Minefields in the West Bank

In 1998, the US State department estimated that there were around 260,000 landmines in Israel and the occupied territories, these include landmines laid by previous administrations. Israel is a non-signatory to the international Mine Ban Treaty that was drawn up as a result of the Ottawa Process, though Israel has declared a halt to AP (Anti-personnel) mine production.

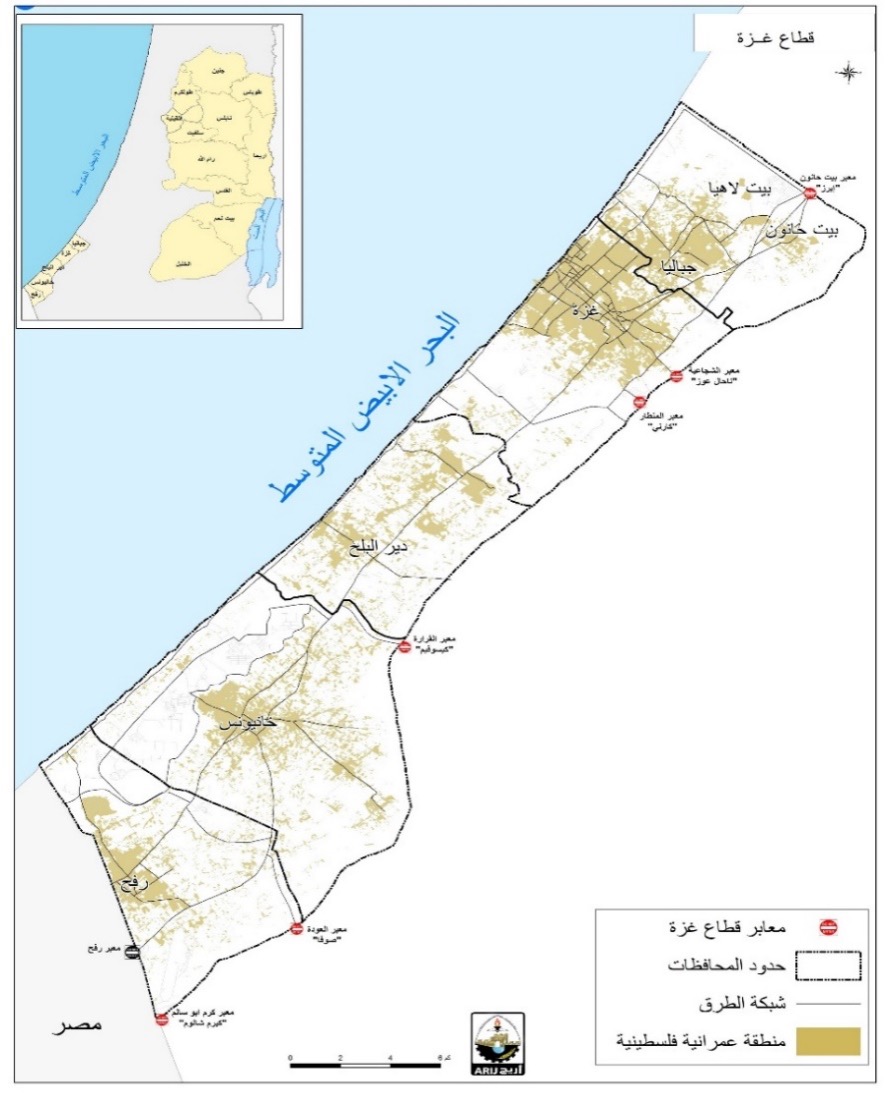

The exact number of minefields in Israel and the occupied territories is not known but in November 1999, the Israel State Comptroller issued a report which stated that 350 of Israel's minefields were no longer needed for security purposes For the West Bank, there is a joint map signed by both the Israeli government and the PNA, which locates the minefields declared by Israel in the West Bank; see map. However, at least four of the minefields marked on this map have been cleared, and there are certainly many fields unmarked on this map.

In July 1998, the Department of Field Security of the Israel Army set out its policy on the marking of minefields on maps saying 'minefields [that] constitute part of an obstacle laid by our forces on the front lines…there is no possibility of marking them on civilian maps. Regarding minefields that were laid by enemy forces…there is no impediment to marking them on the maps. Regarding minefields located in the vicinity of sensitive sites, such as electrical power stations, water pumps and the like, there is no impediment to marking them on the maps.' However, so far this remains only a principle and ARIJ has yet to come across any more complete maps.

Knowledge about the locations of minefields is essential for the Palestinian Authority to enable it to make informed decisions in the negotiating process, and in order to help in educating and informing the local populations. So far the issue of landmines ''has not been addressed in any of the agreements negotiated between Israel and the PNA. Failure on the part of the PNA to address this essential issue during the interim negotiation stage will give Israel an opportunity to deny all responsibility for landmines and UXO in the Occupied Territories.'

This project completes an initial step of verifying the status of the identified minefields and gathering information on the location of other minefields. Due to travel restrictions associated with entering closed military areas, in addition to the exceptional difficulties resulting from the current extended period of closure, fieldworkers have only been able to verify the locations in the south of the West Bank. The map above marks those minefields identified on the joint Israeli-Palestinian map for the West Bank, those verified by fieldwork are indicated, and those found to have been cleared are also marked.

Minefields not marked

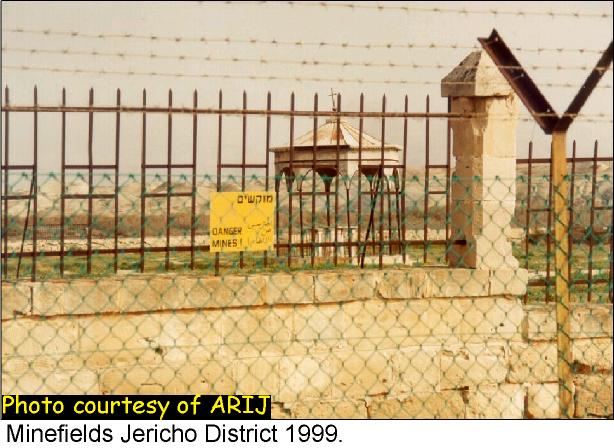

According to ARIJ fieldworkers, there is at least one minefield in Hebron district that is not marked on the map, located near the town of Halhoul, next to an Israeli military camp (see section on closed military training areas below). The existence of minefields in the Jordan valley and particularly along the Israeli-Jordanian border is well known as they can be seen clearly on the road to Amman. In 1997, Israel and Jordan completed a joint mine clearing project along their shared border. But fieldwork in 1999, revealed mined areas still remaining; see photo 1, photo 2.

Clearing Minefields

In January 1999, the division of Finances, Equipment, and Property in the Israeli Ministry of Defense stated that it was examining the possibility of the Israeli army evacuating unnecessary minefields, as well as adjacent areas suspected of being mined. However, cleaning operations of this kind are unfortunately not common. In spite of Israel's significant de-mining capabilities, villagers in the West Bank continue to suffer from the dangers of landmine fields laid by both the Israeli army and the previous Jordanian and British administrations.

In addition to offering its de-mining capabilities internationally, Israel has carried out some mine clearance of dubious quality within the West Bank. The first field to be cleared was Alnabi- Elias field near Qalqilya city. According to the Defense for Children International – Palestine Section (DCI/PS), a shepherd was killed who entered the area to graze his animals on the first day it was declared as cleaned by the Israelis. The Israelis also declared the minefield near Yaabad as cleared of mines. However, following an incident at the minefield on 15 July 1996, the Israeli side, replying to an inquiry from the Yaabad Municipality, stated (in a letter on 29 July) that:

[T]he minefield is very old. It has existed since the Jordanian period. We detected and removed the mines that we discovered. We cannot guarantee its emptiness because the detecting instruments cannot discover the mines if they are old. A heavy bulldozer crossed the minefield and exploded the mines. We hope you will notify us if anything is discovered.

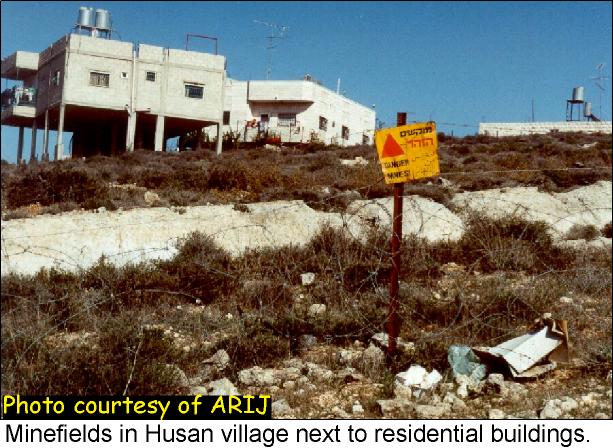

The case of Husan village provides a good example as to Israel's goals in mine clearance. This Palestinian village in Bethlehem District is located near to the 1949 Armistice Line. In 1985 a settlement was established very close to the built up area of the village, and later a bypass road was built to connect this settlement with Israel and with the main bypass route to Jerusalem. The road was designed to cross straight through the Jordanian minefield on the edge of Husan village. The Israeli Authorities went ahead and cleared the stretch of field that affected the road, but left untouched the areas on either side. One of the remaining mined areas lies close to a residential area of Husan; see photo. By clearing this minefield incompletely, Israel shows its ability to consider only its own interests and to ignore the needs of the local Palestinians. Presumably, the Israelis viewed this minefield as a useful means of providing security for the road.. By clearing this minefield incompletely, Israel shows its ability to consider only its own interests and to ignore the needs of the local Palestinians. Presumably, the Israelis viewed this minefield as a useful means of providing security for the road.

A more successful story is that of Surif village in Hebron District. At the entrance to Surif village, covering an area of not more than three dunums (0.3 hectares, 0.75 acres), there was a minefield laid by the Jordanian administration. The main road divides the area into two. Despite being surrounded by barbed wire, this field has caused the death and injury of many Surif villagers over the years. Finally, last year (2000) Israeli and Palestinian authorities cleaned the field with bulldozers, exploding the remaining mines. According to the villagers, the field is now clean, and the fence has been removed. Another cleared minefield is that at Sur Bahir village in Jerusalem District. This was located by fieldworkers and found to have been cleared around 15 years earlier. All that remains is the discarded warning sign; see photo.

Israeli Military Areas in the West Bank

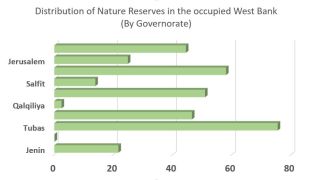

In March 1998 DCI/PS produced a report on victims of landmine and UXO (unexploded ordinances) explosions in the West Bank. They estimate that on average 84 people are injured annually by such explosions. Many of these injuries occur in or close to closed military areas. Currently 17.6% of the total land area of the West Bank is designated as closed military areas by the Israelis. These areas may or may not be mined, though many of the injuries are caused by discarded unexploded ammunition from training practices.

In August 2000, the Israeli human rights group B'tselem estimated that 36 people have been killed by discarded ammunition, including landmines, since 1987. The Palestinian human rights group LAW estimated the figure to be somewhat higher at around 54 victims, including 39 children. The summer of 2000 alone saw four Palestinian children killed by discarded ammunition. Two of these children (Khalil Yusef Abu 'Aram, 16, and Mu'en Atalahmeh, 13) died in Hebron District. Nassar Kabani, 15, died near his village Beit Dajan in Nablus District and Safwan A'si, 12, was killed close to his home in Beit Liqia (Ramallah District) adjacent to the 1949 Armistice Line.

Southeast of Yatta (Hebron District) near Jenba in Israel there is a military training area that covers hundreds of dunums of land straddling the 1949 Armistice Line. Military targets can be seen on hilltops in this area. The training activities can be seen and heard clearly from nearby Palestinian villages. These training activities take place on both sides of the 1949 Armistice Line. It was near this training area that Khalil Abu 'Aram, a boy from Yatta, was killed on 5th July 2000 by discarded ammunition. It is believed that this ammunition was intentionally placed outside of the training area.

Located west of Dura (Hebron District) inside Israel there is another military camp and training area. Ammunition from this military area, and missile training, have been responsible for the deaths and injuries of a number of villagers from Khirbet El Majd and nearby villages during previous years. Mu'en Atalahmehin was killed on 20th August 2000 by a grenade near his village Khirbet El Burj close to the military training area. The Israeli army responded that they would investigate the incident but stated, ''from initial examination there is no certainty that the grenade in question is in fact an IDF one''. However, the villagers are convinced the grenade was in fact linked to the attempt on the life of a Hamas activist who was expected to pass by the area. They cite the fact that the village children often played at that specific spot without previously suffering any injuries. In addition, the day before the incident, the Israeli army was seen training in the area. The villagers claim that this sequence of events is too suspicious to be dismissed as coincidence.

In response to a request as to the outcome of the Israeli army investigation into this incident, they stated that is was ''not possible to ascertain if the IDF [Israeli Army] is responsible for the presence of the grenade on the scene''. So, despite the fact that a child died because of discarded ammunition near one of the Israeli army training grounds, their investigation failed to provide any explanation for this terrible event, and seems to indicate a grave lack of care of the part of the Israeli army.

There is another Israeli army training camp in the same area, the Al Majnouneh camp, south of Dura village. Following the Sharm El Sheikh agreement, this camp has shrunk. The current area used for training is to the south of this camp and runs along the main road of the area. There is 30 dunums (3 hectares, 7.5 acres) of land west of the camp that was previously used for training, which is now left vacant. The area is surrounded by earth mounds to prevent access. The Israeli army's previous poor record of clean-up gives the locals good reason to suspect that this land remains unsafe because of discarded ammunition or landmines. An ARIJ fieldworker states that this area still contains landmines.

The two other children who died last summer, both lived in villages located on the edge of military training areas. The Israeli army claimed that one of these children Nassar Kabani wandered into a clearly marked firing-zone.

Fencing and Education

So long as minefields and military training areas remain in the West Bank, there are two important ingredients in preventing further injury and death: fencing of the areas and education of local residents. The Israeli State Comptroller 1999 report found some minefields that were not properly marked and fenced. The report also stated that the cumulative perimeter of the areas suspected of being mined within the 'Southern Command region' was about 350 kilometers, so it is claimed that proper fencing is impossible. This is said despite the fact that inadequate fencing leaves the local population at risk from injury and death. It is worth comparing this with the fact that the Israeli authorities have been willing to consider erecting a 90km high-security fence along parts of the West Bank border.

As for education, since 1996, Israel's Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been engaged in mine clearance and mine awareness operations in Angola. An Israeli NGO, Aid Without Borders has also been active in Kosovo where it taught mine awareness to children in conjunction with the British Mines Advisory Group. However, these groups do not provide their services in the West Bank. The DCI/PS has initiated an education program after the results of their 1998 survey (of 334 explosions) indicated that a low level of awareness was a significant factor leading to explosions. In particular the 1998 survey indicated that the victims of these explosions tend to have lower levels of schooling than the general population. Important as such an approach is, it remains only a temporary solution to the long-term issue of the presence of military zones in the West Bank.

Conclusion

Local people will continue to be injured and even killed by landmines and UXOs if the practices of the Israeli army are not altered. In addition to the issues of poor fencing and marking, the Israeli army fails to properly investigate incidents of injury and death near their training grounds. The heart of the issue is that Israeli army training areas should be removed from the Palestinian West Bank. Until that happens, they should be clearly marked and fenced and all incidents should be investigated and should result in recommendations for changes in procedure.

The Israeli army has shown disregard for the safety of local population by continuing to train near residential areas, without effective mechanisms in place to prevent locals being injured by discarded ammunition. On half of the known incidents of mine clearing in the West Bank, the clearing has been carried out at levels below internationally accepted standards for humanitarian clearing, leading to further injuries and deaths. Due the unwillingness of the Israeli army to take actions to protect the civilians around their imposed military areas, it is essential that Palestinians children be taught the dangers of touching or approaching discarded ammunition. An awareness campaign is needed in order to help protect Palestinian children from the negligence and disregard of the Israeli army, and will remain necessary until the training areas and minefields are removed from the West Bank.

Finally, more information is needed on the location of landmines in order to allow for affective planning and negotiations by the Palestinians. The process of gathering details of sites needs to continue until a full picture of the extent of the problem is produced.

References:-

1. Perhaps as many as half of these are in area of Southern Lebanon that Israel withdrew from in May 2000.

2. Israeli State Comptroller's Report 1999, 50a

3. Quoted in the Israeli State Comptroller's Report, 1999.

4. Fihmi Shahin, 'Yesterday's War Harvests More Victim's Today,'' Haquq al-Nas (People's Rights magazine), LAW, the Palestinian Society for the Protection of Human Rights and the Environment. August 1999, No. 30, p. 13.

A letter from the IDF to the Yaabad municipality on 29 July 1996

Prepared by:

The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem