industrial type for example comprises a more serious threat to the Palestinian localities than the other types.

ALL Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza are illegal according to International Law. Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention specifically states that: ''The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.''

Figures released recently by the Israeli Housing and Construction Ministry show the public construction of 1,943 housing units in the occupied territories in the year 2000, while Labour Prime Minister Barak was in power. This is the highest number since the now Prime Minister Ariel Sharon (Likud) served as housing and construction minister in 1992 (Haaretz March 5th 2001).

By taking a look at the population growth in the last few years one observes the following:

Table 6: The Growth in Population

|

|

Israel |

|

Jews only |

|

Settlements in WBGS |

|

|

Year |

Population in thousands |

Growth |

Population in thousands |

Growth |

Population in thousands |

Growth |

|

1993 |

5327.6 |

4335.2 |

116 |

|||

|

1994 |

5471.5 |

3% |

4441.1 |

2% |

128 |

10% |

|

1995 |

5612.3 |

3% |

4522.3 |

2% |

133 |

4% |

|

1996 |

5757.9 |

3% |

4616.1 |

2% |

147 |

11% |

|

1997 |

5900.0 |

2% |

4701.6 |

2% |

160.2 |

9% |

|

1998 |

6041.4 |

2% |

4785.1 |

2% |

172.2 |

7% |

Source: Statistical Abstract of Israel, various issues.

The average growth rate for Jews in Israel is 2.0% per year (the rate including non-Jews is 2.5% per year). However, the population of the Jewish settlements grows at around 8.5% per year, which amounts to over four times the Israeli growth rate. Between 1996-98 there were 130 settlements that had an average annual growth of over 2%. That means that over 80% of the settlements grow at rates higher than the overall Israeli average.

Prime Minister Sharon's administration has declared that they will not shy away from building in settlements in order to accommodate their natural population growth. But the previous table shows clearly that the growth of the colonist population is far from natural. The tax breaks and cheap housing, coupled with the ideological drive means huge numbers of Israelis are moving into the occupied territories each year. It seems likely that this is the growth that the Sharon government will build to accommodate.

The ''Illegal'' Outposts

In a bid to show that its policy is different from that of the preceding government, Barak's government revised the status of 42 colonial outposts established after the signing of the Wye River Memo. The military establishment had advised Barak to dismantle 15 of the 42 outposts since they had legal problems:

-

8 outposts had proper permits,

-

27 had improper or incomplete permits,

-

7 had no permits at all.

Nevertheless, on October 13th a compromise was reached between the government and the Yesha council (speaking on behalf of the settlers) over the fate of those outposts. The number of outposts slated for removal were narrowed down to ten of which:

-

5 were empty or unmanned sites (i.e. containers or water tanks),

-

3 were relocated to nearby sites,

-

2 to be evacuated at a later time. Thus 32 outposts remained.

House Demolitions

The Israelis strictly monitor Palestinian land use within Area C. Building without a permit is forbidden, however, it is next to impossible for a Palestinian to obtain a building permit. Planted trees are consistently uprooted to discourage anything that could lead to an attachment to the land. Vast tracts of Palestinian agricultural land in this area continues to be confiscated by the Israelis under the pretext of the Absentee Law or security reasons.

The Israeli army repeatedly demolishes houses if they are built without a permit, or if they get in the way of Israeli construction plans (i.e., by-pass roads, settlements, military zones, etc.). At least 769 houses have been demolished since 1993 in the West Bank and Gaza (ARIJ database and Btselem records). The reasons given for these activities include: building without a permit, the Absentee Law (which states that land not in use for three continuous years is subject to Israeli confiscation), and security purposes. A small portion of these was demolished as punishment for Palestinians suspected or convicted of violence against Israel. Many of these charges have been challenged in a court of law, however, the Israeli court system very seldom rules in the favor of Palestinians. Through field studies, and using GPS positioning, ARIJ has mapped the location of Palestinian houses demolished, or slated for demolition, by the Israeli government. The locations of these acts of destruction repeatedly occur along both planned and existing by-pass roads, and at the outskirts of Palestinian communities. This serves to limit the growth and movement of Palestinians, and further the Israeli commitment to creating ''facts on the ground.''

produced after a survey in the south of the West Bank of 170 houses demolished or slated for demolition in 1998 (demolition order received by the household), clearly reveals the deliberate pattern behind the demolition of Palestinian homes in the West Bank. The homes indicated on the map in purple indicate three trends:

-

Nearly all homes slated for demolition are located in Area C, territory not yet handed over to the Palestinian Authority for governing control;

-

Nearly half (41% by ARIJ figures) are located along the perimeter of the West Bank, along the west and south borders as well as south of Jerusalem, between the Green Line and areas of Palestinian control;

-

Nearly all the homes are either along bypass roads or along the outskirts of Jewish settlements.

From these visual patterns indicated by the map, an analysis can be constructed of the rationale behind the demolition of homes. Demolition allows Israel to establish facts in Area C, to clear the area of Palestinian inhabitants and establish a claim to the territory in final status negotiations. Additionally, demolishing Palestinian homes effectively isolates Palestinian controlled areas, leaving Areas A and B as islands in a sea of Israeli control.

The map establishes that the construction of Israeli bypass roads is indeed a threat to Palestinians, whose homes are demolished in order to allow for a buffer zone around the roads. Additionally, the roads appear to establish a new Green Line border, farther within the West Bank, reinforced by the demolition of Palestinian homes along the west and south of the West Bank, and south and east of Jerusalem. Finally, the proximity of demolished homes to the perimeter of Jewish settlements indicates that the goal of settlement expansion is driving the Israeli government's demolition campaign. Not only does the expansion of these settlements threaten the homes of Palestinians living near the borders, it also creates a barrier to the expansion of Palestinian towns such as Bethlehem and Nablus.

To go to the Amnesty International comprehensive report on house demolitions Click here.

Bypass Roads

The term bypass roads came with the advent of the Oslo Accords and was not present before. Map 5 and Map 6 mark those roads built by the Israelis since the Oslo Accords. These roads are used by the Israelis to link settlements with each other and with Israel. In the agreements they are called 'Lateral Roads' but people usually call them 'bypass' roads because they are meant to circumvent (i.e. bypass) Palestinian built up areas. These roads are of course under Israeli control and entail a 50 to 75 meter buffer zone on each side of the road in which no construction is allowed.

Map 5: Map showing Bypass roads in the North.

Map 6: Map showing Bypass roads in the South.

The construction of by-pass roads commonly occurs along the perimeter of Palestinian built-up areas. As a result, these roads carve up the Palestinian areas into isolated ghettos and often deprive Palestinians of vital agricultural land. These practices have fragmented both land and people. This situation is very serious within the major cities of the West Bank where by-pass roads form asphalt boundaries that limit the expansion and development of the Palestinian communities, and further disconnect Palestinian communities from each other. Table 7: Bypass roads' length and buffer area in the West Bank.

|

|

Bypass roads |

||

|

Existing |

Under construction |

Total |

|

|

Total length |

316.7 km |

24.1 km |

340.8 km |

|

Area including 75m buffer zone |

47.5 sq. km |

3.6 sq. km |

51.1 sq. km |

Source: ARIJ database 1999

The results obtained for the changes in the by pass roads between August 1999 and October 2000 are shown below.

Table 8: The Changes in bypass roads between 1999 and 2000 in the West Bank

|

Bypass Road Location |

District |

Length in kilometers |

||

|

1 |

West of Negohot |

Hebron |

1.9 |

|

|

2 |

West of Adora |

Hebron |

4.7 |

|

|

3 |

Close to Shima |

Hebron |

3.2 |

|

|

4 |

South of Dolev |

Ramallah |

2.2 |

|

|

5 |

South of Shilo |

Nablus |

2.3 |

|

|

6 |

Between Barqan and Alei Zahav |

Nablus |

8.0 |

|

|

7 |

North of Maale Amos |

Hebron |

1.7 |

|

|

TOTAL |

|

24.1 |

||

Source: ARIJ database 2000

Closed Military Areas and Bases

Currently, 999.1 sq. km of the West Bank is declared as closed military area by the Israelis (17.6% of the total land area of the West Bank). However, this figure is the lowest since the occupation started in 1967. Before the Sharm El Sheikh Memorandum 1,214.7 sq. km was declared as closed military areas. In addition, military bases in the West Bank cover a total area of 37.9 sq. km. In the Gaza Strip, 2.27 sq. km is taken up by a military base and a further 53.69 sq. km is occupied by the Israeli security zone.

The Current Situation

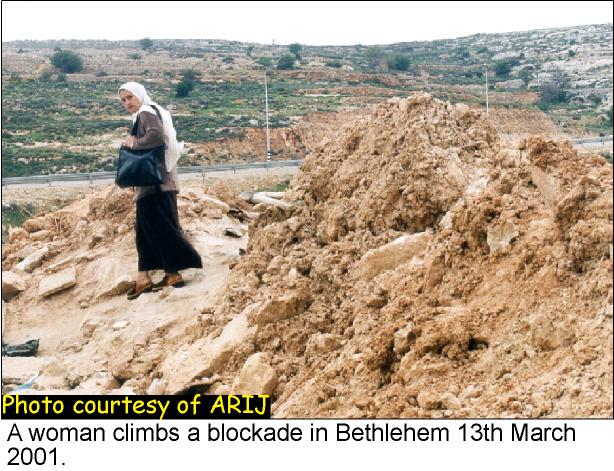

The Al Aqsa Intifada has made strikingly clear how damaging this current set up is for the ability of the Palestinian people to manage their own affairs, and to govern effectively. Since the beginning of October, the Israeli government has broken up the West Bank and Gaza into tens of cantons by physically blocking roads that link area A with area B with huge mounds of dirt and concrete blocks; see photo.

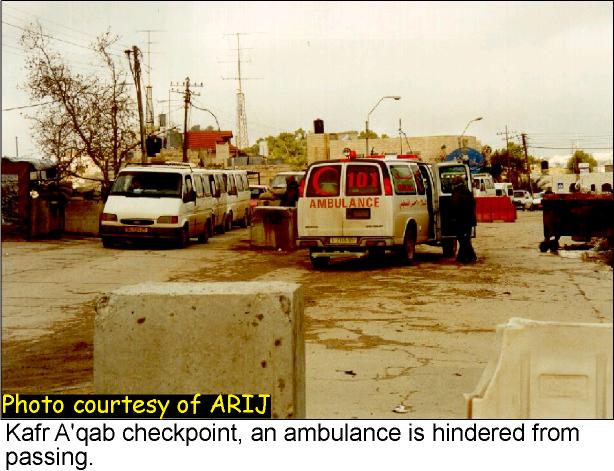

People have been forced to climb these blockades in order to move between towns and villages. Transport by vehicle has become largely impossible. There have been numerous examples of passengers being delayed or unable to reach emergency medical treatment. The human suffering has been exacerbated by the Israeli tank and helicopter bombardment of many Palestinian towns. The restrictions on movement have dealt a huge blow to the economy.

Between Ramallah and Birzeit March 2001

Near Ramallah's southern entrance January 2001

The main Palestinian cities have been surrounded by Israeli checkpoints and blockades and encircled by tanks. See Map 7 below for details of the blockade around Bethlehem as it stood in November 2000.

Map7: Roadblocks around Bethelehem

A similar pattern of blockading has been seen all across the West Bank and Gaza. The location of checkpoints and blockades in the West Bank in November 2000 can be found in Map 8. In addition, in January 2001, five checkpoints were moved from near the 1949 Armistice Line to locations deeper into the West Bank, effectively annexing settlements to Israel proper. Map 9 shows the location of those checkpoints that were moved in the northern part of the West Bank.

Map 8: Checkpoints and Roadblocks in the West Bank.

Map 9: Moving Checkpoints Eastwards.

A Recipe for a Lasting Peace

The ongoing fragmentation of Palestinian land and communities into disconnected cantons combined with the frequent collective punishment of closures, house demolitions, withdrawal of identification cards, the confiscation of private property and the military bombardment of the past few months impose a physically unsustainable situation.

A lasting peace can only be based on United Nations Resolutions 242 and 338, in which a fully sovereign Palestinian state will be established based on the Palestinian land occupied by Israel in 1967, neighboring a secure and independent Israeli state. A reciprocal, territorial exchange would be acceptable to the Palestinian Authority for particular cases. In this respect, the international community is required to secure such an outcome and only then can the currently stalled peace process be set back on track. More immediately, the international community is asked to intervene and lift the immediate hardships of the Palestinian people, imposed upon them by means of collective punishment.

The major challenges in Palestine at this stage are not a direct result of the content of the Oslo II Interim Agreement. Rather, they are a result of Israeli non-compliance with and partial implementation of the Agreement itself. A renewed commitment by Israel to the full and immediate implementation of the Agreement is absolutely necessary to restore Palestine's geographical integrity. By halting the confiscation of land and the expansion of Israeli settlements, by ceasing further construction of by-pass roads, by eliminating the restrictions on their use by Palestinians, opening roads and by pulling soldiers away from around Palestinian cities, Israel would not only begin to fulfill its obligation to a just and comprehensive settlement, but also demonstrate its foresight and wisdom by safeguarding the sustainable future of Palestine and its peoples.

In sum, regardless of the titles of the agreements to be signed between the Palestinian Authority and Israel, unless these agreements respect Palestinian rights that have been violated throughout the past 50 years, they will be unable to deliver a sustainable and lasting peace.

REFERENCES

-

ARIJ (Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem), GIS Database, 1999 and 2000

-

ARIJ Violations Records

-

BTSELEM House demolition reports

-

ICBS (Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics), Statistical Abstract of Israel 1999, No. 50 (Jerusalem, 1999)

-

Oslo II: Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and Gaza Strip, Washington (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Jerusalem, September, 1995)

-

PCBS (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics), The Census of Population and Establishments (Ramallah, Palestine: Palestinian National Authority, 1997)

-

PECDAR (Palestinian Economic Council for Development and Reconstruction), PECDAR Info: Monthly Information Bulletin, Vol. 1-2, No. 1-14 (October 1996- October 1998)

-

Wye River Memorandum, Washington (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Jerusalem, October, 1998)

Prepared by:

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem